Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) Should Be Covered by Medicaid: An Argument

An economic argument for all my colleagues talking to plan administrators

The Frontier Psychiatrists is a daily health-themed newsletter. This article was going to start as an email to my colleague, Olu Ajilore, M.D. Like most of my colleagues, we originally met on Clubhouse. I’m Owen Muir, M.D., DFAACAP. I’ve been treating patients with TMS treatment since 2017 in my practice, Fermata. I also work at Acacia Clinics in Sunnyvale, CA. I cofounded a company to make the deployment of breakthrough treatments easier, with Breakthrough6. I have a vested interest, and what follows is a detailed explanation of why, in terms of efficacy and cost-effectiveness.

Medicaid plans face a difficulty—which is true of all health plans, but it is particularly true of state Medicaid plans. They don't have infinite money. Medicaid is the health insurance for people who are poor. I wish there were a better way to put it. Medicare and Medicaid were created with a compromise. Medicare, which covers predominantly the care of the elderly, would be covered at the federal level. Medicaid, which covers payment for healthcare for people, without commercial health insurance, who are predominantly poor, would be handled on a state-by-state basis.

I don't think it's a complicated argument to explain that some states have more money, and some states have less money. That money, on a state-by-state basis, needs to be used to cover the care of people who don't have commercial health insurance because they don't have a job. Some states have more of these individuals, and some states have less.

The rate for Medicare reimbursement was set at the federal level, but each state can choose how much they pay for their Medicaid population, and it's almost always less than the Medicare rate. Much of the source of healthcare access disparities in America began here, in 1965, with this compromise.

To be explicit: this was a racist compromise from the start. Wealthy, white people who were old wanted to make sure their health insurance would cover their care. Individual states, many in the south with poor and minority populations, not to beat around the bush, had poor black populations, and wanted the ability to pay less for their healthcare if they chose. And to get Medicare passed, Medicaid had to be a state-by-state choice.

Medicaid is our modern “3/5 compromise.”

That was how it was born, I'm not saying it's administered in a way that is intended to be racist at this time. I am saying there is an inequity built into the system, to this day.

One of the things that is true about Medicaid plans, that is not true about Medicare, is that people don't stop being old all of a sudden. Once you start being eligible for Medicare, you continue being eligible for Medicare. Because Medicare is for people who don't stop being old. Medicaid does not have the same stability. Sometimes you get a job, and get commercial insurance, and you are no longer on the same health plan anymore. 100% of people who get commercial health insurance because they got an awesome job stop being on their Medicaid plan.

This means that the time anybody sends in a Medicaid plan, on average, is less than the time they spend on other plans. And this is the fundamental glitch in the matrix. Medicaid plans have, on average, only 10 months to manage the health of any individual. After this time, they either get a job or switch to a new Medicaid plan.

It's tough to manage population health when you only have months to accomplish the goal:

We also found that Medicaid and CHIP beneficiaries were enrolled for an average of 11.6 months over a 12-month enrollment span

You have to choose what to pay for, and what not to pay for if you're a plant administrator of a state Medicaid plan. But you can't do anything that's going to get people well. Because almost nothing gets people well in an average of 10 months.

We have data that demonstrate psychiatric interventions that work rapidly might provide the most robust savings for the economics of Medicaid.

Dual-eligible participants—those are individuals with both serious disabilities, so they qualify for Medicare through the Social Security disability program, with Medicaid as secondary insurance, who might be the best suited for rapid-acting mental health treatments.

Transcranial, magnetic stimulation is that treatment, today.

There's nothing we can do about the unfortunate origins of Medicaid, and we can't waive a wand and make American healthcare cost less overnight. We can't put more money into state coffers to cover healthcare magically. Absent single-payer healthcare at the federal level, and massive reforms, these plan administrators have to work with the cards they are dealt.

A crucial task is determining who's going to stay in a plan, and who's not. I would argue that dual-eligible recipients of Medicaid funds, those who were both disabled and can't work because of it, might be the least likely to change plans.1

Given the economics of Medicaid, every healthcare expense is taking a match, and burning money, unless it generates savings in a very short time frame to be cost-effective. TMS works exactly this way.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation gets treatment-resistant depression to remission.

It does this reliably, in massive data sets. For example with dTMS, in 1753 patients at 21 sites:

30 sessions of Deep TMS led to 81.6% response and 65.3% remission rate.

