Rapid Treatment of Bipolar Depression with Accelerated TMS: Third Time's the Charm?

A third RCT, from independent authors, further establishes the inability of authors to craft an appropriate treatment resistant Bipolar depression Study. Also, aTMS works.

As a psychiatrist, bipolar depression is historically one of the more difficult problems for me to address for my patients. As a patient with bipolar disorder, bipolar depression was the scourge of my early life. About a decade ago, my bipolar depression was treated with transcranial magnetic stimulation by a pioneer doctor, here in New York. His name is Robert MacMullen, M.D., and he is a good physician. He's also a good man. He ran his practice for the benefit of his patients—sometimes to the detriment of financials, as so many of us do. There was not an FDA approval for TMS in bipolar depression then, and there still isn't now.

Today's article is about the third randomized control trial in the past couple of months, this time from Applebaum, et. al. at UCSD.1

Ironically, UCSD is also a school that can be (allegedly) pretty awful to its medical students with bipolar disorder. That's a story for another time, but I look forward to being able to tell it. It's not my story to tell, not entirely.

I wrote about a prior publication on TMS in bipolar depression. I also covered the first publication on iTBS in Bipolar Depression here. This is the third similarly designed trial. Yes, there will be criticisms.

Before I dig into the small “randomized” controlled trial, I want to give some overview so my readers understand how important it is to develop novel bipolar depression treatments. The standard of care is substandard.

Bipolar disorder is not a name I like. The original name for this disorder was manic depressive illness, which I considered more descriptive and accurate. Bipolar disorder came into vogue with the creation of DSM III. I suspect a lot of it had to do with a Pharma agenda swirling around psychiatry to get a new medication, Depakote, successfully to market. Historically, lithium was considered the gold standard of treatment for bipolar, and it still is. Lithium leads to less death by suicide, longer life, and less cycle frequency over time. If you're lucky enough to be a lithium responder, that's awesome.

It also has a bunch of intolerable side effects, causes one to drink a lot and pee a lot, and maybe even have a hand tremor all the time. It might ruin your kidneys. It might ruin your thyroid. It might ruin your ability to have an erection for male humans. It may or may not make you gain weight; it has many problems. It requires blood draws. It requires careful monitoring. It's a real medicine that requires real doctors, nurses, and other diligent health professionals to monitor it. Here is a 5 part guide on lithium monitoring from my friend and contributor to The Frontier Psychiatrists,

: Part 1. Part 2. Part 3. Part 4. Part 5.One thing lithium doesn't do? Treat bipolar depression. Ironically, it leads to less bipolar depression over time, but it's not an acute treatment. If you're feeling depressed now, time is the most likely thing to heal your depression. If you're taking lithium, there is good data that lithium itself will make your depression better.

People with bipolar depression can look a lot like people with other depression. It can be hard to differentiate the two. This is extra true if it takes a while in your life for mania to present. Then, someone has to be around to notice its mania. Then, that needs to lead to an accurate diagnosis.

My friend Lila recently wrote about her discovery that she had bipolar disorder, to which I had a front row seat. Most of the time people with bipolar are unwell is time spent depressed. Mania, for most people, is a defining feature but not the star of the show over the long expanse of one’s life.

The other options for bipolar depression, by and large, are antipsychotic medications. If you want one takeaway from this article?

Drugs called antidepressants don't treat bipolar disorder’s depression.

Drugs like olanzapine-fluoxetine combination, quetiapine, cariprazine, lurasidone, and lumateperone tend to cause weight gain and also don't work phenomenally well. Effect sizes are in the 0.5 range. There are an array of other side effects, including tremors, dystonia, and even permanent Tardive Dyskinesia. Want to read more about those drugs? I wrote a whole book about them—Inessential Pharmacology (affiliate link on Amazon).

None of the treatments work amazingly well, and virtually none of them have good evidence for “treatment-resistant” bipolar depression. That is to say, if those treatments don't work, we don't have much. We have electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), but it's hard to access and scary, and still not that fast. It takes around 12 sessions, three times a week, over the course of about a month to get that treatment.

