The Devices Are Coming! Depression Treated At-Home Without Meds?

A new publication begs the question: is this then end of psychopharmacology?

This newsletter has a perspective that is “fair and balanced.” Okay, that is a lie. The Frontier Psychiatrists barely tolerated less-than-effective oral medicines with painful adverse effect profiles. Heck, I wrote a whole book called Inessential Pharmacology (Amazon affiliate link) on the topic!

Our editorial point of view is that medical devices that modulate the brain will be the future. Unlike Elon Musk and his “it’s coming” drum beat—my car didn't’ drive itself to end my lease after all—the medical device scientists, despite headwinds, keep bringing new innovations to market and publishing groundbreaking papers. This week is no different. Nature Medicine—which, I'm told, is an important publication with an impact factor in 2023 is 58.7—just published a trial titled:

Home-based transcranial direct current stimulation treatment for major depressive disorder: a fully remote phase 2 randomized sham-controlled trial

I’m going to be honest: this should have spelled out an acronym, such as the following:

Home-based Evaluation of Active and sham Direct current stimulation for Treatment of Really Intolerable feels in Psychiatry

Or the HEAD-TRIP trial. That would have been punchier. Scientists, Chat-GPT exists. It’s not for writing papers but great for punchy titles. For simplicity— and my personal amusement—I’ll refer to this as the HEAD-TRIP trial throughout the rest of this article. Oh, wait. There was a snappy name. I had to go to clinicaltrials.gov to find it, but it was worth it:

The first question is, what did the scientists do? They used transcranial direct current stimulation to stimulate the brain. Direct current is like a 9-volt battery. Current flows in one direction from anode to cathode. The researchers position this low-current stimulator on humans’ heads as follows, and the current turns on and off at some frequency:

tDCS consisted of five sessions per week for 3 weeks, then three sessions per week for 7 weeks in a 10-week trial, followed by a 10-week open-label phase. Each session lasted 30 min;1

Some people got active, some got sham, and it wasn’t in a lab—they let people do it at home. For the Electrical Engineering enthusiasts at home, this power was in the milliamp range:

the anode was placed over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the cathode over the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (active tDCS 2 mA and sham tDCS 0 mA, with brief ramp up and down to mimic active stimulation.

That little ramp-up was to preserve the blind—it felt like an actual stimulation was coming, but it wasn’t. I will let us all hold our breath to find out if it worked to preserve the blinding!

I know what my readers are thinking. Come on, Muir, show us table one! This newsletter might as well be called “the table one star-tribune!” I won’t disappoint you:

There was one failure of randomization—the ethnicity was not the same between the groups—but again, by chance, we would expect some differences if we made enough comparisons. I doubt this invalidates the trial. However, regarding all other relevant details, the sham and active groups were not different. These were “depression patients”…with 4+ prior episodes on average…but as we will see, they were not the sickest of patients with depression.

They were less suicidal than average…their base rate was 0.1-0.16, and the best numbers we have previously are from Maria Oquendo’s work at Columbia:

…up to 80% of depressed individuals report suicidal thoughts, yet the lifetime risk of a nonfatal suicide attempt in major depressive disorder is estimated to be around 16%–40%2

