“I Did Not Want to Be Angry All the Time”: Mental Health Clinicians’ Attitudes About Insurance

Original research.

Today, a recap of a Frontier Psychiatrists classic. Remember when taking the insurance was viewed as virtuous by mental health professional professionals? When companies like Talkiatry decided to build the entire businesses where the whole pitch is it's psychiatry that takes insurance? Well it turns out, when you ask clinicians what they think about taking insurance, the attitudes are not always positive. Recent media coverage has pointed out that the experience can be just as shredding as the connections in this original research pointed out. Feel free to review any of the coverage ClearHealthCosts or ProPublica have done. Is a grim business. It still needs to exist, but it does need to get a lot better when it comes to parity. This article presents original research we did on the topic of the attitudes health professionals have towards insurance, and I leave it to my readers to make their own decisions about the data.

What do mental health professionals think and feel about taking insurance? It turns out there is research in the academic literature that answers this question, but just qualitative explorations.1 Many mental health clinicians don’t take insurance.2 It’s a problem.3 People were, and are, starting companies left and right based around the hypothesis that making the process of taking insurance easier is going to lead to a great company, but no data exists to support the fundamental hypothesis that mental health professionals want to take insurance in one particular way or another. So we did the research.

So I’m doing a thing that people don’t do. Or at least that I don’t do. I’m taking a paper that was written, initially, to be a scientific research paper. And I’m not publishing it in a journal. Neither is Carlene.4 I am going to give credit to my co-authors!5 I’m not publishing it in a journal for a couple of reasons: The first, and most personally important, is that editing papers for journals is really freaking boring. Like, so freaking boring that my ADHD demanded I give up.

This research has been years in the making, and the ability to dictate it into an iPhone with Siri means—at long last—you will get to read it. It does not mean that it will be submitted in some unbelievably stale format to JAMA Psychiatry, or any of the other journals that would give it prestige…

Instead, it’s going to be here, on The Frontier Psychiatrists!

This is original research that was IRB-approved (in an indie rock move, we used an independent IRB, Sterling, instead of spending our time waiting for six months for an academic institution to further delay this publication).

The thing that was really making me dread getting this done and submitting it to a proper academic journal, beyond just the “avoidance of tasks that require sustained mental effort” (yes, this is a criterion symptom of inattentive type ADHD), is that it had to be written in a way that was really boring. We also had to get the word count down and have different citation formats for different journals. And frankly, I’m really busy, and pretty tired, and I just couldn’t. Writing for academic journals requires a complete lack of humor, which is not my “academic orientation”.

This is more than an academic question however—the hypothesis that we need more in-network options is popular among investors and startups:

I needed to finish this insurance attitudes paper. Academic journals were unappealing for another reason: it’s not a particularly engaging format. You’re kept, intentionally, away from rhetorical flourish and entertaining word play. Writers are supposed to act like they are unopinionated to make it feel more sciencey.

Science, in my world, has a particular meaning: what it means is taking a hypothesis, and subjecting it to the horrific possibility that the massive amount of work you’re doing is going to be sufficient to prove your hypothesis wrong. Science is all about falsifiability. It’s the academy’s version of Asphyxiaphilia—exciting edge play, but with the possibility of annihilating the rest of your (academic) life.

Sciencey writing on the other hand, is to give the impression that what you were reading is scientific. And for some reason we’ve decided that boring and scientific are the same thing. As if detachment should be cultivated above and beyond all other virtues.

I’ve got news for you: scientists, or at least this scientist, and others I know, give an empirically high number of 🚽s about what they do. They tend to care a lot that their research has positive findings, because that is rewarded. They care a lot that the research gets published in high impact journals, because that’s prestigious and validates their existence.

Writing with a sense of unbelievably—and I mean I literally don’t believe it— bland detachment somehow provides a force field against accusations that you’re not a scientist.

If your writing is sciencey enough, no one could possibly suspect you cared about the result. Or that you had an agenda. However, both of those contentions are almost axiomatically true. Thus, the blandness is, one must assume, intentionally misleading. This is about as disingenuous as this passive aggressive note, left on the refrigerator in a workplace:

In order to make a point, and make it possible for me to finish this goddamn thing, I am going to write in the mild to moderately entertaining voice that I generally do. At the same time, I’m going to present objective evidence gathered in the service of a hypothesis. I’m not gonna pretend I don’t care what the outcome is. But I am going to present the data in a way that allows you to make your own decisions. Plenty of bias was involved—I have a similar relationship to big healthcare payers that Spartans had to long winded diatribes.

By the way, a pro-tip for people reading journal articles in scientific journals: you can skip most of the writing. I think introductions are important to frame the ethical argument for why you’re doing the work you’re doing in the first place, but if you’re a serious scientist, introductions are basically fluff. Human subjects research matters.6

Similarly, the discussion section of research articles is entirely spin. It’s dry and sciencey spin.7

If you want to consume a hell of a lot more research than you currently do, and you’re in the kind of business where that’s a thing that you need to do on the regular, save yourself a metric F ton of time—learn how to read methods, and learn how to read results. And leave it at that. If you know what the researchers did and what they found, you’re basically done. Everything else is a waste of your time, on average. I hope that’s helpful. Charles A. Sorenson, Ph.D., my advisor in college, taught me this lesson late in my Amherst College career, where and when I was already an opinionated member of the technorati, and it has saved me an endless amount of time ever since.

