Seroquel I: Schizophrenia

Start with, Switch to, Stay on...this newsletter, for articles about medicines

The Frontier Psychiatrists is a very successful newsletter among you, the very tiny niche of people who love reading about the heady admixture of regulation, clinical data, and humor. I also don’t want to disappoint any of you—thus this next “in the pocket” article.

For those new to TFPs, when I decided to bail on oral medicines, as a psychiatrist, I started writing what has become quite the series on what I learned about medicines. To be very clear—I’m not into them. In my clinical practice, I’m focusing on Rapid Acting Mental Health Treatments— this includes Fermata, in Brooklyn, and at Acacia Clinics in Sunnyvale, CA.

I am also hosting a real-life conference on the topic—RAMHT NYC 2024—on May 5th.

However, in the process of forsaking small molecule drugs, I decided a guide to the world of psychopharmacology I’m leaving would be helpful. What started happening is I found out that there's more than I can write about one day, and so that one drug ends up taking up a bunch of days! Today, Seroquel and schizophrenia as a monotherapy, but I hope all set up some of the other concerns additional articles will address… foreshadowing!

Seroquel (quetiapine)

According to the FDA, is an “atypical antipsychotic indicated for the treatment of:

Schizophrenia

Bipolar I disorder manic episodes

Bipolar disorder, depressive episodes

This includes approval for use in children 10-17 as monotherapy in bipolar mania.”

One of the strange things about having written this series of reviews is how much I learned in the process. None of it has been enough to convince me that my “I am not bothering with these drugs anymore” strategy that started the journey is the wrong one. However, I sometimes find my presuppositions challenged. I’m going to state my presumptions up top, and then do my deep dive, and we can see, together, if my impressions are supported by the evidence.

I think…a priori:

Seroquel is an effective treatment for bipolar depression and mania, but it might be the best drug for bipolar depression.

It’s weight-gain is significant, and causes a lot more long-term consequences in terms of other risks.

It helps people sleep, but it’s probably wildly inappropriate in terms of adverse effects to use it for this indication.

I suspect it’s broadly underdosed in clinical practice.

I bet it doesn’t work at doses at which it’s commonly prescribed

There have probably been a lot of lawsuits about it, for illegal marketing.

Let's see how I do over the next series of reviews…starting with an important item: suicidal ideation.

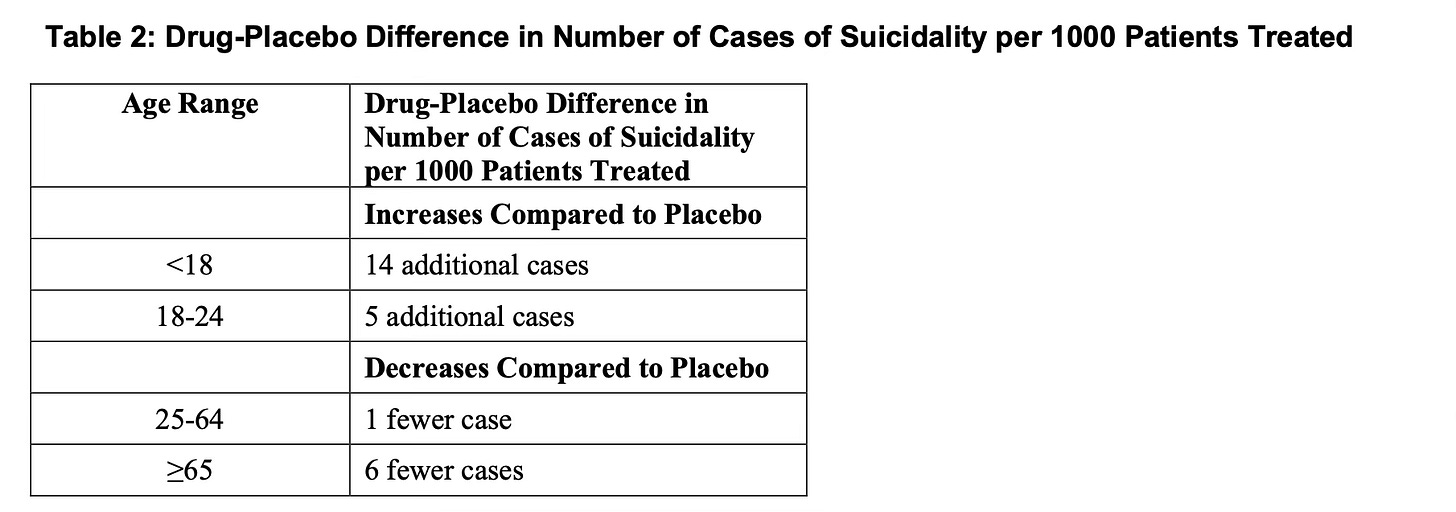

Seroquel makes children more suicidal, and adults less suicidal

The first finding that I did not expect trolling through my new favorite website—accessdata.fda.gov—are the legitimately different rates of suicidal ideation in youth vs adults taking Seroquel.