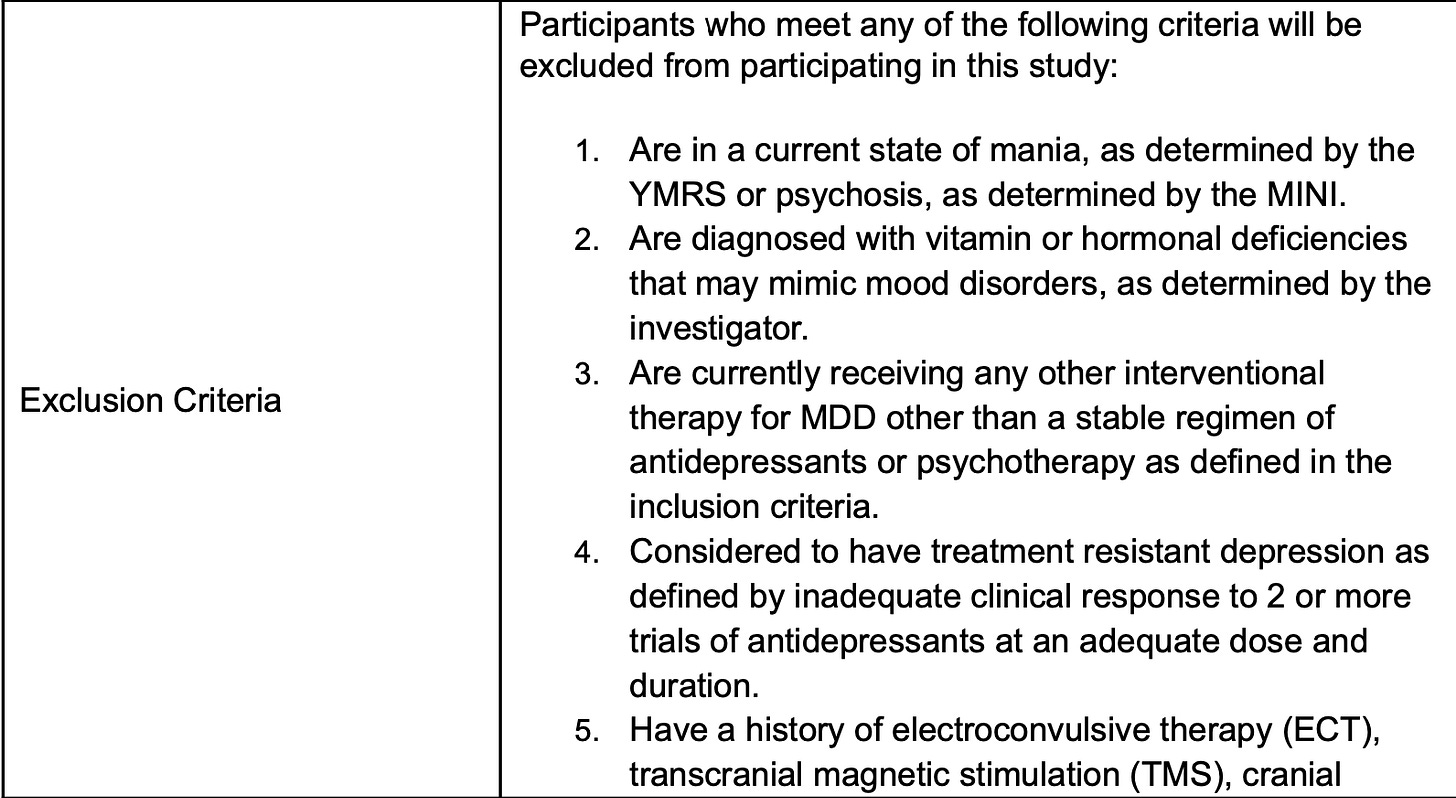

This isn’t particularly surprising for a depression study in which current SI is excluded. However, the paper itself mentions inclusion criteria only, and not exclusion criteria, so I had to dig into clincaltrial.gov and then the link to the actual study protocol another click-level below that…le sigh. But, dear readers, here it is:

For safety, not manic. Fine. They could never have gotten TMS or ECT….which makes sense for the ability not to bias results with more refractory patients but limits generalizability to the interventionists like your author, who will want to know if this worked in people when TMS didn’t. The exclusion criteria get more problematic from a “real world” perspective on the next page:

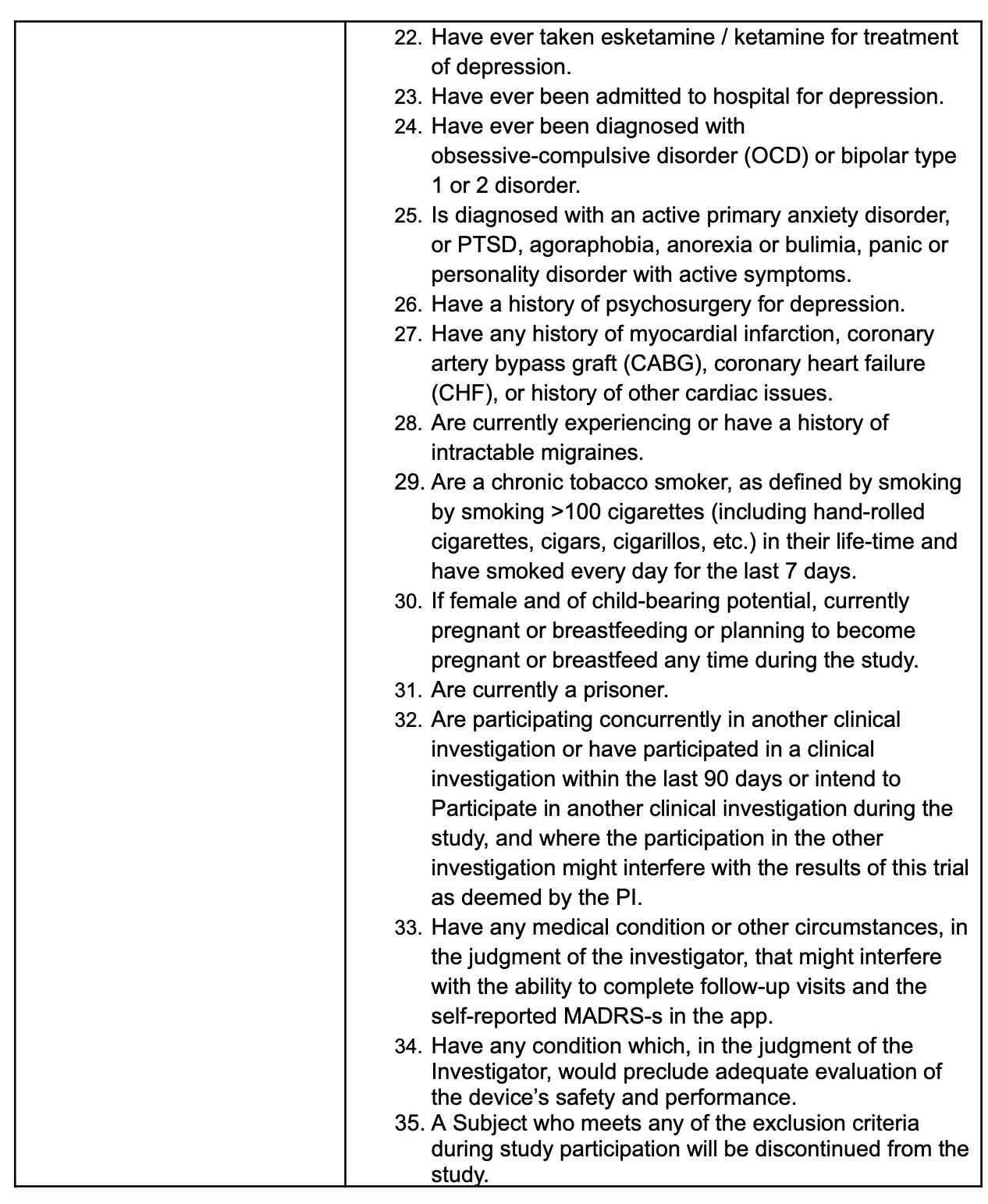

The trial ruled out those who had ketamine or esketamine, who had ever been in the psychiatric hospital, who had co-occurring OCD, who had ever had anyone think they had bipolar disorder, PTSD, an eating disorder, agoraphobia, a “primary” anxiety disorder, or have ever smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their life….or…

Or had any previous suicidality on the screener (which makes me wonder who the suicide attempters were?) given if any of the prior attempts landed them in the hospital, they were also excluded…or if they had epilepsy or autism, or take benzos…The point is that there are a lot of exclusion factors that don’t map onto clinical populations easily. We know this sample had depression—only— and kept their phone up to date as an inclusion criteria:

And they had a current psychiatrist who could keep an eye on things. Despite being an at-home trial, it probably doesn’t generalize to Medicaid populations easily, for example. It’s a study of people who can pull their act together to see a shrink regularly and not ever have been too suicidal or depressed or bipolar or ocd or traumatized or anything. And all of that is understandable if you want your trial to work. It also calls for subsequent trials to answer these questions for practicing clinicians if the device is approved.

This is a phase 2 trial. I'm not throwing shade at the trial design. I am advocating for the phase 3 trial and subsequent studies of this and other modalities to have broader inclusion and exclusion criteria.