With that series of sassy disclosures concluded, we’re now going to get into the meat of this particular piece of original academic research. I’m going to include an abstract, and all the regular science stuff, but I’m not gonna write entirely in the same dreadfully detached tone that makes one certain I have an ulterior motive. My glaring conflicts, emotional and financial, will be made very clear, like I usually do. I hope the experience will be one that is refreshing for my readers, and helps us reconsider how we think about science writing.

My stylistic move, by the way, is to take the asides, and put them in the

blue line at the side, as if it’s a quote format, like this

to distinguish them from the science writing that is a bit more dry. And now, drumroll please:

“I Did Not Want to Be Angry All the Time”: Mental Health Clinicians’ Attitudes Towards Taking Insurance

Abstract:

Sciencey Objective: To ascertain mental health clinician attitudes towards and experiences with health insurance companies.

Actually axe we intended to grind: At the time this research was done, the lead author Carlene MacMillan, M.D. and myself, as well as our co-authors, worked in a private outpatient practice where we took insurance. We strongly suspected that our colleagues hated working with insurance as much as we did. So we decided to ask them. We were not disappointed.

Design: This was an observational, cross-sectional study.

Rationale for design: it was easy. We just sent out a bunch of questionnaires after we got an IRB approval for the questionnaire. To do more for a first paper on the topic when we frankly didn’t know what people would actually say seemed like more work than it was worth.

Methods: A web-based questionnaire was sent via social media and professional distribution lists.

Bias built into that approach: By utilizing the methodology of accessing clinicians who are active participants in listservs and social media groups, we heard from people who are on average more engaged than people who don’t do that. So, these are clinicians who think about stuff and care enough to talk to each other about it. They’re not clocking in and clocking out. They are not necessarily representative of all mental health clinicians.

Participants: Three hundred mental health clinicians participated in the survey.

This was, of note, pre-pandemic lockdown. The survey was sent around in February and March, 2020. If only we knew! This was coincidentally 300 in number, but I’m going to freely reference King Leonides of Sparta and his fight at Thermopylae anyway…

Results: Sixty-six percent of mental health clinicians surveyed accepted insurance. Twenty-seven percent of the sample had previously accepted insurance, and then resigned from insurance panels. Ninety-eight percent reported experiencing stress when dealing with insurance companies.

The following conclusion, I have to say, is the kind of thing you have to include in a sciencey research write up, but it’s basically a recapitulation of what you’ve already seen in an abstract. And the words waste your time. That’s me including them just to hammer home that point:

Conclusions: In this observational, cross-sectional study, mental health clinicians identified stress and poor reimbursement as major reasons for not taking insurance.

It needs a title…

But something with a bit of sizzle would probably get more readers, like:

We asked 300 clinicians what they thought about taking insurance, and had to take a shower subsequently because we felt so unclean just thinking about what they told us.

Sciencey Introduction:

Nearly one in five adults in the United States is living with a mental illness.8 However, the current mental health care system is failing to provide effective and accessible treatment.9

62% of adults with mental illness do not receive treatment and 21% perceive their treatment needs are unmet. Forty-two percent of the population state that the top barriers to mental health care are high cost and poor insurance coverage.10 Limited access to mental health resources, along with cost, stigma11 and disparities12 prevent many from accessing the care and support they need.

This creates an endless litany of things for me to complain about in this newsletter, but probably demands some more exploration of what the actual causes are!

But yeah, a disproportionate number of mental health clinicians don’t accept insurance compared with other medical specialities.13 A 2013 study determined only 55% of psychiatrists accept insurance compared with 89% for all health care professionals14. According to a survey by the American Psychological Association, 38% of psychologist respondents did not accept any insurance.15 Financial reasons and the additional working hours required to accept insurance are often cited in the popular press, which I assume now includes this substack.16

There has been little research into the attitudes of clinicians towards working with insurance.17 To our knowledge, and this is true, nobody has ever asked mental health professionals why they don’t take insurance as part of a study. Not systematically. This is the first time. For real. Nobody asked why. (Which, in all fairness, might be the unofficial slogan of healthcare in 🇺🇸 ).

Methods:

Using an observational, cross-sectional study design, our survey included questions to assess both qualitative and quantitative data regarding the attitudes of mental health professionals towards working with insurance as a way to accept payment for care they provide. The study received a certificate of exemption status from the Sterling Institutional Review Board. Data was collected from February to March 2020. This time frame alone kinda explains why it took so long to publish this.

Participants:

Inclusion criteria required the participant to be a licensed mental health clinician. Sorry, life coaches! A 20-part questionnaire was created using surveymonkey and distributed to mental health clinicians. Subjects were recruited from various online mental health clinician groups. The survey was posted on line through LinkedIn, Facebook clinician-only groups, The American Psychology Law Society listserv, and psychology research forums. Three hundred participants completed the questionnaire. Responses remained anonymous and all surveys were completed online.

The Questionnaire:

Questions focused on clinician experience working with insurance payment models, their role as a clinician and experience in the field. The first portion of the questionnaire asked participants to rate their feelings towards insurance on a 5-point Likert scale. The survey then evaluated the clinician’s level of satisfaction toward working with insurance. There was one qualitative question asking for personal experiences with insurance. The survey can be reviewed in Appendix A.

Analysis:

Quantitative analyses included summaries of the Likert scales and multiple choice questions. Qualitative coding was used to assess the open text and “other, please specify” responses. Both quantitative and qualitative results were incorporated to provide a more comprehensive view of clinician attitudes toward the questions.

Results:

Profession, Training, and Work Setting:

Mental Health Clinicians in this survey included:

Psychiatrist MD/DO,

Nurse Practitioner,

Psychologist,

Mental Health Counselor,

Social Worker,

Other Masters Level Therapist,

and other/specify.