It’s crucial to note (from the FDA):

No suicides occurred in any of the pediatric trials. There were suicides in the adult trials, but the number was not sufficient to reach any conclusion about the drug's effect on suicide.

We are moving on to schizophrenia, which will be our focus for this first installment. As in many of the columns are right, I'm using this as an excuse to explain the scientific concept. The question at the heart of this article? “How do we deal with missing data.”

Seroquel in Schizophrenia

A meta-analysis authored on the topic of quetiapine monotherapy in schizophrenia1. I'm in an analysis of a meta-analysis author by examines the difference between different methods of handling missing data, and, at least to me, convincingly makes the point that how you slice the cake matters a lot!

Schizophrenia trials have a particular difficulty with dropout. As I previously reviewed in the articles about the Katie trial, the rate of discontinuation in oral medications for schizophrenia is on average 74%2. People stop taking them. But once you even enroll someone in a study, you have to decide what to do about people who drop out. We're trying to avoid the phenomenon of bias, in which we only look at the data from individuals who get to the endpoint successfully.

It's a bit like reporting on running: imagine taking 100 people and asking them to run a marathon, and then only reporting on the people who finished. Your sample would be enriched with people who had been preparing for the marathon, and under-represent people like me, who can barely get down the street because of our arthritis and plantar fasciitis. you need to find a way to represent the limpers’ studies about running. Do you report how far they ran? Dear, how out of breath they were at the time at which they stopped running? Do you ask them how good they felt at the point at which they stopped? Or do you wait till they saunter to the finish line and meet up with their friends, and then ask them? All of these strategies would lead to different interpretations of the data.

