Xanax

Because the opiate crisis isn't bad enough

The Frontier Psychiatrists is a newsletter by noted medical content creator1 Owen Scott Muir, M.D.

This series is on individual medicines. Data is presented and referenced, but it's a farewell to prescribing. I learned psychopharmacology, but it's not the focus of my career anymore. Other installments in this series include Klonopin, Lurasidone, Olanzapine, Zulranolone, Benzos, Caffeine, Semeglutide, Lamotrigine, Cocaine, Xylazine, Lithium, dextromethorphan/bupropion and Adderall, etc.

I also take requests from subscribers—this whole series is by request from the inimitable Kari Groff. Thanks for reading, and please— support the work!

By the 1960s, treatment had been medicalized. The first psychotropic drugs were discovered by serendipity and introduced into psychiatry. The symptom relief they brought was so startling and persuasive that there was a major shift from psychologic to pharmacological treatment.

—Leon Eisenberg, M.D., the Stepfather of Laurence B. Guttmacher, M.D.

Alprazolam is a benzodiazepine medication that has the brand name Xanax. It has an FDA label for “Panic Disorder, with or without agoraphobia.”

In my Klonopin piece, and my prior general benzo review before that, I talked about lipophilicity—how fast a drug can get into the brain, based on how soluble it is in fat. A lipid bilayer protects our brain from drugs inviting themselves in, Willy Nilly.

It gets into the brain fast. It has a short half-life—the liver breaks it down rapidly. Xanax is fast in and fast out. Was the drug concocted to be abused? With Xanax, You won't even remember you asked2.

The world would be better if nobody ever knew it existed. Those doctors who promoted it lied to themselves. One of the Xanax evangelicals told me so himself.

Laurence Guttmacher, M.D., is his name. He was an older man when we met. He is very tall. My mother immediately remembered meeting him over a decade ago when I read this article to her on a first pass:

“He thanked me for allowing us to train Owen as a psychiatrist,” she noted.

He is an advisory dean at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry. In the first week of medical school, the first lecture he gave me was about not allowing drug reps into the hospital.

Only 15 years later, writing this, do I apprehend how haunted he was by the pharmacology he mid-wifed. He has written a medication guide and an older historical ECT manual, too. He spends time teaching now.

Dr. Guttmacher is in the family business. He is a third-generation psychiatrist. His grandfather was the president of the American Eugenics Society—he took over from Margaret Sanger, the champion of the birth control pill. It kept undesirable people from having more children. Laurence Guttmacher is an American Jew. Eugenics was re-purposed from utopian, enlightened, Jewish, and intellectual ideals by Nazis. It was promptly used against the same Jews and other “feebleminded undesirables.” The subsequent rejection of medicalization of psychiatric distress is understandable, among largely Jewish analysts, given Nazis (again, from Drs. Guttmacher and Eisenberg):

Psychoanalysis helped psychiatry preserve an abiding interest in the individuality of patients while other medical specialists were losing sight of the patient in their preoccupation with the biology of the disease. It connected the symptoms of mental illness to the psychopathology of everyday life. Psychiatrists learned to help patients by paying attention to their mental symptoms in an era when psychiatry had no procedures. …When [psychoanalysis] was banned from the Congress of Psychology at Munich as ‘a Jewish science’ in October 1933, psychoanalysts in Berlin and Vienna began to migrate to the UK and the US. …some 100–200 European analysts and some 30–50 analytically orientated psychologists emigrated to America in the 1930s… the membership of the American Psychoanalytic Association was only 135 in 1936 and almost doubled to 249 by 1944 …[This] influx was as significant intellectually as it was numerically; many refugees … became leaders in the movement.

This was Laurence Guttmacher’s inheritance—idealism about mind or brain—gone, catastrophically, south. His father and mother were quixotic psychiatrists as well.3

Psychoanalysis was potent because it explains something. People love explanations— but don't often demand that they be correct. Before the age of oral medicines, psychoanalysis offered these:

No other psychologic theory provided what was purported to be so comprehensive an account of the origins of psychopathology. The brain sciences were largely irrelevant to clinical practice. In the mid-century, descriptive psychiatrists were held in little esteem because the diagnosis was unreliable and made little difference in treatment. The psychiatric pharmacopeia was limited to hypnotics and sedatives.