20 sessions led to 73.6% response and 58.1% remission rate.

iTBS led to 72.4% response and 69.2% remission.2

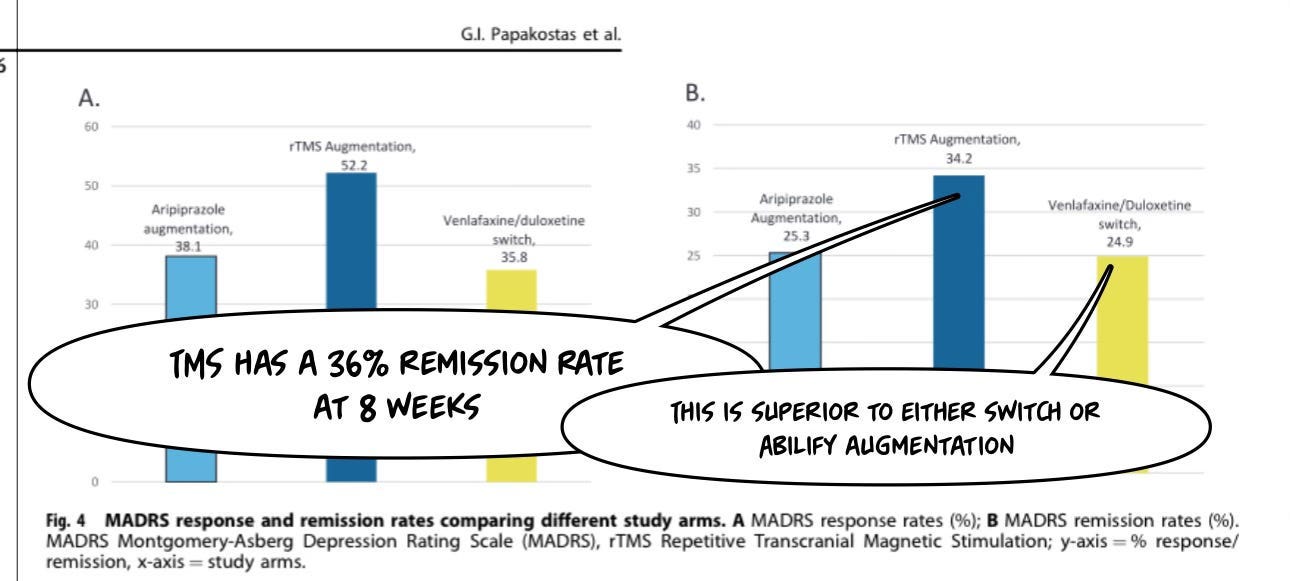

It is better, in ASCERTAIN-TRD, a well-designed 2024 published RCT, than all other augmentation strategies assessed:3

Accelerated TMS approaches have FDA approval with the SAINT system. Reviews of all available data in 2024 also agree.4

These accelerated approaches (using shorter and more effective iTBS protocols) are also cost-effective:

From a healthcare system perspective, the average cost per patient was USD$1,108 (SD 166) for a course of iTBS and $1,844 (SD 304) for 10Hz rTMS, with an incremental net savings of $735 (95% CI 688 to 783).

The average cost per remission was $3,695 (SD 552) for iTBS and $6,146 (SD 1,015) for 10Hz rTMS, with an average incremental net savings of $2,451 (95% CI 2,293 to 2,610).5

It is Wildly Cost-Effective

In the world of “cost-effectiveness” research, we love a Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY) as a metric, like the deserts love the rain. I’ll define that standard, for general audiences:

the change in utility value induced by the treatment is multiplied by the duration of the treatment effect to provide the number of QALYs gained.

A “change in utility value” is an awkward way of saying “how much better a treatment gets you.” Speed makes people feel good. It doesn’t last very long. Not a leader in improving QALYs. Knee surgery improves your ability to walk, and tends to last longer than one dose of a medicine. You get the idea.

Cost-effectiveness research has been supportive of TMS in the treatment of depression (in 2009):

Compared with sham treatment and at a cost of US$300 per treatment session, TMS provides an ICER of US$34,999 per QALY, which is less than the “willingness-to-pay” standard of US$50,000 per QALY for a new treatment for major depression.

When productivity gains due to clinical recovery were included, the ICER was reduced to US$6667 per QALY. In open-label conditions, TMS provided a net cost saving of US$1123 per QALY when compared with the current standard of care.6

In a 2015 assessment by researchers in Australia, those results were replicated versus pharmacotherapy:

Compared with pharmacotherapy, rTMS is a dominant/cost-effective alternative for patients with treatment-resistant depressive disorder. The model predicted that QALYs gained with rTMS were higher than those gained with antidepressant medications (1.25 vs. 1.18 QALYs) while costs were slightly less (AU $31,003 vs. AU $31,190). In the Australian context, at the willingness-to-pay threshold of AU $50,000 per QALY gain, the probability that rTMS was cost-effective was 73%.7

TMS was compared to pharmacotherapy in patients who had only failed one medication trial (as opposed to two in the above studies), and the results replicated with greater benefit in younger patients (aka Medicaid v. Medicare) patients:

Lifetime direct treatment costs, and QALYs identified rTMS as the dominant therapy compared to antidepressant medications (i.e., lower costs with better outcomes) in all age ranges, with costs/improved QALYs ranging from $2,952/0.32 (older patients) to $11,140/0.43 (younger patients)…rTMS was identified as the dominant therapy compared to antidepressant medication trials over the life of the patient across the lifespan of adults with MDD, given current costs of treatment. 8

When comparing traditional once-a-day TMS to ECT, it’s less cost-effective—but the authors note that TMS is lower in side effects and more preferable, which I have found to be the case in severe depression:

However, ECT patients reported a higher percentage of side effects (P<0.01) and the TMS treatment scored better in terms of patient preference. The cost benefit of ECT was higher than that of TMS (US$2075 vs US$814). Patient’s preferences for treatment could be more intense in the TMS, if the TMS is included in the Health Maintenance Organization’s service list.

These cost-effectiveness results were replicated in Singapore.9 They have been replicated in dTMS for OCD.10 The results have been replicated in Europe in 2022.11 Leaders in the field agree, as does the professional society—CTMSS—and multiple Medicare MOCs.12

It’s hard to imagine more cost-effectiveness consensus— worldwide— than TMS has at this point.

The time for Medicaid coverage, given cost-effective remission is happening on the time scale of a week to a month, is now.

Thanks for reading, and if you run a Medicaid Plan, I thank you for your coverage policy changes in advance!

Lipson, D., Kimmey, L., Chelminsky, D., Margiotta, C., Tourtellotte, A., & Lakhmani, E. W. (2021). Why dually eligible beneficiaries stay or leave integrated care plans (No. da9ea9f4e07a4ef3bd4da46ee4bddd38). Mathematica Policy Research.

Tendler, A., Goerigk, S., Zibman, S., Ouaknine, S., Harmelech, T., Pell, G. S., Zangen, A., Harvey, S. A., Grammer, G., Stehberg, J., Adefolarin, O., Muir, O., MacMillan, C., Ghelber, D., Duffy, W., Mania, I., Faruqui, Z., Munasifi, F., Antin, T., . . . Roth, Y. (2023). Deep TMS H1 Coil treatment for depression: Results from a large post marketing data analysis. Psychiatry Research, 324, 115179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115179

Papakostas, G. I., Trivedi, M. H., Shelton, R. C., Iosifescu, D. V., Thase, M. E., Jha, M. K., Mathew, S. J., DeBattista, C., Dokucu, M. E., Currier, G. W., McCall, W. V., Modirrousta, M., Macaluso, M., Bystritsky, A., Rodriguez, F. V., Nelson, E. B., Yeung, A. S., Feeney, A., MacGregor, L. C., . . . Fava, M. (2024). Comparative effectiveness research trial for antidepressant incomplete and non-responders with treatment resistant depression (ASCERTAIN-TRD) a randomized clinical trial. Molecular Psychiatry, 1-9.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-024-02468-x

Van Rooij, S. J., Arulpragasam, A. R., McDonald, W. M., & Philip, N. S. (2024). Accelerated TMS - moving quickly into the future of depression treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology, 49(1), 128-137. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-023-01599-z

Mendlowitz, A. B., Shanbour, A., Downar, J., Vila-Rodriguez, F., Daskalakis, Z. J., Isaranuwatchai, W., & Blumberger, D. M. (2019). Implementation of intermittent theta burst stimulation compared to conventional repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with treatment resistant depression: A cost analysis. PLOS ONE, 14(9), e0222546.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222546

Voigt, J., Carpenter, L., & Leuchter, A. (2017). Cost effectiveness analysis comparing repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation to antidepressant medications after a first treatment failure for major depressive disorder in newly diagnosed patients–A lifetime analysis. PLoS One, 12(10), e0186950.

Zhao, Y. J., Tor, P. C., Khoo, A. L., Teng, M., Lim, B. P., & Mok, Y. M. (2018). Cost-effectiveness modeling of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation compared to electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant depression in Singapore. Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface, 21(4), 376-382.

Zemplényi, A., Józwiak-Hagymásy, J., Kovács, S., Erdősi, D., Boncz, I., Tényi, T., ... & Voros, V. (2022). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation may be a cost-effective alternative to antidepressant therapy after two treatment failures in patients with major depressive disorder. BMC psychiatry, 22(1), 437

Weissman, C. R., Bermudes, R. A., Voigt, J., Liston, C., Williams, N., Blumberger, D. M., ... & Daskalakis, Z. J. (2023). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: Mismatch of evidence and insurance coverage policies in the United States. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 84(3), 46813.

How long does remission last for those who benefit from TMS? If it’s not permanent, wouldn’t future additional tx need to be calculated in? If periodic ‘touch ups’ are needed, does their effectiveness for the patient change over time? or in other words, could it cost more over time? This article doesn’t provide the level of detail needed to predict real costs, which could be more persuasive to plan administrators. They are, after all, business people who depend on numbers.