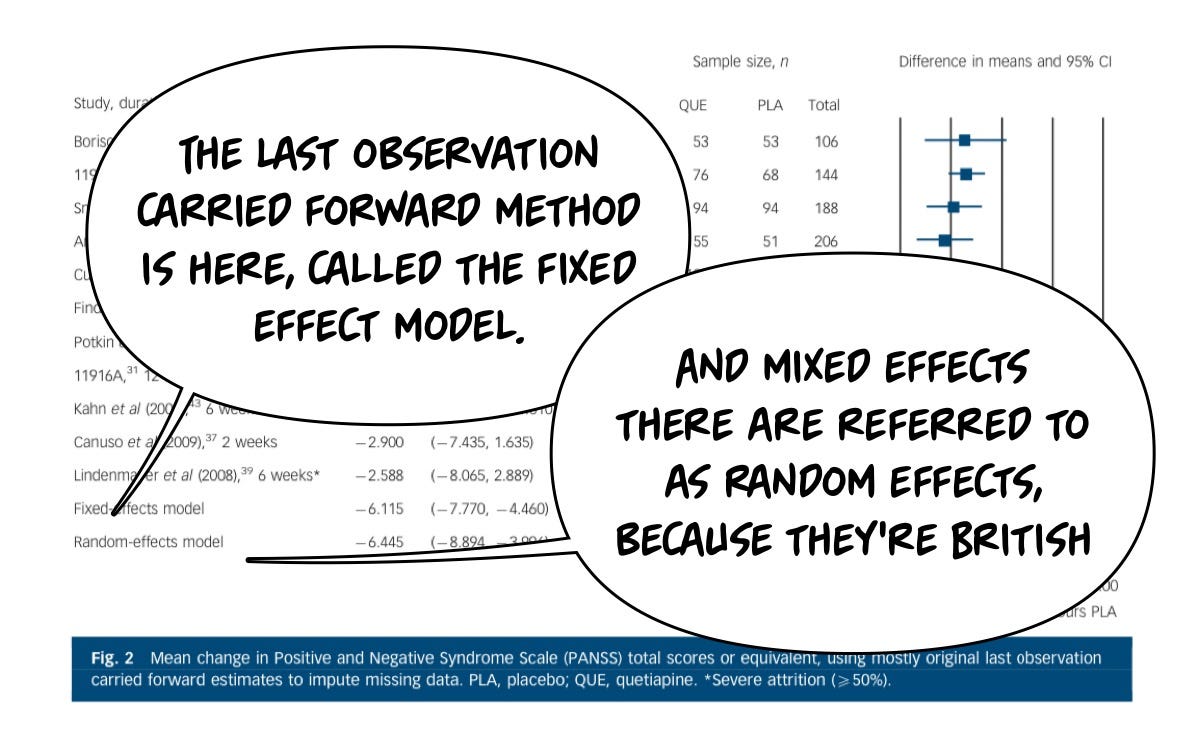

Similarly, decisions need to be made in research trials, and we have two major methodologies with which we can evaluate studies in which individuals drop out. One of those methodologies is called the last observation carried forward method, or (LOCF), and the other is a mixed-effects model (MEM). Both of these approaches, it's worth noting, are better than just ignoring the fact that people dropped out, which is not acceptable scientifically because of the bias introduced.

To briefly compare the two:

Last Observation Carried Forward

What is it?: LOCF fills in these missing data points by carrying forward (to the endpoint) the last available observation for that participant. If you drop out in month 3, the endpoint used in the final math is the endpoint at month 3.

Assumption: The last observed value remains unchanged until the next observation point. This is often an …unrealistic assumption.

Advantages: LOCF is cheap and easy— no fancy stats software, copypasta for the win.

Limitations: What if the reason for data missingness is related to the outcome?!? (e.g., worsening of condition leads to dropout).

Mixed Effects Models (MEMs)

What is it?: MEMs are statistical models that account for both fixed effects (parameters associated with the entire population or specific treatment effects) and random effects (random variations among subjects or time points).

Assumption: MEMs assume that while there may be an overall trend in the population, individual subjects may vary around this trend. It allows for data to be missing at random (MAR).

Advantages: MEMs provide a more flexible and realistic approach to analyzing longitudinal data. They can model the time-dependent nature of data, account for individual variability, and handle missing data more robustly than LOCF.

Limitations: you need to both know something about statistics and buy software that can create these mixed effects models. It's not cheap or free and requires some expertise. That's a real bummer.