This changed with Thorazine. The push towards “biological” explanations continued with the advertising efforts of fellow psychiatrist Dr. Arthur Sackler. His advertising firms, which he purchased and disguised his control of, were behind campaigns for drugs like Valium, Thorazine, Serax, Miltown, and the rest. This was well before his feckless son, Dr. Richard Sackler, took his portion of a family business and murdered undesirables with Oxycodone.

Physicians love to be scientific-ish. We love the sense of science. We love an explanation. Laurence Guttmacher loved explanations. Xanax worked—plus, safer than Miltown. As he would later write, doing some heavy editing for his late stepfather:

The influence of the authority of one’s teachers, the experience of seeing patients improve during psychotherapy (most non-psychotic patients did), the logic and malleability of psychodynamic explanations, and the readiness with which patients desperate for a way out of their dilemmas accepted those explanations combined to make believers of all but the most skeptical of trainees. Those who were non-believers were easily dismissed with ad hominem attacks on their unanalyzed resistance.

In that week one lecture in medical school, Dr. Guttmacher was my authoritative teacher. The lesson? Be accountable, even for violations of good sense one has yet to commit.

That class featured slides on the percentage of doctors who felt drug representatives had influenced them— according to themselves. A scant one percent admitted to any possibility of influence by industry. The same physicians’ opinions about colleagues—99% of them above any influence, remember— were presented on the next slide.

In my first week of medical school, Laurence Guttmacher highlighted our credulousness, 40% of the same physicians understood their colleagues would fall under the thrall of attractive drug reps. Physicians were justly suspicious of Pharma’s influence on everyone—except ourselves. This, of course, was exactly the pitch Arthur Sackler was making—as far as I can tell, he was an astute psychiatrist.

Physicians love to be helpful. What is the most addictive substance for physicians? Samples!4 We can give them to our patients. We loved it when our office staff were gifted treats. We are “jonesing” to be gracious. We get hooked when people listen to us!

Industry paid for all this. Arthur Sackler’s disciples were not high on their own supply, unlike individual physicians—intoxicated by how beyond reproach they were.

They paid for us to talk to each other, and they paid more if the person being listened to said the right things about Xanax. Administrative staff? Lunch. The same devious machinations of Italian grandmothers—Mangia!— were deployed to influence physicians. There were attractive people to listen to us about how much we cared and our desire to be gracious—the Sacklers ensured it. Arthur was a psychiatrist, after all— someone to hear you out feels good.

We had so much to teach. Dr. Laurence Guttmacher researched panic disorder at the National Institute of Mental Health earlier in his career. He was a compelling speaker for Xanax, given his panic disorder pedigree from NIMH.

One morning, he awoke to a horrible realization: Xanax wears off after 3-4 hours. Everyone waking up (after 8 hours of sleep) was in Xanax withdrawal. That feels like a panic attack. The obvious cure, next to the bed, was the first of four Xanax tablets as prescribed and recommended—by Dr. Guttmacher in well-appointed dinners—throughout the day. The next day, this cycle of panic would begin again, but this time, worse. And the next day, a little worse still. This was a cycle of self-reinforcing madness. But it moved product.

In one of the more demonic decisions ever made, Xanax was formed into a convenient “bar” with four subdivisions. This allowed someone to break 2 mg apart and take 0.5 mg four times a day.

No one would ever think to take it all at once. Unless they were anyone, in which case, this is the most immediately obvious strategy.

Xanax is a nightmare. It makes opiate—and other— overdoses endlessly more lethal. It’s illegal in the UK and should be pulled from the market everywhere. This drug of abuse doesn’t need to be an answer to an exam question on medical boards, ever again, unless it is under the “obviously unethical compounds” section.