The breakdown of the 300 respondents was as follows: :

Social Worker (26%),

Psychologist (25%),

Mental Health Counselor (21%),

and Psychiatrists MD/DO (18%).

Other professions (10%) specified:

Substance Abuse Counselor,

Clinical Hypnotherapist,

Program Director,

Executive Assistant,

Licensed Psychological Associate,

Licensed Professional Councilor,

Mental Health Practice Owner,

Marriage and Family Therapist

Psychotherapist.

The average number of years since completion of professional training was 3.82 years. 25% of the respondents were between 1 and 5 years post graduate years, and 30% were at least 16 years after graduating from their training program.

The work settings in the survey were characterized as:

Private Practice (Self-Employed)

Private Practice (Other)

Hospital Setting

State or Locally Funded Setting

Group Practice

Other

This sample skews heavily towards outpatient private practice. Of 300 respondents, 61% worked in self-employed private practice and only 5% worked in hospital settings.

Among the specified other areas, an academic setting was mentioned most frequently, followed by non-profit agencies, nursing homes, and outpatient clinics. Additionally, correctional facilities, mental health agencies, federally qualified health centers and integrated primary care were included.

Radical Insurance Acceptance

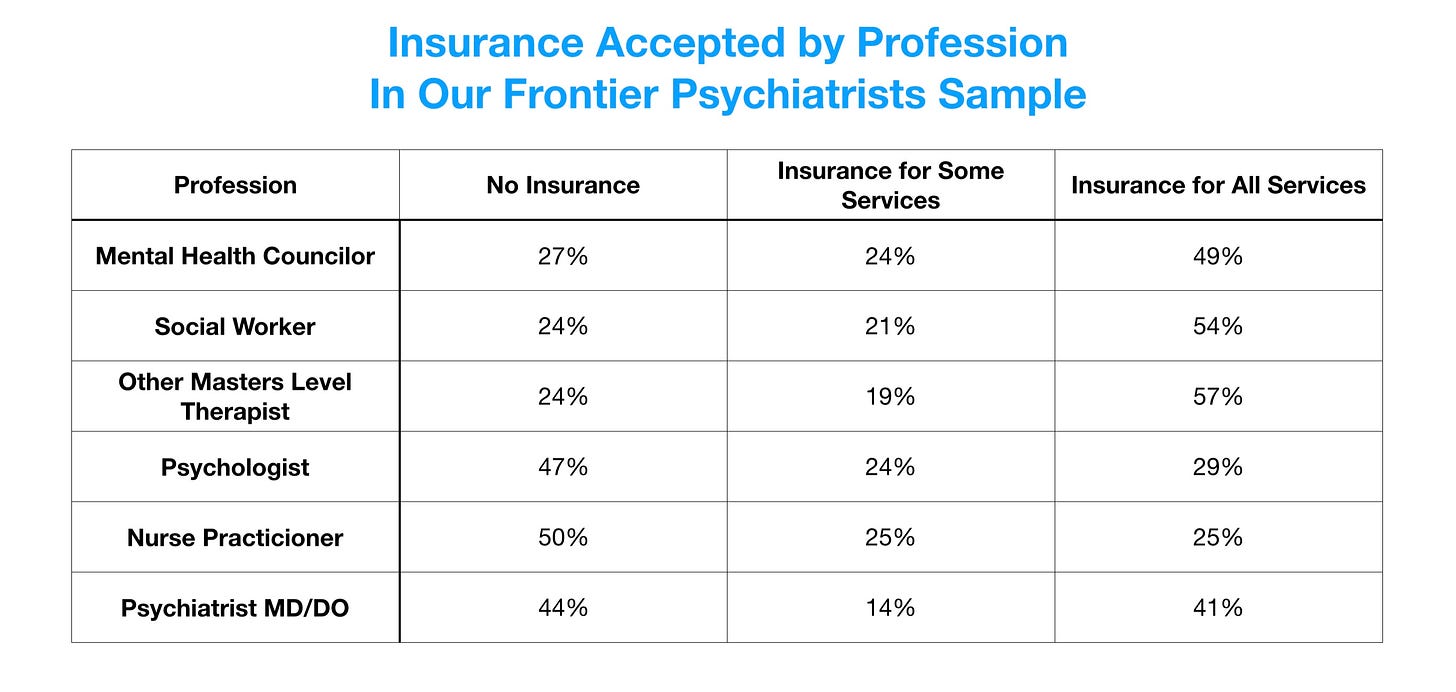

Two thirds of the represented practices (66%) accepted a level of insurance (45% for all services, 14% for most services and 7% for a few select services). However, 34% of practices took no insurance whatsoever. For Psychiatrists (18% of all respondents), approximately 55% accept some level of insurance (41% for all services, 7% for most services and 7% for a few services), and 44% did not accept insurance at all (Table 1).