So, a treatment that works in five days would be fantastic. Now, here's a third randomized control trial demonstrating that it's possible, but it’s not without its problems.

This protocol used fMRI plus a pattern of a simulation called intermittent theta burst stimulation, or iTBS. Astute long-time readers will recognize I’ve been writing, recording, podcast appearing, and publishing—about accelerated protocols in major depressive disorder and even writing up case series using accelerated iTBS in bipolar dating back to 2018.2

The newsletter has one love—and that is Table One. However, it is in an open relationship with data on accelerated TMS, and other interventional and drug-free treatments. It’s like breaking news about data polycule?

Yes, that is Leon humor.

Now, to this new paper!

It did a thing I found annoying, and then another thing I found annoying. They dropped all the crucial details into supplemental materials. I had to dig to see how flawed this paper was. In the supplemental materials, they note the inclusion criteria:

Patients diagnosed with Bipolar I or Bipolar II Disorder, between 18 and 70 years of age in a current depressive episode were eligible for this study.

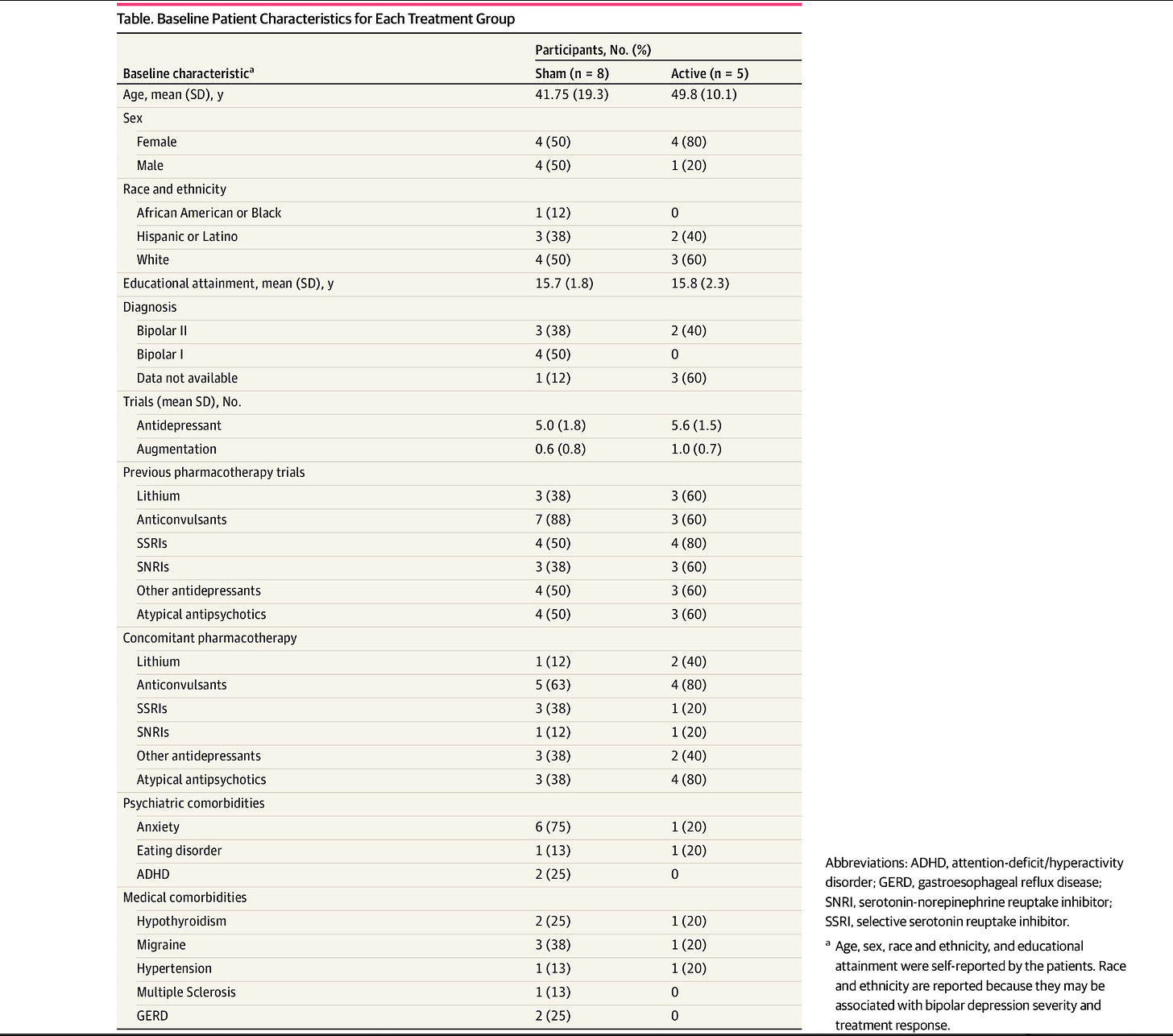

Nothing to see here. Except…the randomization failed…the ages are very different and the sex assignment is very different between groups.

The sham group had a mean age of 41.75 years (SD = 19.3), while the active group had a mean age of 49.8 years (SD = 10.1). In the sham group, four participants were female and four were male, compared to four females and one male in the active group.

The active group was, on average, 10 years older than the sham group. Are there biological differences in people a decade older? There were gender differences, which is similarly problematic. Are there differences between men and women? How about between pre and post-menopausal women—given the crucial age difference between groups? They subsequently explain:

Treatment assignment was not equal because randomization was done listwise and the full planned allotment was not achieved because the period of funding ended, leading to an unbalanced sample.

They also selected—like the prior irksome papers on the topic—a completely useless “treatment-resistant bipolar depression” standard. They chose treatment resistance on the ATHF:

Participants were required to have treatment-resistant depression (i.e., having undergone two or more prior antidepressant trials that have failed to produce a response, as defined by the Anti-Depressant Treatment History Form),

This form asks about antidepressants. Ya know, the medicines that I already pointed out, with NIH-funded references, don’t ever work in bipolar depression? Why would we use drugs that don’t work as a standard for treatment resistance? I am also resistant to pixie dust and rainbows to be able to fly, but neither of those would be expected to give me wings, would they now? It’s like writing a paper on “Treatment-resistant HSV infection” when the only medicine tried was penicillin.

These patients were mismanaged for their bipolar disorder:

The sham group had an average of five prior antidepressant treatment trials (SD = 1.8), while the active group averaged 5.6 trials (SD = 1.5). Participants in the sham group had an average of 0.6 augmentation trials (SD = 0.8), compared to one trial (SD = 0.7) in the active group.

This is a profoundly unserious inclusion criterion, and I will continue to think less of every author who uses this misleading standard. Further, I continue to be skeptical—either these patients had bipolar disorder…or they had unipolar depression and lied about having bipolar disorder in the past to get SAINT for free (maybe). At least, for plausibility, a plurality had a history of lithium treatment:

At the time of screening, three participants in the sham group and three participants in the active group had a history of treatment with Lithium. Additionally, seven participants in the sham group and three participants in the active group had a history of anticonvulsant treatment.

As promised, table one:

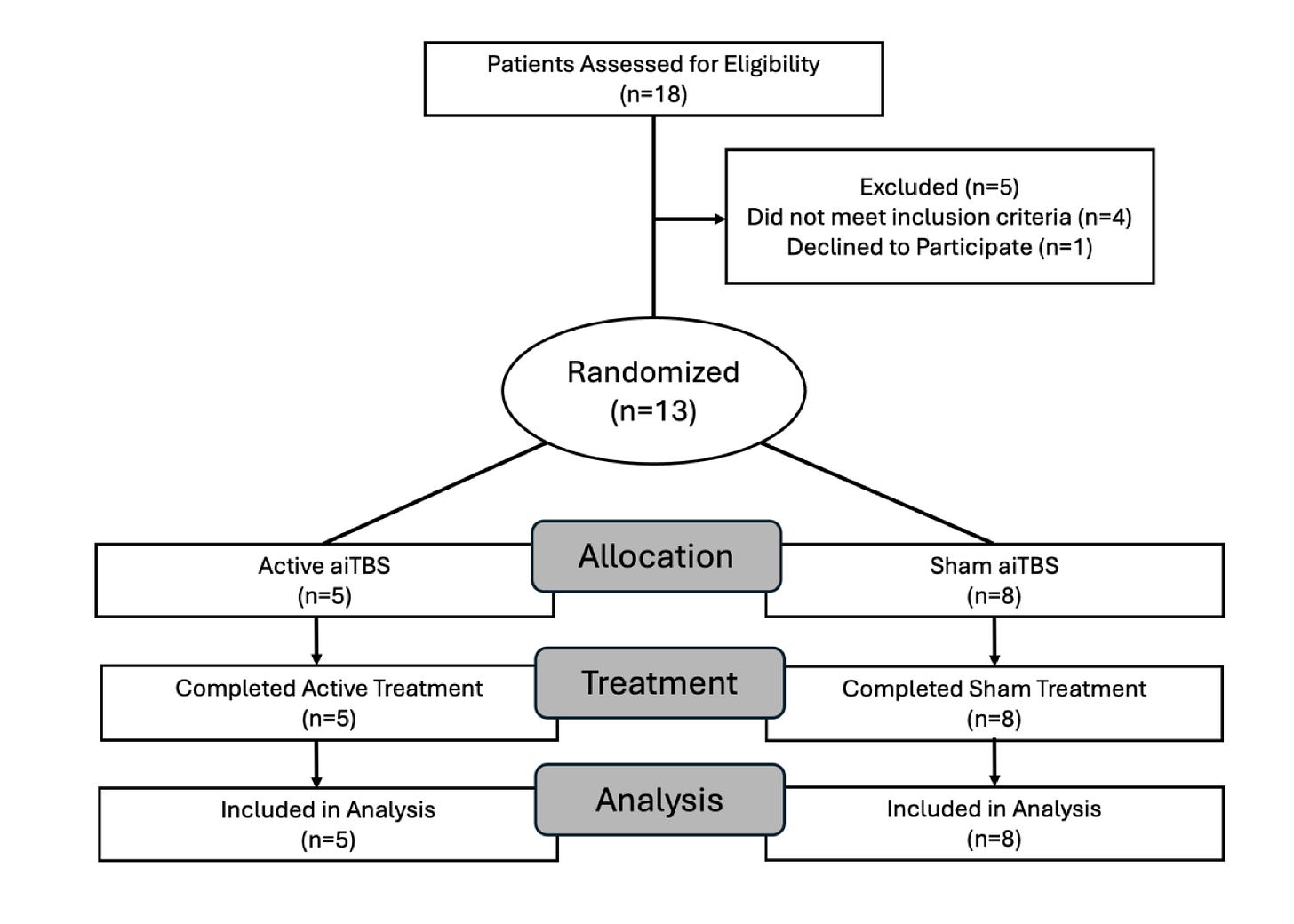

Now, the CONSORT diagram (which tells us how patients flow through a trial):

So, in this third attempt at such a paper,… a deep breath. A non-successfully randomized trial of maybe bipolar disorder, aiTBS, worked wonderfully. Sham did not:

The imaging was collected on an appropriate device, with what I suspect to be slightly short interval scans (I’m used to 8 minutes per sequence). Still, I doubt this is of methodological importance:

Scanning was conducted using a Siemens 3T Magnetom Prisma Fit scanner with a 64-channel head coil (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) at the University of California, San Diego. Each session included the acquisition of 20 minutes of BOLD resting-state fMRI data (gradient-echo EPI, 2 mm isotropic resolution, 52° flip angle, TR/TE = 37/800 ms) along with field maps for distortion correction. These were collected in four individual, 5-minute scans, two with anterior-posterior orientations and two with posterior-anterior orientations.

