Learn to Read Science Part 1: The CATIE Trial

An annotated walk though on how to read a science paper.

I write about science regularly here in The Frontier Psychiatrists newsletter. I specifically write about research on interventions. You might not believe me. And you should not have to! Today, for subscribers, I will walk you through a classic paper in the world of “effectiveness” research— the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness, as I understand it. This was large-scale NIH-funded research, and I am not an insider. I want my readers to know how to read this kind of paper and feel more confident “doing their research” when it comes to research. This article has a paywall, and I would love to remind you that you can share the newsletter with others to obtain free access to helpful “learn how” articles like this one. I will also be thrilled if you choose to support the work financially, of course.

Let’s start with the very top of the article! That word—Effectiveness!

This paper is not about whether a drug works “in a clinical trial.” It is research about how drugs (plural) work in the real world. It’s published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM)— that matters. This is one of the most critical journals in medicine. Based on the journal, my suspicion that this will be important is increasing. It’s a big deal journal. All journals have a “big deal” score called an impact factor so they can compete. As of this writing, the impact factor of NEJM is 176.079.

It’s the most high-impact medical journal. Other big leagues are… (with impact factor) …

New England Journal of Medicine. (176.079)

The Lancet (British edition) (168.9)

JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association (120.7)

BMJ. British Medical Journal (International ed.) (107.7)

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (12.08)

Annals of Internal Medicine. (39.2)

BMJ Open. (2.9)

MEDICINE. (1.552)

American Journal of Psychiatry (17.7)

The score, for reference, is calculated as follows: dividing the number of times articles were cited by the number of articles that are citable.

There is tremendous pressure to keep that number up. One of the ways of doing this for journal editors is to publish studies with large sample sizes. In this regard, effectiveness research is a good strategy because, almost by definition, we are talking about large sample size research.

Let us take a look at the abstract:

BACKGROUND

The relative effectiveness of second-generation (atypical) antipsychotic drugs as compared with that of older agents has been incompletely addressed, though newer agents are currently used far more commonly. We compared a first-generation antipsychotic, perphenazine, with several newer drugs in a double-blind study.

Ok, we are going to compare new medicines with older medicines. There is no placebo group. This is just comparing things that work, and it will be randomized and double-blind and randomized.

METHODS

A total of 1493 patients with schizophrenia were recruited at 57 U.S. sites and randomly assigned to receive olanzapine (7.5 to 30 mg per day), perphenazine (8 to 32 mg per day), quetiapine (200 to 800 mg per day), or risperidone (1.5 to 6.0 mg per day) for up to 18 months. Ziprasidone (40 to 160 mg per day) was included after its approval by the Food and Drug Administration. The primary aim was to delineate differences in the overall effectiveness of these five treatments.

The methods section is crucial, and they tell us—it’s a lot of people! Almost 15001! We know the patients have schizophrenia; it’s from 57 different sites (which is a lot of sites, and we have data that effect size decreased with more sites in a trial2), and they tell us the drugs compared and the dose ranges. We know a lot already. We will spend more time on methods, don’t worry. I’m already thinking…

“I wonder what inclusion and exclusion criteria were? Who were these 1493 subjects? What kept someone in or out of the trial? Who on earth would agree to 18 months of random medicine?!?

And, of course, the real cliffhanger: HOW WILL THE AUTHORS DECIDE HOW TO MEASURE OVERALL EFFECTIVNESS? That is a lofty goal! Keeping with the abstract, the results section…

RESULTS

Overall, 74 percent of patients discontinued the study medication before 18 months (1061 of the 1432 patients who received at least one dose): 64 percent of those assigned to olanzapine, 75 percent of those assigned to perphenazine, 82 percent of those assigned to quetiapine, 74 percent of those assigned to risperidone, and 79 percent of those assigned to ziprasidone. The time to the discontinuation of treatment for any cause was significantly longer in the olanzapine group than in the quetiapine (P<0.001) or risperidone (P=0.002) group, but not in the perphenazine (P=0.021) or ziprasidone (P=0.028) group. The times to discontinuation because of intolerable side effects were similar among the groups, but the rates differed (P=0.04); olanzapine was associated with more discontinuation for weight gain or metabolic effects, and perphenazine was associated with more discontinuation for extrapyramidal effects.

Wait, 74% of patients discontinued their medicine? Yes. That is how they decided to measure if the medicines studied were “overall effective”—not if the subjects got better, just if the medicine was worth taking for 18 months.

Which, overwhelmingly, they were not.