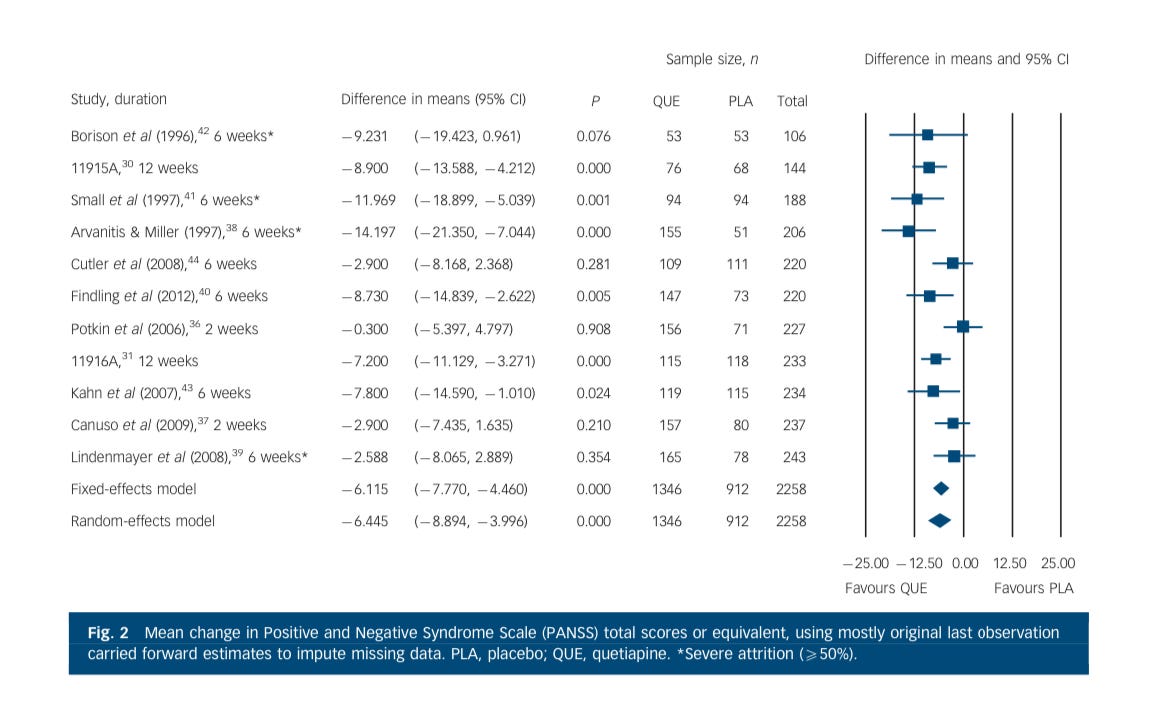

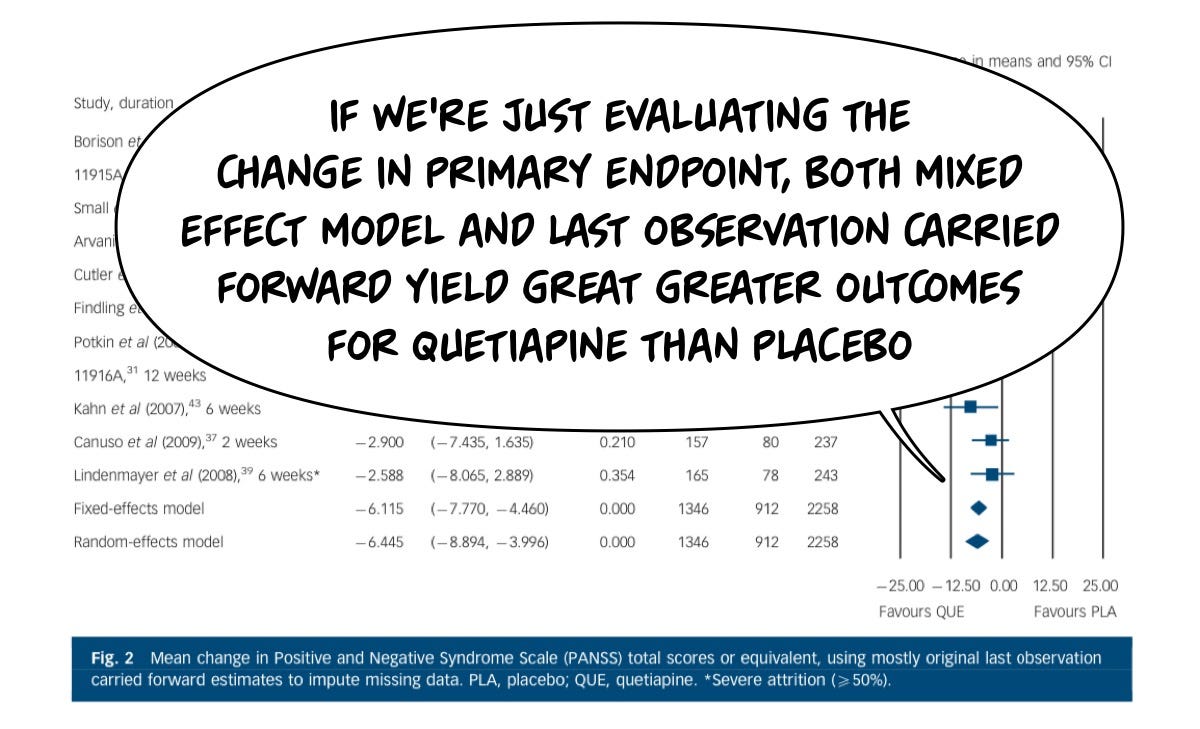

With that relatively dry science explanation out of the way, the data around Quetiapine in schizophrenia. Treatment was modeled in a meta-analysis in which they looked at both what the data looks like with the last observation, carried forward and a mixed-effects model, and they find that it matters how you look at the data!

I previously taught readers how to evaluate a meta-analysis here. You can also brush up on your skills before diving in below with the CATIE trial articles here and here.

Let’s start with the difference between Seroquel and placebo…I’ll just put my comment bubbles in…

Sorry, I put my explanation bubbles in front of this great forest plot. I’m sorry…Let’s they again. This compares a series of studies (left-most) at a duration (next to the study author name) and then in the graph on the right they show each study’s contribution size (square box size). The line through each study…lets know the confidence interval. Here is the figure without my commentary obscuring things:

On the primary endpoint of “average change in psychosis symptoms,” most study subjects did better than placebo with either statistical approach.