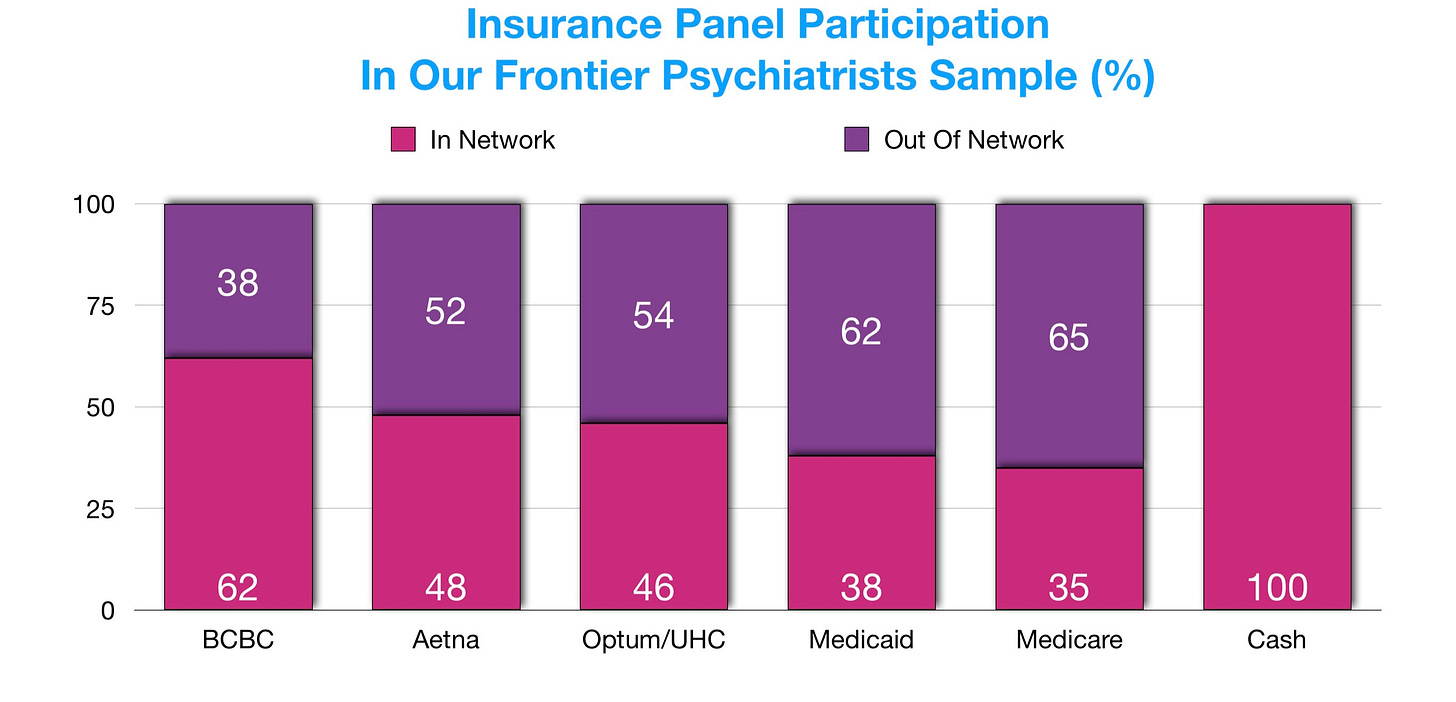

We collected data on the types of insurance accepted by mental health clinicians:

Approximately 27 percent of the insurance plans were mentioned less than 5 times.

For the respondents who did not accept insurance for all services, we requested reason(s) “why not”:

Of the 166/300 respondents who didn’t take insurance at all, 23% selected that insurance does not reimburse enough for the services provided in the respondent’s workplace, 18% felt it took too much time to deal with insurance companies, 15% selected that is was too stressful to deal directly with insurance companies, and 14% felt accepting insurance involves too much paperwork.

Tell Me Why: Reasons for Not Accepting Insurance

I will remind the audience that our sample was identical in sample size to the Spartans at Thermopylae! 300 responded to the survey. Standing shield to shield, virtually, they resolutely held back the hordes of third-party payers with the following internal rationale:

The “other” section was free text and thematically coded. Findings indicated 4 major themes:

Limited by resentment of payer control over clinical care.

Limited by type of work.18

Limited by coverage of services provided by clinician.

Limited by low payment.

Having the work that you do controlled by insurance companies was not popular:

“I do not want a corporation directing what kind of therapy I provide to my clients, or the timeline. I also do not like the idea of breaking clients' confidentiality to corporations.”

Keeping off the radar was popular:

“I fundamentally object to how insurance companies do business. I also like allowing my patients the option of having their treatment totally off-record.”

Limitations in pay were tragic-comically underscored:

“6 years with no raise.”

And, in a more quotidian voice:

“Some people have a really high deductible through their insurance so they would rather do our self-pay rate because it is more affordable in the short term.”

One respondent recounted their experience with insurance companies below:

“Was initially credentialed with all the big insurance companies, which was helpful for patient access in my rural and very underserved community. But after a couple of years of trying to make it work, I had to leave insurance panels. I did not want to be angry all the time. All the bureaucratic hoops that they continually created. Denials, prior authorizations, errors in mailing addresses that took months to fix despite hours on the phone with multiple people, complicated phone trees that make it challenging to speak to an actual person, and their collective invalidating and disrespectful attitude towards physicians. It was too much.”

27% of respondents were on an insurance panel and resigned. Low reimbursement rates, distrust, non-payment even when prior authorization was received and the complexities of dealing with insurance companies were reccurring themes among resigners:

“Could no longer deal with the time, energy and anger generated by the insurance company's continuous refusals or failure to pay, and in particular not being able to speak to a live person to rectify the situations that came up regularly.”

Experience With Insurance: Imagine Sisyphus Writing a Review on Glassdoor

A brief note: Not every respondent answered every question, which depended on their answers to prior questions. That’s the reason for different sample sizes in the following section:

Out of 121 responses:

45% deal with insurance personally.

31% have someone in the practice who deals with insurance.

24% have an external billing department that deals with insurance companies.

In perhaps the least shocking finding of this entire study, of 121 respondents, asked about the helpfulness of insurance companies:

58% said “very or somewhat unhelpful.”

23% felt “neither helpful or unhelpful.”