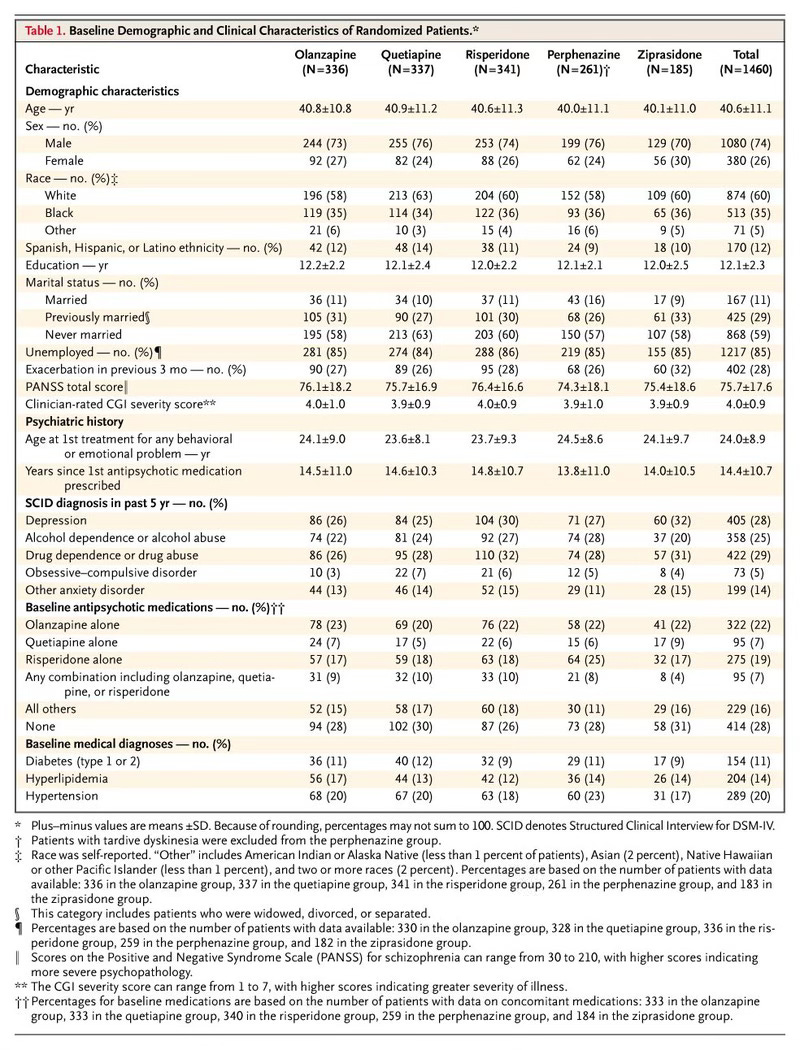

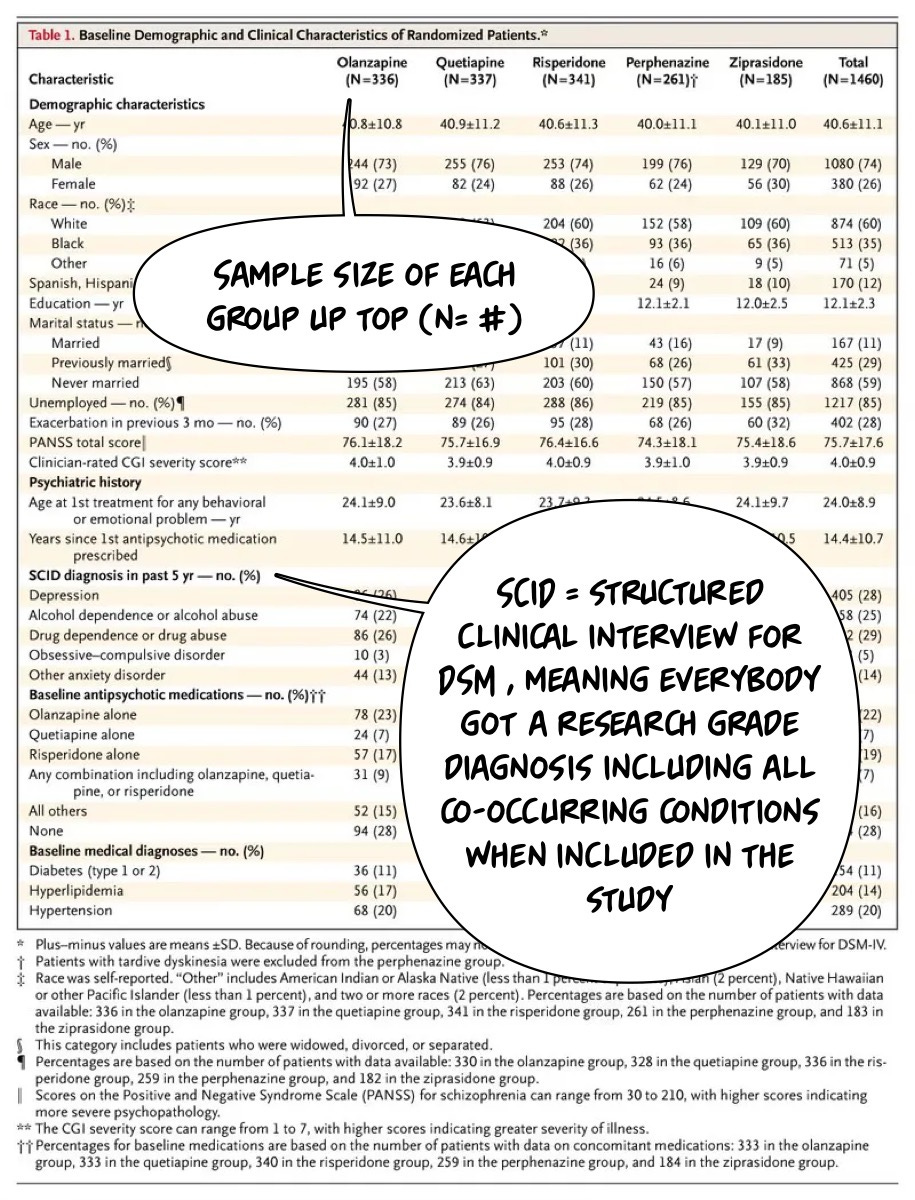

Let’s dig into Table 1, which tells us who is in the trial…the issue is that this is a very imposing table for most of us. I think it scares people off from thinking that you can dig in and understand this stuff if you're part of the general public. The opposite, I would argue, is accurate, and I will try to prove it to you. Here it is…

I have written about Table 1 before, and I would suggest readers review that article and this one, too. I will use the helpful text bubbles to walk us through this table! I will start by making a few observations:

They told us the sample size and the diagnosis! And the authors tell us how they got the diagnosis. The SCID (newest version linked there)! What about the age of the participants in the study?