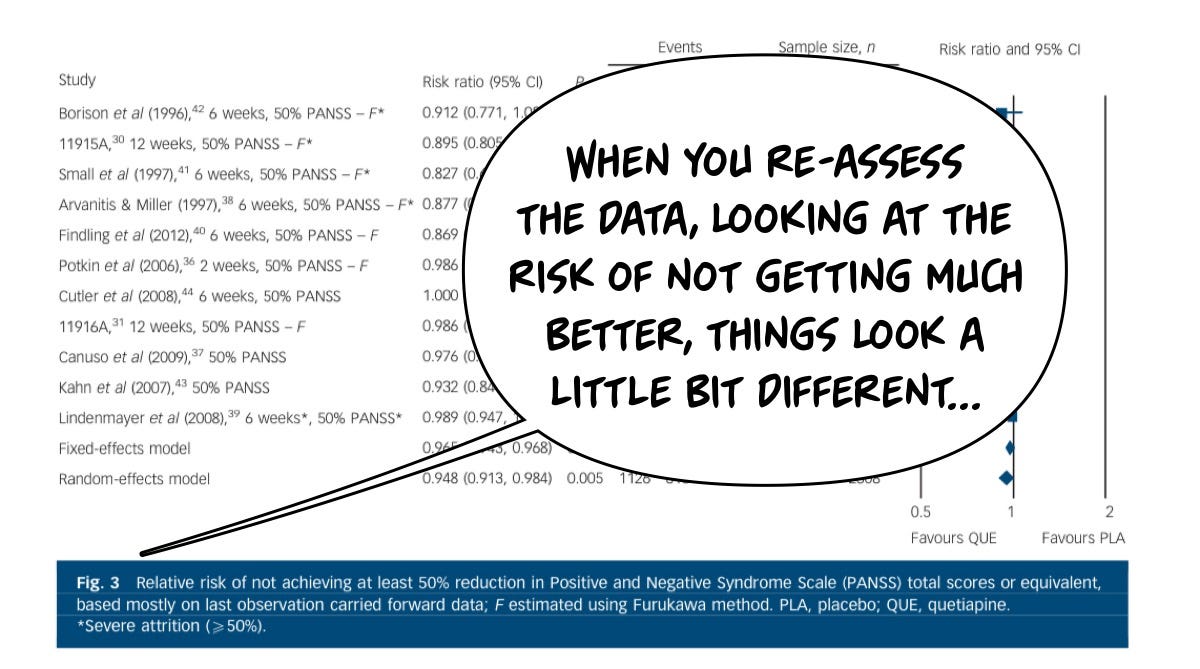

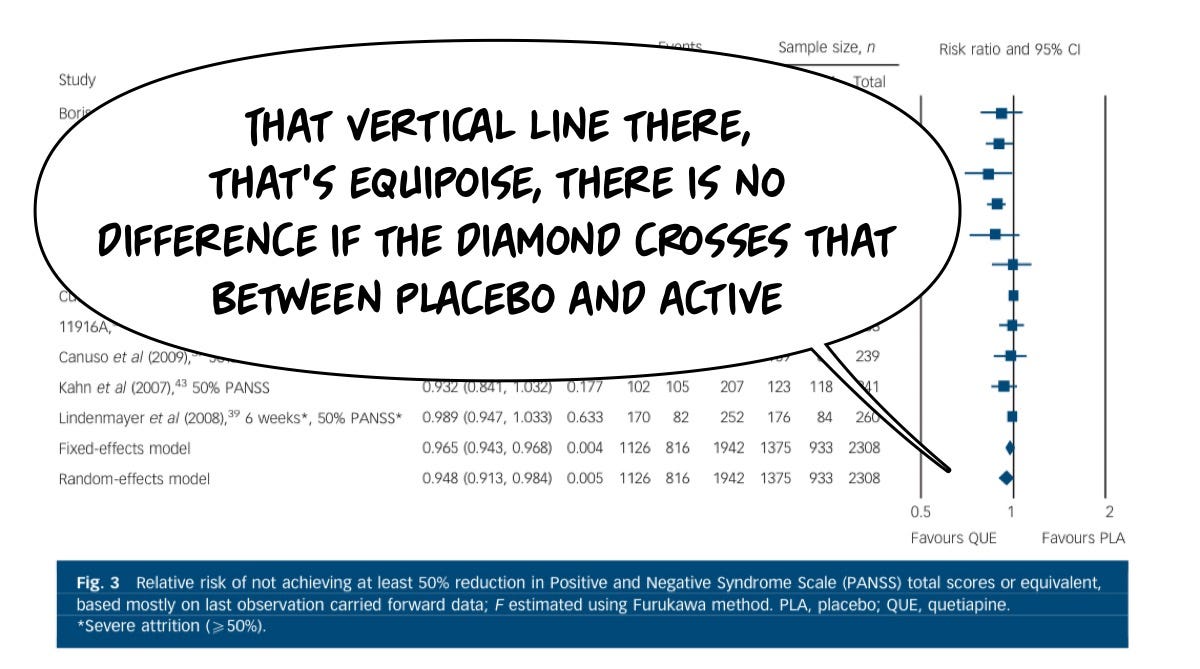

Another way of asking the question of “Did this help” is “What is the risk that it won’t be helpful?”—although the average change across all patients was significant, although the average change across all patients was significant, for many patients, there was not a significant benefit—some people got a lot better, and that pulled the averages into the significant range, but when we look at the relative risk of not getting a big benefit, the numbers look a bit different:

There is a significant cohort for whom Seroquel is not particularly helpful…

And so going back to that same meta-analysis, you can see the diamonds cross that center line, which means they are not different from placebo when it comes to the relative risk of not getting a major benefit (defined as 50% improvement). There are enough super responders that when you slice the data up, the average benefit is good, but the risk that you won't get a great benefit is also high.

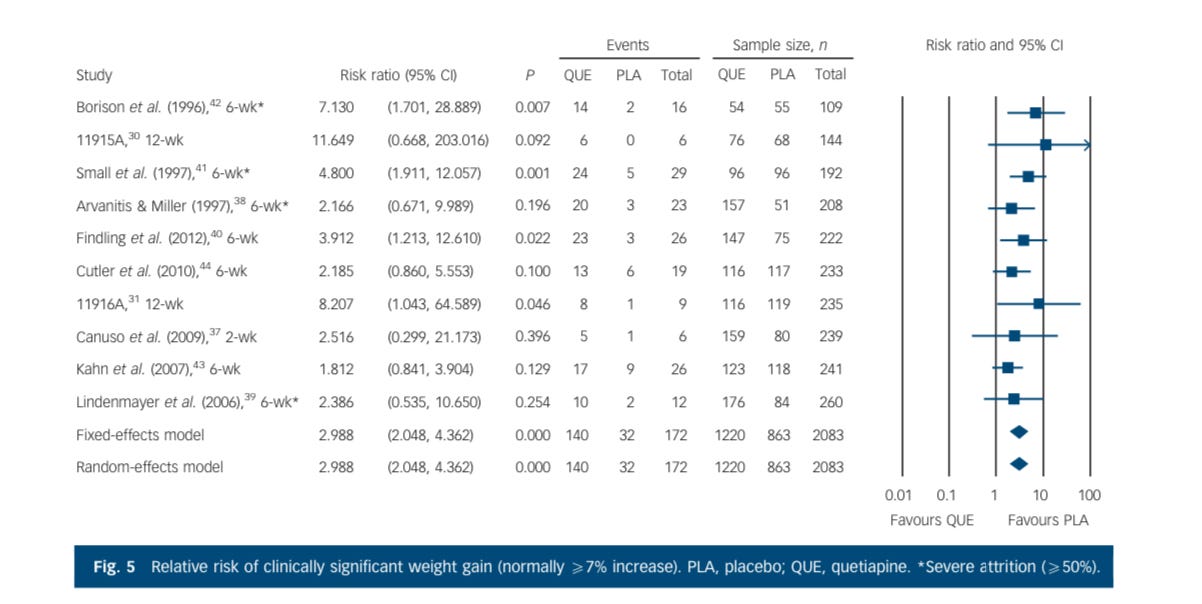