15% indicated “very or somewhat helpful.”

The time spent waiting on the phone really stood out for 113 respondents:

Nearly 50% of respondents typically waited over 15 minutes to speak with a representative of an insurance company, with 3% waiting over an hour.

“We Got This”

As a moment of bias-in-sample-awareness, I will underscore that the people giving the answers you’re reading are those who overwhelmingly (just under 2/3rds) feel very or somewhat capable of dealing with insurance! This is not a cohort overpopulated with people who feel like they don’t know what they’re doing. These numbers are as bad as they are among people who understand themselves to be good at the task!19

Nothing’s Certain but Death and Taxes… and Time Wasted Waiting for a Representative

Our respondents spent a lot of time dealing with insurance companies. Of the 114 responses:

22%: more than 10 hours per week.

20%: 1-2 hours per week.

18%: 30 minutes to 1 hour per week.

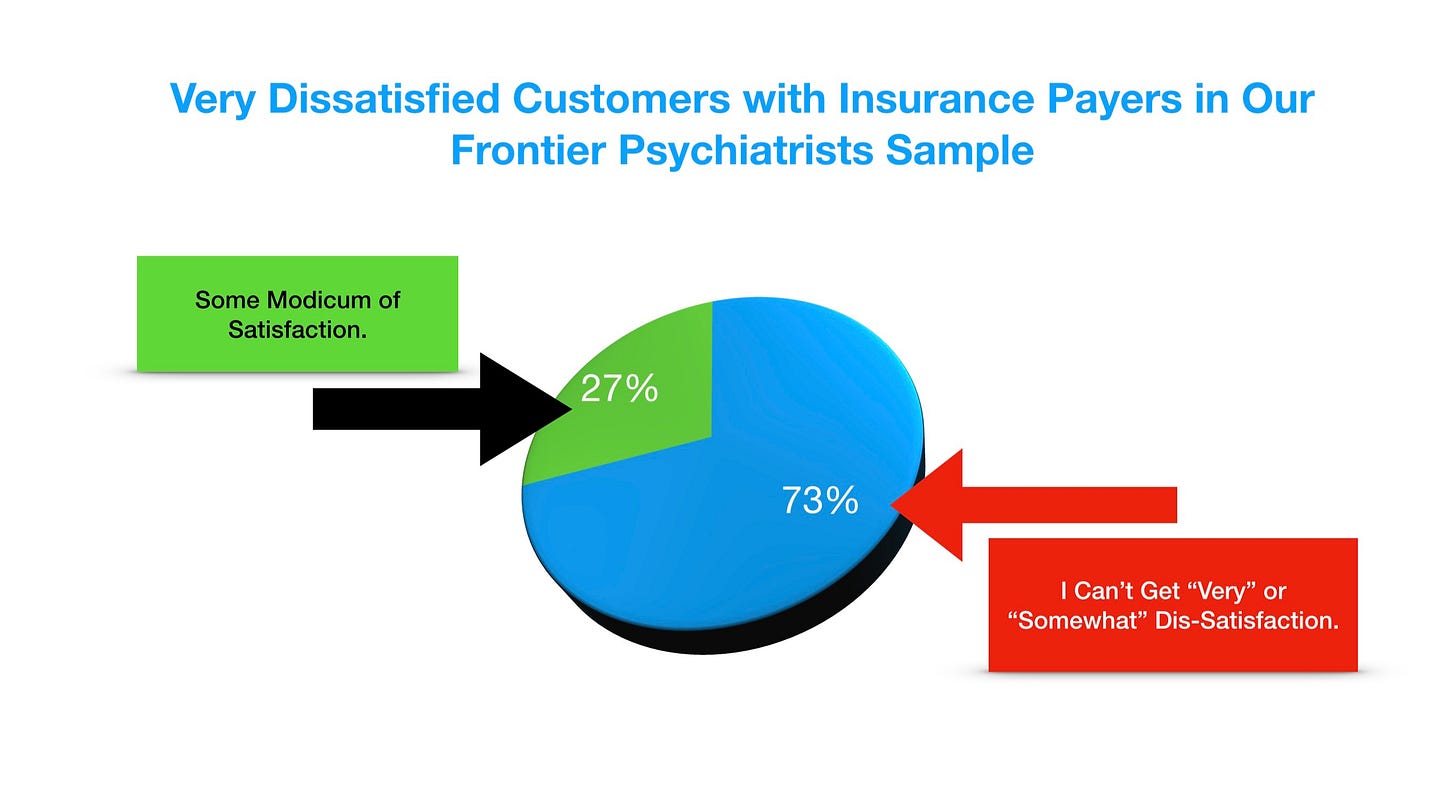

I Can’t Get No Satisfaction… With Mental Health Care Coverage

Seventy-three percent of the 122 respondents were very or somewhat unsatisfied with mental health insurance coverage. This deserves a graphic:

Thirty-three percent indicated the experience was very stressful. 70% of the respondents who felt very incapable also felt it was very stressful dealing with insurance companies.

Policies and Authorizations

Eighty-five percent of respondents indicated that insurance policies had a negative impact on patient care. Only 4% felt a positive impact, and 10% had no opinion. Practices that never requested prior authorizations from insurance companies for care represented 35% of the responses. Twelve percent submitted more than 10 per week. Nearly half of the 111 responses indicated never having prior authorization rejections. However, 36% have them 1/3 of the time and 15% less than half the time.

Reflections From Respondents

Participants were asked to share any highlights or low points in working with insurance companies:

Highlights were all related to the feel good nature of access for patients:

It can feel good to provide services to people who could not otherwise afford it (which at this point is a minority of my insurance clients).