I present that information not because the average reader can make heads or tails of it. Instead, it’s to point out that….

1. MRI is as close to magic as you can find on earth.

2. These scanners aren’t your community hospital's standard 1.5 T MRI machine. As described in this paper, this is not yet a scalable or accessible treatment.

The targeting methodology did not use Magnus Medical’s SAINT (registered trademark) algorithm—it used an approach based on work by (the magnificent) Robin Cash:

The individualized stimulation target in the left dlPFC for each participant was identified based on their baseline resting-state scans. The target location was determined using the cluster-based approach described by Cash and colleagues3, which identifies regions within a dlPFC mask that exhibit the strongest negative correlation with the sgACC. The sgACC signal was defined using the seed map methodology, and a subset of the most negatively correlated, spatially clustered voxels was selected. The center of gravity of the largest voxel cluster was then designated as the stimulation target coordinate.

This is the same brain region targeted SAINT— the sub-genual cingulate (sgACC).

After ripping on this paper for a while, I will also give them kudos: the authors did e-field modeling of their approach so they could overlay the expected effect of the brain stimulator with their expected target. Again, this is not supposed to be comprehensible to the lay reader—or even the expert scientist in almost any other field. I want readers to have a sense of how wildly complicated this science is and what a marvel we are witnessing when we can use the magnetic fields that protect our earth from interstellar radiation to rescue people suffering from crippling bipolar depression. It’s a miracle wrapped in 100 years of diligent work by dedicated scientists:

Electric-field (e-field) modeling was used to improve and optimize the target by personalizing the coil orientation and maximizing the e-field amplitude at the stimulation site for each patient. This process accounted for changes in electrical conductivity between cerebrospinal fluid, gray matter, and white matter, as well as variations in the subject's dlPFC gyral shape and orientation, which influence current distribution depending on coil positioning.

Just wow. Also, I promise this is among the correct ways of doing it.

For additional Kudos, the blinding efforts in these trials are among the best in science:

The sham treatment delivered an identical stimulation protocol but with the shielded side of the coil towards the participant. Somatosensory matched sham stimulation was achieved by placing two electrodes on the left side of the forehead under the coil for all patients. Electrical stimulation, scaled to the magnetic stimulator output intensity, was delivered synchronously with the sham magnetic pulses to mimic the sensation of magnetic stimulation. To assess blinding, patients were asked to guess the treatment allocation following the first and last treatment session.

I once asked Mark George, M.D., the inventor of therapeutic TMS, how good the blind was using this system of electrodes that zap you. He responded reassuringly, “I can’t even tell the difference.”

This is a paper that demonstrates…again…that in a clinical trial, SAINT works for depression symptoms. It’s up for debate (in my mind) how well any of these “treatment-resistant bipolar depression” samples have been characterized. Using the ATHF is the WRONG answer, according to me.

Bipolar depression is a terrible problem. We need to appropriately fund research. We also need to demand seriousness in terms of understanding our study subjects. This has long been a problem in bipolar disorder research and needs to get more serious more quickly. Lives are on the line. Not the least of which, at one point in my life, was mine.

Appelbaum LG, Daniels H, Lochhead L, et al. Accelerated Intermittent Theta-Burst Stimulation for Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Depression: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(2):e2459361. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.59361

Treatment of mixed mania and depression using bilateral intermittent theta burst: Case series Muir, Owen et al. Brain Stimulation: Basic, Translational, and Clinical Research in Neuromodulation, Volume 11, Issue 6, e14.

Cash RFH, Cocchi L, Lv J, Wu Y, Fitzgerald PB, Zalesky A. Personalized connectivity-guided DLPFC-TMS for depression: Advancing computational feasibility, precision and reproducibility. Hum BrainMapp. 2021;42(13):4155-4172.

I finished reading this entire piece. Great stuff. Who else can say that? Might you post a link to your Ampa piece? Thanks.