Depression In Pregnancy? rTMS Might Be Our Most Safe Treatment

A Sunday Morning Review of the evidence for the treatment of depression in women who are pregnant.

As a parent of twins, I am here to tell you: pregnancy is terrifying. It is, of course, beautiful and might go fine. However, not all pregnancies are smooth sailing. Having another life gestate while exquisitely vulnerable to biological insults that could change the entire course of their life after birth? That is a huge deal. The whole situation can get substantially more dicey when there is depression involved. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is estimated to affect between 7% and 12% of pregnant women worldwide.1

First, a Marketing aside: I have a live-action event coming up! It’s called RAMHT ‘25 LA!

It is on May 18th, in Los Angeles! Get more info here.

To begin, depression itself can be harmful to a developing baby, as my colleague and sometimes co-author Justin Chan2 highlights:

Babies born to women with untreated depression are at risk of prematurity, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction.2,3 The negative consequences of untreated maternal depression might also affect childhood development. Higher impulsivity, maladaptive social interactions, and cognitive, behavioural, and emotional difficulties have been shown to occur.4,5

This is all in addition to the harm to the mother, who will also be suffering from depression while worrying that the depression will be a problem for her baby. These risks are not trival, as Chan et. al. note:

Importantly, pregnant women with depression are more at risk of developing postpartum depression and suicidality.6 Increased hospital admissions and pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia have also been linked to untreated maternal depression.6,7

Oral medicines to treat depression can present dangers during pregnancy, too. The first risk people worry about is major birth defects, and that risk has been assessed in large samples, such as this paper published in JAMA in 2020:

In this case-control study of 30 630 mothers of infants with birth defects and 11 478 control mothers, there were previous and new associations between individual selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, venlafaxine, and bupropion and specific birth defects…Venlafaxine was associated with more birth defects than other antidepressants, which needs confirmation; studies to assess birth defect risk among women taking antidepressants should account for the underlying condition.3

Of note, other antidepressants also led to additional birth defect risk if there were predisposing risk factors in place as well.

There are risks beyond birth defects, as well. Pregnancy-induced hypertension, with risks for mother and child, is increased in a case-control study from Canada:

use of antidepressants during pregnancy was significantly associated with increased risk of pregnancy-induced hypertension (OR 1.53, 95% CI 1.01, 2.33). In stratified analyses, use of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.00, 2.55), and more specifically, paroxetine (OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.02, 3.23) was associated with risk of pregnancy-induced hypertension.4

The risk of pre-term birth and low birthweight were both increased in a large sample published in JAMA Psychiatry as well:

Gestational age and preterm delivery were statistically significantly associated with antidepressant exposure (mean difference [MD] [weeks], −0.45; 95% CI, −0.64 to −0.25; P < .001; and OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.38 to 1.74; P < .001, respectively), regardless of whether the comparison group consisted of all unexposed mothers or only depressed mothers without antidepressant exposure. Antidepressant exposure during pregnancy was significantly associated with lower birth weight (MD [grams], −74; 95% CI, −117 to −31; P = .001);5

I could go on and address the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn, but you already get the point. The dangers of depression are high, and the risk of oral antidepressants are real and present. However, given the problem and the treatment both have risks, there is a real “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” quality if we assume we can never reduce the risk of depression without using a potentially toxic drug.

What we would benefit from is a different way to treat depression that is both more effective and safer for people who are pregnant and their soon-to-be kiddos.

New data suggests neuromodulation with transcranial magnetic stimulation is one such option. I know my readers are simply shocked—SHOCKED—that in this newsletter, crafted lovingly by a doctor who has treated thousands with TMS, we would suggest such a thing.

It’s not like I have a bias toward thinking brain stimulation is a good idea, as evidenced by the following brain stimulation-themed articles…

Those articles are just a small sampling of my voluminous output on the topic….not to mention an entire book—Inessential Pharmacology. (Amazon link) on the topic of drugs sucking. I have a bias; yes, I admit it!

However, new data backs this up. It’s not just me.

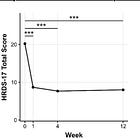

In the February 2025 issue of the Journal Brain and Behavior, Angeline et. al. penned:

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Pregnancy: Efficacy, Safety, and Future Implications for Perinatal Mental Health Care

The authors did a systematic review of 363 publications, of which 3 met inclusion criteria for their review, only focusing on women who were pregnant at the time and had major depressive disorder. The first thing to point out, for my readers, is that only three papers on the topic were available. There are TOO FEW STUDIES on a crucial issue for women and, subsequently, all humans.