Practice growth is a sentiment that built several startups since this study:

Makes therapy more accessible to people, helped me get my practice off the ground quickly.

Alma’s 130M Series D Investors agree…

Low, Low, Low, Low, Low Lights

Feelings of “not being valued” by insurance companies was a major theme in the low point responses.

To wit:

“Feeling my work is not valued by these companies”

“I only take plans known to be friendly to psychiatry”

“I refuse to involve myself with a company that treats people (providers and patients) this way.”

It’s insulting:

“The amount most insurance companies reimburse is less than 50% of what I would take for clients who pay cash. No one takes mental health care seriously and it is insulting and frustrating”.

It’s impossible:

“Claims are not always handled appropriately—I am told the Member ID is wrong when it is the number on the patient's card and on the insurance company's website. Customer service is not trained to handle problems and does not seem to have correct information uniformly. It is impossible to get a supervisor or other knowledgeable person on the phone to resolve anything.”

Providers feel they take the blame for problems:

“Lack of patient education about insurance, so patients generally blame the provider rather than the insurance company when there is an error.”

Intimidation was a factor:

“Having insurance companies clawback and deny claims for valid services and seeing my peers in other states get audited seemingly for intimidation purposes.”

Discussion

Some people hate working with insurance. That’s the long and short of it. Insurance is stressful to deal with. And it doesn’t pay enough. We can get paid more otherwise. And so, and unsurprisingly, we don’t accept it. Or we do, because it seems like the right thing to do for society, but then we learn the apparent errors of our masochistic ways and resign from the panels.

Our data suggests that the problem with taking insurance is not that it’s complicated and the workflow needs to be disrupted, per se. That is true. But it’s not the most important truth. The most important truth is that, for mental health conditions, a system that is stressful, feels controlling, and underpays you by a factor of many multiples of what you could be making otherwise is not a sustainable business model for clinicians. Thus, the endless platform solutions that are doing clinicians a service by making it easier to take insurance are in for, possibly, a really harsh awakening unless they can change the way payers value the mental health clinicians in their network. Paying a few dollars more per claim is not going to cut it.

This is a serious problem for the business models of all clinicians who take insurance and all mental health platforms. I’m looking at you Alma. I’m looking at you, Grow Therapy. This extends, of course, to Talk Space, Better Help, etc. Because at the end of the day, all they’re doing is creating value off of the work of licensed therapists.

Their path to scale is by working with insurance. And the path to success for therapists and psychiatrists, is, as we can see from the above data, to resign from insurance panels or never take them in the first place.

These force clinicians to take insurance as service platforms haven’t been around long enough to have their panels of therapists all quit. But essentially, there’s a bait and switch going on, because even if someone’s making it easier to take insurance, which is clearly reducing the stress of the process, it doesn’t solve the problem of being paid multiples less than you’re worth.

In NYC, there are people who are willing to pay me $1,000 an hour in private practice. I know psychologists who also make that kind of money. I know social workers who make $300 a session. I know psychologists who make $500 a session. On the other hand, I know therapists who are paid $30 a session, working with multiple platforms and on insurance panels. Practically, if you’re working with a platform solution like Alma, they’re raising hundreds of millions of dollars on the premise that they can get you to work for less. Our data says, even before that was a thing, people didn’t want that. Clinicians have already rejected the basic premise that these platform solutions are building upon.

The insurance rates paid to therapists are absurd. Maybe these platform solutions will do a better job of negotiating those contracts, but it’s not that much better. I’ve seen a seven dollar reimbursement rate offered for group therapy. On a good day, a masters level therapist is getting under $100 for a therapy session from insurance. On a great day, they’re getting $200. But they’re not getting $1,000. They’re not getting $500. They’re not getting $300.

If your business pitch is trying to get therapists to sign up for a platform so they can make less money, well then you gotta hope that’s a compelling pitch. And our data suggest that it’s not. The issue is that therapists are not in the business of scalability. Not yet anyway. And platforms that aren’t making therapist’s skill sets meaningfully more scalable are dealing with a scarce and limited resource. The time of therapists is at non-scalable 45-minute or 60-minute blocks, x number of times per week. This has a limit. A bunch of different companies scrambling to get pieces of that limited pie is going to make for a couple of exits, but it’s not gonna change healthcare. And therapists are going to quit. And then they’re going to go back to doing less scalable work, and everyone’s gonna be worse off.

Therapists are kind. They have sliding scales. They like to reduce their fee to help people. That’s really nice. But nice doesn’t scale a business. And arbitrage on the difference between what we therapists think is nice and what people are actually worth is a fine strategy for a company until it’s not.

Through our cross-sectional study, we obtained a representative sample of mental health clinicians across disciplines to assess their attitudes and experiences with insurance. A striking 98% of respondents who have worked with insurance companies reported some level of stress in dealing with them. Insurance should ideally bridge the gap between the patient’s need for treatment and their financial resources. However, the current fee-for-service model incentivizes the rejection of valid claims, increases demands for prior authorizations and increases administrative burden—all sources of stress for many mental health clinicians.

Work Setting, Professions, Training

A majority of the respondents in this study described their practice setting as “self-employed and other private practices.” As essential workers in these practices, time for dealing with insurance companies is often limited. In fact, 70% of respondents felt incapable of dealing with insurance. Training in fundamentals of payment systems could help clinicians navigate the insurance system. Still, this would not address frustrations related to bureaucratic friction and low reimbursement.