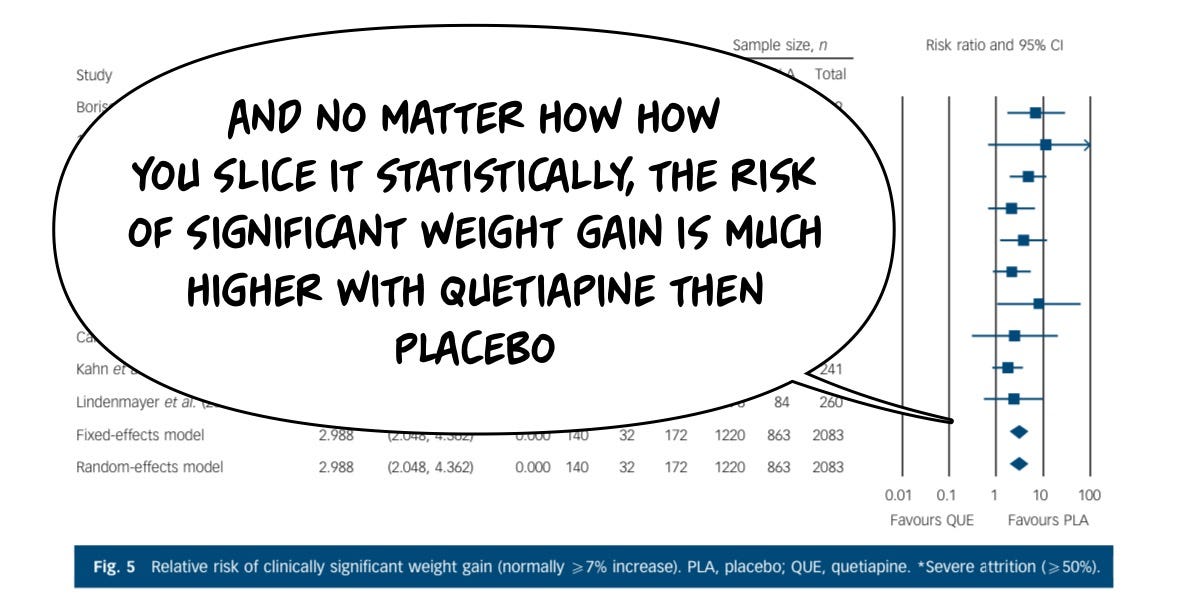

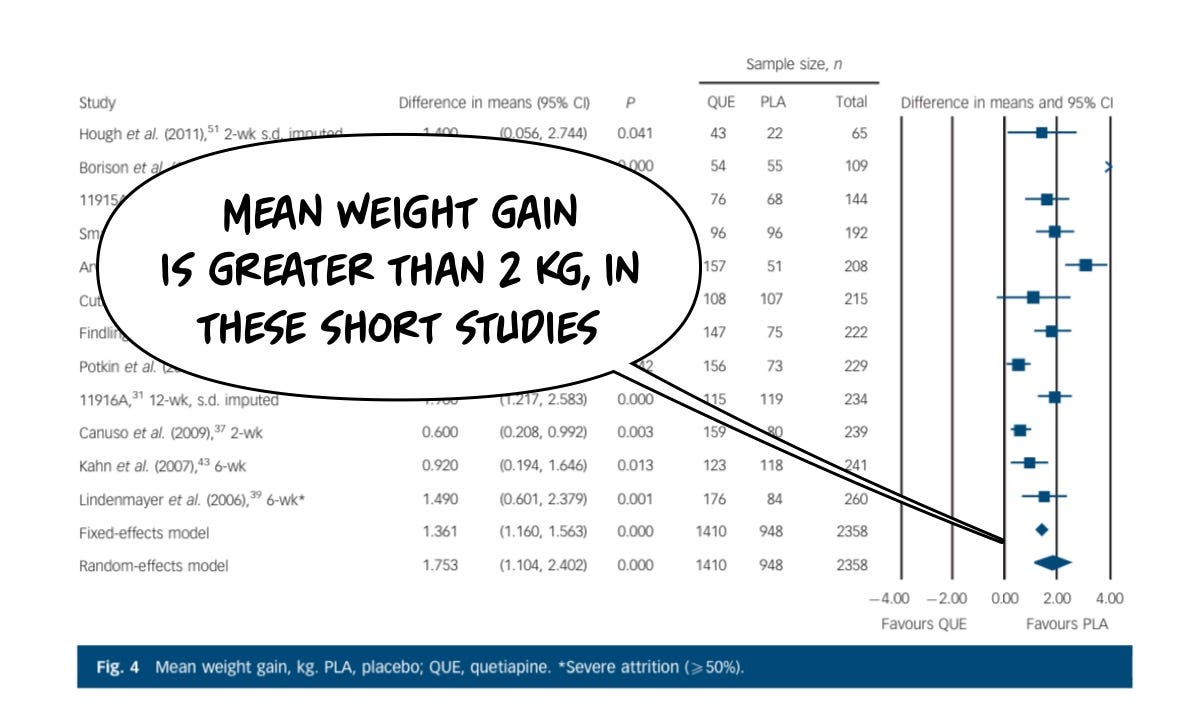

The same cannot be said about the risks of having an adverse effect from the drug, which in this case are headlined by sedation and weight gain. Starting with clinically significant weight gain: placebo is dramatically safer for this risk than the drug, because it causes a lot of weight gain, unambiguously, even in these short trials. You'll notice the longer the study goes on, the more the weight gain.