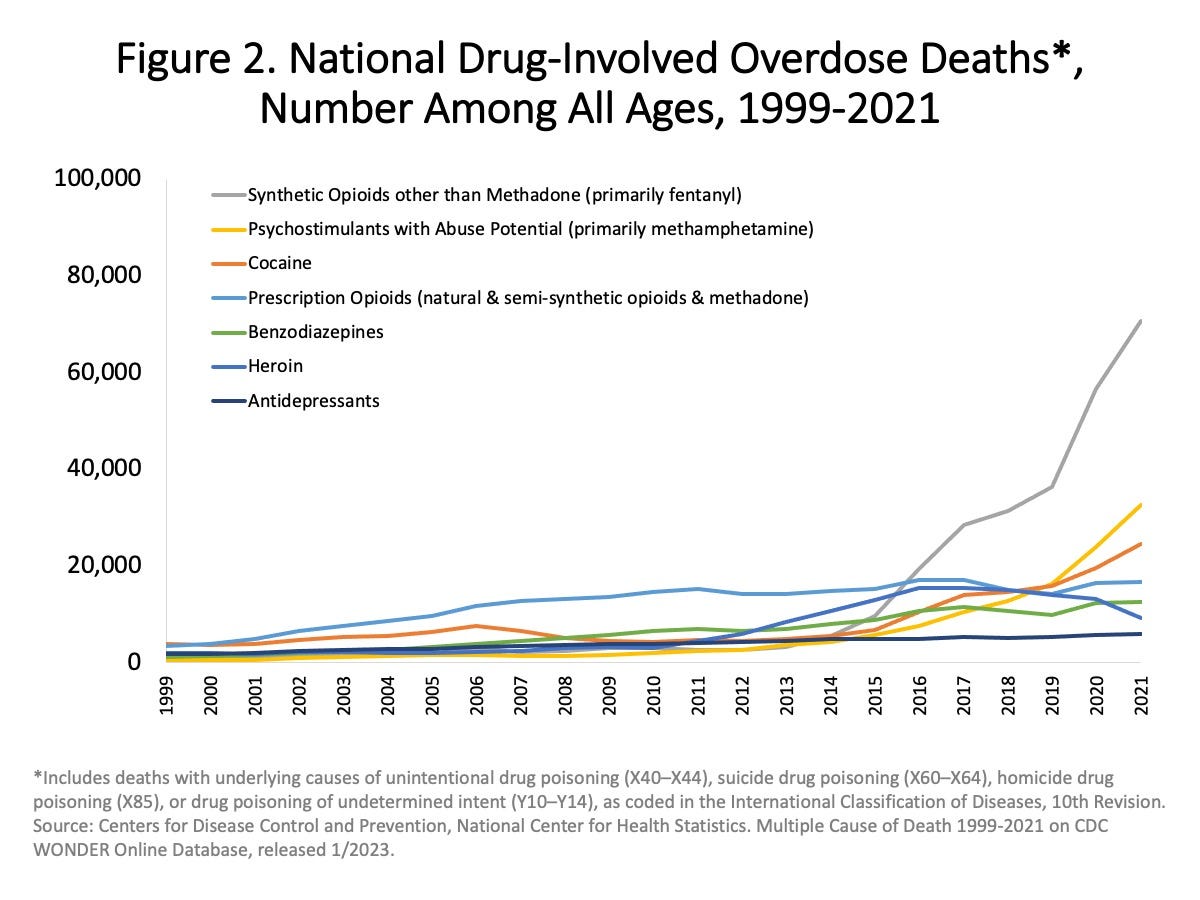

High lipophilicity, short half-life, high potency and poor cross-tolerance, frustrating attempts to switch to less harmful compounds. It is the most toxic in overdose of all the benzodiazepines.5 Xanax is present in 1 of 20 deaths by overdose.

Once the genie is out of the bottle—Xanax will help you forget your woes—it does not stop. Fake bars are fueling death. Xanax is so addictive that counterfeit drug makers use its branding. Why is a prescription drug a better “abuse brand” than street drugs?

In total, there were more than 54,000 overdose deaths, including 2,437 with evidence of counterfeit pill use. (CDC, 2019-2021)

Xanax is a pox upon the house of medicine, and Laurence Guttmacher, M.D. was eager to blowtorch his very well-reimbursed speaking career when he understood the truth.

Laurence Guttmacher, M.D., is an excellent teacher.

I know, I know. Look, I know.

benzodiazepines have amnestic effects, and that you will forget things. That amnestic part of drugs effect relies on the bz1 subunit of the GABA-A receptor.

Guttmacher's father was a psychiatrist who served as the defense expert medical witness for Jack Ruby when he was put on trial for the murder. He killed Lee Harvey Oswald, who shot Kennedy in the head.

I’ve never dispensed samples in my career on account of it.

Isbister GK, O'Regan L, Sibbritt D, Whyte IM. Alprazolam is relatively more toxic than other benzodiazepines in overdose. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004 Jul;58(1):88-95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02089.x. PMID: 15206998; PMCID: PMC1884537.