Twenty-seven percent of mental health clinicians in our sample resigned from insurance panels. This is similar to data from Bishop and colleagues’ article, which found a shift away from third party payers. Although many mental health clinicians have sought to take insurance in their practices, satisfaction with insurance payers was low. Given the occupational stress of mental health care, the added stress of dealing with insurance and the inability of patients to obtain needed coverage can contribute to moral injury in clinicians.

Solutions for Mental Health Clinicians

Our survey results identify multiple pain points experienced by clinicians working within the current health insurance model in mental health. These flaws highlight the fundamental misalignment of payment, quality, and quantity of care. Right now much of mental health spending goes towards covering inpatient hospitalizations, PHPs, and IOPS, leaving little left over for the outpatient clinicians who represent the majority of our study population. The rates paid by third-party payers are often lower than prevailing private pay rates, and this makes it difficult to justify working in a more frustrating system that pays less than market rates.

The current demand for mental health care is high enough to support a large private pay market. However, most patients, particularly those with serious mental illness, lack the financial resources to access this market. Moreover, in order to win back mental health clinicians, insurance providers must offer solutions to address the poor reimbursement and administrative burden that drives clinicians into the private pay market. Systemic solutions for addressing the pay gap and bureaucratic pushback would include enforcement of existing laws that regulate mental health parity and prompt payment. Additionally, enforcement of existing laws that regulate mental health parity, prompt payment, and other statutes would make the adversarial attitude sometimes encountered by clinicians less “hazard free” for payers.

Myriad regulatory issues keep the status quo more-or-less frozen in place. Currently, more fee-for-service policies are prevalent in mental health care, though interest in value-based care has been increasing. Value-based care is a compensation model designed to reimburse the clinician based on patient outcomes rather than dictating specific treatments. It includes measures to document and assess processes and outcomes, as well as generate cost savings. In a value-based model, outpatient clinicians would be rewarded for keeping their patients out of the hospital, thus directly linking clinician financial incentives with improved patient outcomes. In this shared risk model, clinician and payer goals would be more closely aligned and there would be less incentive for payers to block payments for needed care.

Other novel opportunities exist in areas of the mental health care landscape where there are more degrees of freedom, including self-funded employers. These organizations are “on the hook“ for the performance of their plans, and it is the argument of the authors of this document that performance- or value-based reimbursement much more closely resonates in the world in which these costs can be contained.

Based on a study in Washington state, value-based payment improved fidelity to collaborative care models and improved patient depression outcomes. At this time, however, only small pilot programs exist in outpatient mental health. As more such programs are implemented, it would be important to evaluate clinician attitudes and satisfaction compared to the more traditional fee-for-service model.

In primary care, the imposition of intensive outpatient programs and partial hospitalization programs prevent innovation in higher but not the highest acuity cases. (This sentence needs clarification.) Furthermore, unlike psychiatric care, medical hospitalization does often offer options that are not available in outpatient care. The opportunity for behavioral health providers who are willing to go “at risk“ and work in teams that approximate the acuity managed by IOP/PHP/some inpatient providers is coming. Our providers need to be ready to embrace this opportunity in which getting the right answer for your patients and failing to do so share the same incentive structure.

Correcting the misalignment of financial incentives in the traditional insurance model is essential for expanding the pool of clinicians willing to accept insurance and providing greater access to mental health care for our sickest patients. We see a shift towards shared-risk, value-based care as a way to reduce the stress clinicians experience interacting with insurance providers. With better incentives for participating in these programs, clinicians need to be ready to embrace the opportunity to be rewarded for finding the right treatments for their patients.

Study Strengths and Limitations

This study has a representation of mental health clinicians at various levels in diverse work settings. Surveys in mental health have typically had low response rates and this is one of the first to surveys of mental health clinicians with a decent sample size. The study is limited by the omission of a non-mental-health-clinician perspective, which is needed to compare experiences.

Future Research

Expanding research to compare insurance experiences with non-mental health clinicians would assist in strengthening the experiences of mental health clinicians. Additionally, gaining the perspective of insurance companies about working with mental health care would be helpful. Future work should also include repeating the study after value-based care has been actively used by mental health clinicians. Continuing to study the experiences of mental health clinicians will further highlight these issues and lead to improvement in mental health care.

Conclusions

Value-based care would assist in reducing the contentious relations between mental health providers and insurance companies. Additionally, increasing education in insurance company selection and use in mental health professional programs and continued education trainings for professionals already working in the field would be helpful. Insurance is beneficial to mental health care, but increasing reimbursement rates, reducing fees, and providing better assistance are essential in order to continue to increase access to mental health care.

References

Smith T, Myers R, Sederer L, Berezin J. How value-based payment arrangements should measure behavioral health. Health Aff Blog. 2016 Nov. Retrieved from https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20161129.057660/full/

Carlo AD, Benson NM, Chu F, Busch AB. Association of Alternative Payment and Delivery Models with Outcomes for Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Jul 1;3(7):e207401. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.7401. PMID: 32701157; PMCID: PMC7378751.

Bao Y, McGuire TG, Chan YF, Eggman AA, Ryan AM, Bruce ML, Pincus HA, Hafer E, Unützer J. Value-based payment in implementing evidence-based care: the Mental Health Integration Program in Washington state. Am J Manag Care. 2017 Jan;23(1):48-53. PMID: 28141930; PMCID: PMC5559616.