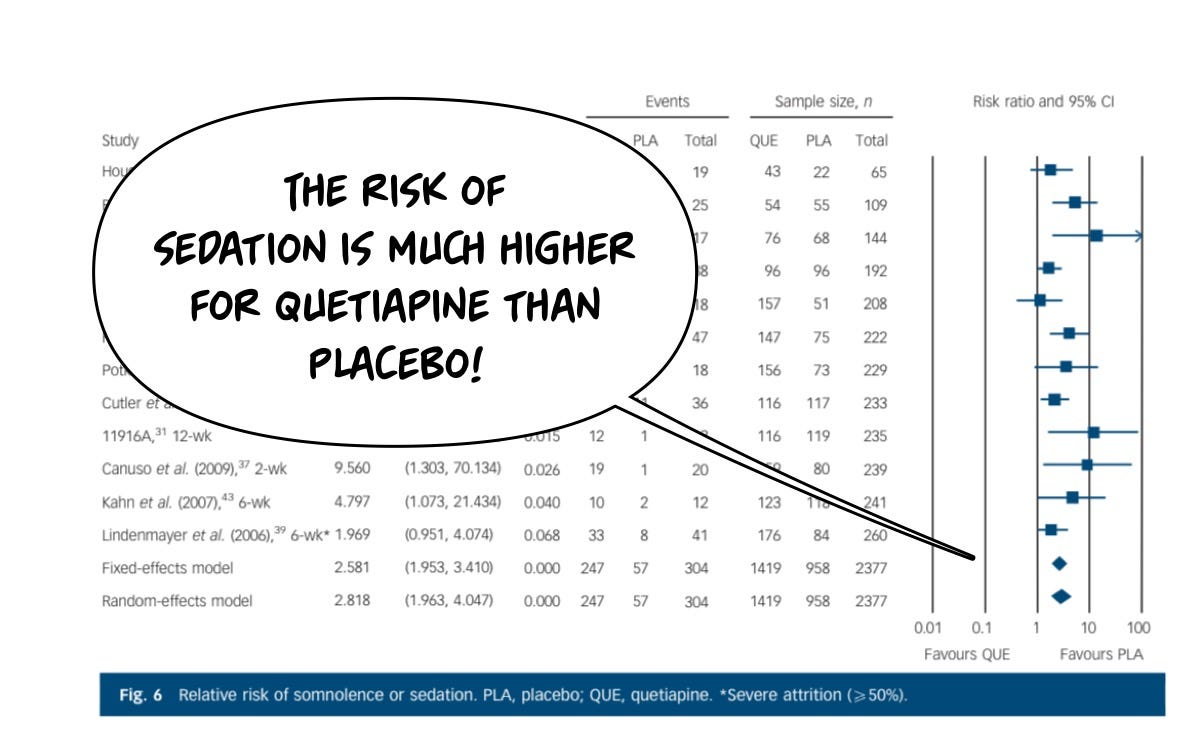

Although sedation is sometimes a beneficial feature of Seroquel, you don't really want to be tired during the day, you just wanna be tired at night, and on the 600 mg doses they use and schizophrenia, more people by a lot are harmed by the sedation of Seroquel then by placebo.

The weight risk is a big deal for everybody:

And the actual amount of weight gained in a relatively short period of time is on the order of 2 kg, this is not trivial, and it doesn't let up meaningfully in longer periods of exposure. Individuals tend to keep gaining weight.

So that's my brief overview of meta-analytic data on schizophrenia treated with Seroquel, and if you want to see how it compares to other drugs, you can look at some of the reviews below. It matters how you look at the data, and it matters how you handle the individuals lost to follow-up. Seroquel is a reliably sedating and obesity-inducing medicine in patients with schizophrenia, but it’s not reliable in terms of being a GREAT medicine for your schizophrenia. On average, it’s better than a placebo. However, that average is skewed—some people get large benefits, but many won’t get a >50% improvement, so many that the chance of being in “the >50% improvement club” is statistically the same as a placebo.

There's more data on this medication and other indications, to stick around for the next episode. If you enjoy these reviews, please feel free to share them, and consider subscribing to the newsletter!

Effexor, Buspar, Risperdal, Zyprexa, Neurontin, Xanax, Klonopin, Paxil, Prozac, Clozaril, Lamictal, Lithium, Latuda, Ambien, and generally Benzos, specifically maybe Benzos leading to death by suicide, Geodon, Zoloft, Auvelity, and over 500 articles total in this newsletter thus far. You should subscribe!

Hutton, P., Taylor, P. J., Mulligan, L., Tully, S., & Moncrieff, J. (2015). Quetiapine immediate release v. placebo for schizophrenia: systematic review, meta-analysis, and reappraisal. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 206(5), 360-370.

Manschreck, T. C., & Boshes, R. A. (2007). The CATIE schizophrenia trial: results, impact, controversy. Harvard review of psychiatry, 15(5), 245-258.