Lien YY, Lin HS, Tsai CH, Lien YJ, Wu TT. Changes in attitudes toward mental illness in healthcare professionals and students. In J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Dec; 16(23): 4655. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6926665/

Walker ER, Cummings JR, Hockenberry JM, Druss BG. Insurance status, use of mental health services, and unmet need for mental health care in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(6):578-584. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201400248

Wood P, Burwell J, Rawlett K. New Study Reveals Lack of Access as Root Cause for Mental Health Crisis in America. National Council for Behavioral Health. 2018, October 10. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/press-releases/new-study-reveals-lack-of-access-as-root-cause-for-mental-health-crisis-in-america/. Accessed October 11, 2020.

Reasons identified by author Carlene Macmillan MD include: “I’m way too unmotivated to submit this to a journal— The UI/UX experience of journal submission is far below the standards I’ve come to expect”

Carlene McMillan, M.D., Danny Ruiz, MHC. Valerie Merced, MHC-LP, Rebecca Sinclair, Ph.D. Owen Muir, M.D.

The ethics around human subjects research matters. Tremendously. Humans should not be subjected to research to answer trivial questions. And unfortunately, this happens all the time. Introductions are to make an ethical argument. This matters, it’s not trivial. But other than that, there’s no real contact there. If you’re trying to learn something new, don’t bother with that.

But spin nonetheless. It’s the Fox News chat show of academic research articles.

National Institute of Mental Health. Mental Illness. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.shtml. Published 2020. Accessed October 11, 2020.

… and …

Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):168-176. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2174588/

Rowan K, McAlpine D, Blewett L. Access and cost barriers to mental health care by insurance status, 1999 to 2010. Health Aff (Millwood). Health Aff (Millwood). 2013 Oct; 32(10): 1723–1730. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4236908/

… and …

Frank RG, Goldman HH, Hogan M. Medicaid and Mental Health: Be careful what you ask for. Health Affairs. 2003 Jan/Feb; 22(1). Retrieved from https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.22.1.101

Knaak S, Mantler E, Szeto A. Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare: Barriers to access and care and evidence-based solutions. Healthc Manage Forum. 2017 Mar; 30(2): 111-116. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5347358/

Evans TS, Berkman N, Brown C, Gaynes B, Weber RP. Disparities Within Serious Mental Illness [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016 May. Report No.: 16-EHC027-EF. PMID: 27336120.

… and …

Cook BL, Trinh NH, Li Z, Hou SS, Progovac AM. Trends in Racial-Ethnic Disparities in Access to Mental Health Care, 2004-2012. Psychiatr Serv. 2017 Jan 1;68(1):9-16. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500453. Epub 2016 Aug 1. PMID: 27476805; PMCID: PMC5895177.

Lake J, Turner MS. Urgent Need for Improved Mental Health Care and a More Collaborative Model of Care. Perm J. 2017;21:17-024. doi:10.7812/TPP/17-024

… and …

National Alliance on Mental Illness. The Doctor is Out: Continuing Disparities in Access to Mental and Physical Health Care. Arlington: National Alliance on Mental Illness; 2017. Retrieved from https://www.nami.org/Support-Education/Publications-Reports/Public-Policy-Reports/The-Doctor-is-Out/DoctorIsOut

… and …

Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):176-181. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862

Hamp A, Stamm K, Lin L, Christidis, P. 2015 APA Survey of Psychology Health Service Providers. American Psychology Association; 2016. https://www.apa.org/workforce/publications/15-health-service-providers/report.pdf

Benjenk I, Chen J. Trends in Self-Payment for Outpatient Psychiatrist Visits. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online July 15, 2020. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2072 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/article-abstract/2768024

See 10, above.

Dembosky A. Frustrated You Can’t Find a Therapist? They’re Frustrated, Too. NPR; 2016, July 14. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/07/14/481762357/frustrated-you-can-t-find-a-therapist-they-re-frustrated-too. Accessed on October 11, 2020.

… and ….

Pear R. Fewer psychiatrists seen taking health insurance. The New York Times; 2013, December 11. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/12/us/politics/psychiatrists-less-likely-to-accept-insurance-study-finds.html Accessed on October 11, 2020.

… and …

LoCicero A. Can’t Find a Psychologist Who Accepts Insurance? Here’s Why. Psychology Today; 2019, May 2. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/paradigm-shift/201905/cant-find-psychologist-who-accepts-insurance-heres-why Accessed on October 11, 2020.

Rowan K, Shippee ND. Experiences with Insurance Plans and Providers Among Persons With Mental Illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2016 Mar;67(3):282-8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400514. Epub 2015 Nov 16. PMID: 26567930.

Seven responses indicated a limitation by type of work, such as working with or within the criminal justice system, in low resources areas, no costs for services provided, and funding by a grant. Six respondents feel limited by coverage, such as not being available to cover all services provided or even in areas in which they provide the services.

Twenty-two percent of the 122 respondents indicated “very or somewhat incapable” of dealing with insurance companies. However, 65% felt very or somewhat capable.

Brought me back to a patient who for 10 days had been without her script for abilify which she had used for years very stably to treat bipolar disorder. She had changed jobs and therefore insurance companies, and the "fill my script"/ "cover my meds" (or whatever the hell that money making interface between the provider and insurance company is called) people did not register it. Patient did not know she could pay out of pocket. I had been dutifully filling out the fill my meds/script whatever over and over. But: wrong form!! And no one knew that!! Now-patient huddled in the corner of my office, suicidal, off the meds, fired from her job. I am on the phone nicely taking down Bartleby the Scrivener's name on the other end and then telling Bartleby that if this patient kills herself I will be contacting the Boston Globe and naming their company. Remember: we are being recorded for quality assurance purposes-use it to your advantage!! 10 minutes later the approval form was faxed to me. Next step is unionizing like the MGB PCP's are doing. Great article.

You. are. a. BRILLIANT. writer!