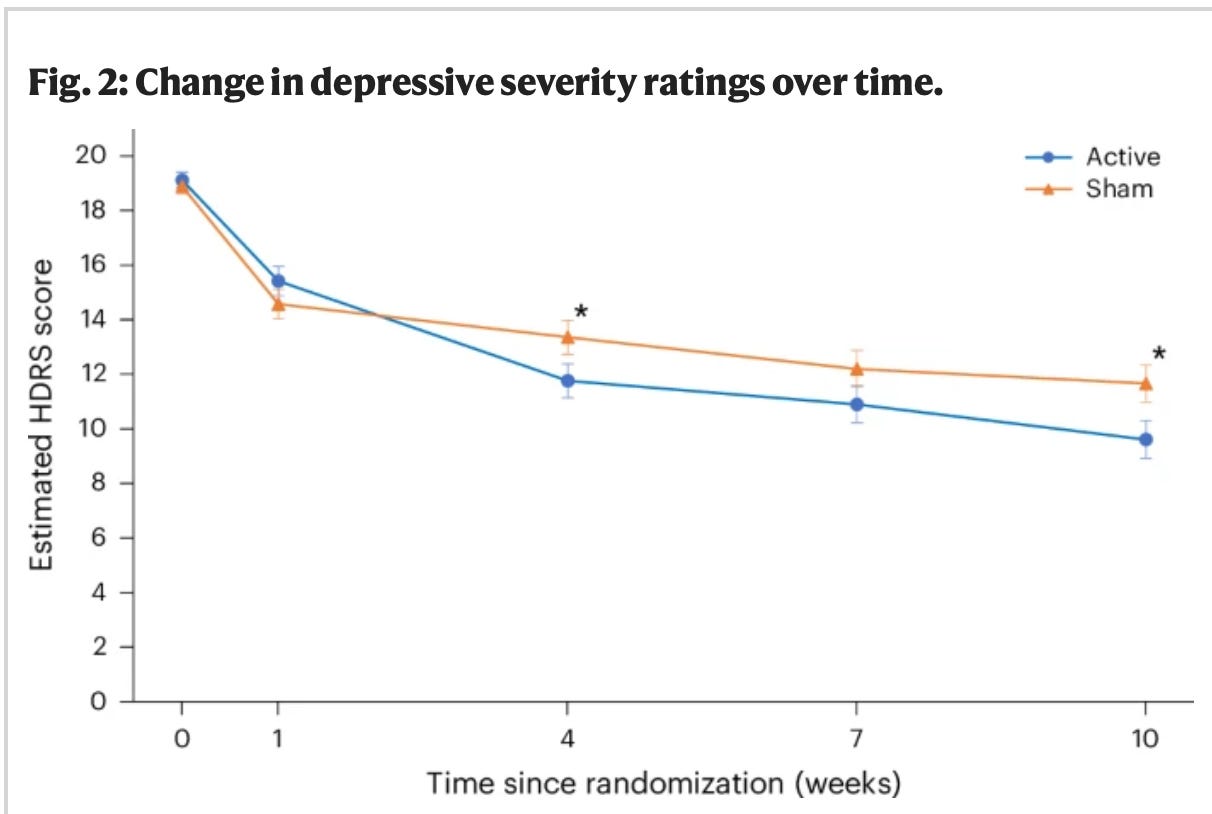

Moving on, in the very carefully selected population of depressed, but not scary, depressed patients studied, did this intervention work? In short, yes:

The active treatment group was statistically better than the sham group at the endpoint. More of them were in remission, too:

Based on the HDRS ratings, the active tDCS treatment arm was associated with a significantly greater clinical response of 58.3% compared to the sham treatment arm (37.8%; P = 0.017)… The active treatment arm was associated with a significantly greater remission rate of 44.9% relative to the sham treatment arm (21.8%; P = 0.004)

Similar, but not as bad as MDMA trials, functional unblinding was an issue:

Before unblinding at week 10 (end of trial), participants were asked to guess whether they thought they were receiving the active or sham tDCS … A guess of active tDCS was made by 77.6% in the active treatment arm and 59.3% in the sham treatment arm; the difference was significant (P = 0.01).

There were even honest to goodness adverse effects, like any active treatment:

At week 10, reports of skin redness ((active = 54 (63.5%); sham = 15 (18.5%), P < 0.001), skin irritation ((active = 6 (6.9%); sham = 0 (0%), P = 0.03) and trouble concentrating ((active = 12 (14.1%); sham = 3 (3.7%), P = 0.03) were greater in the active treatment arm relative to the sham treatment arm.

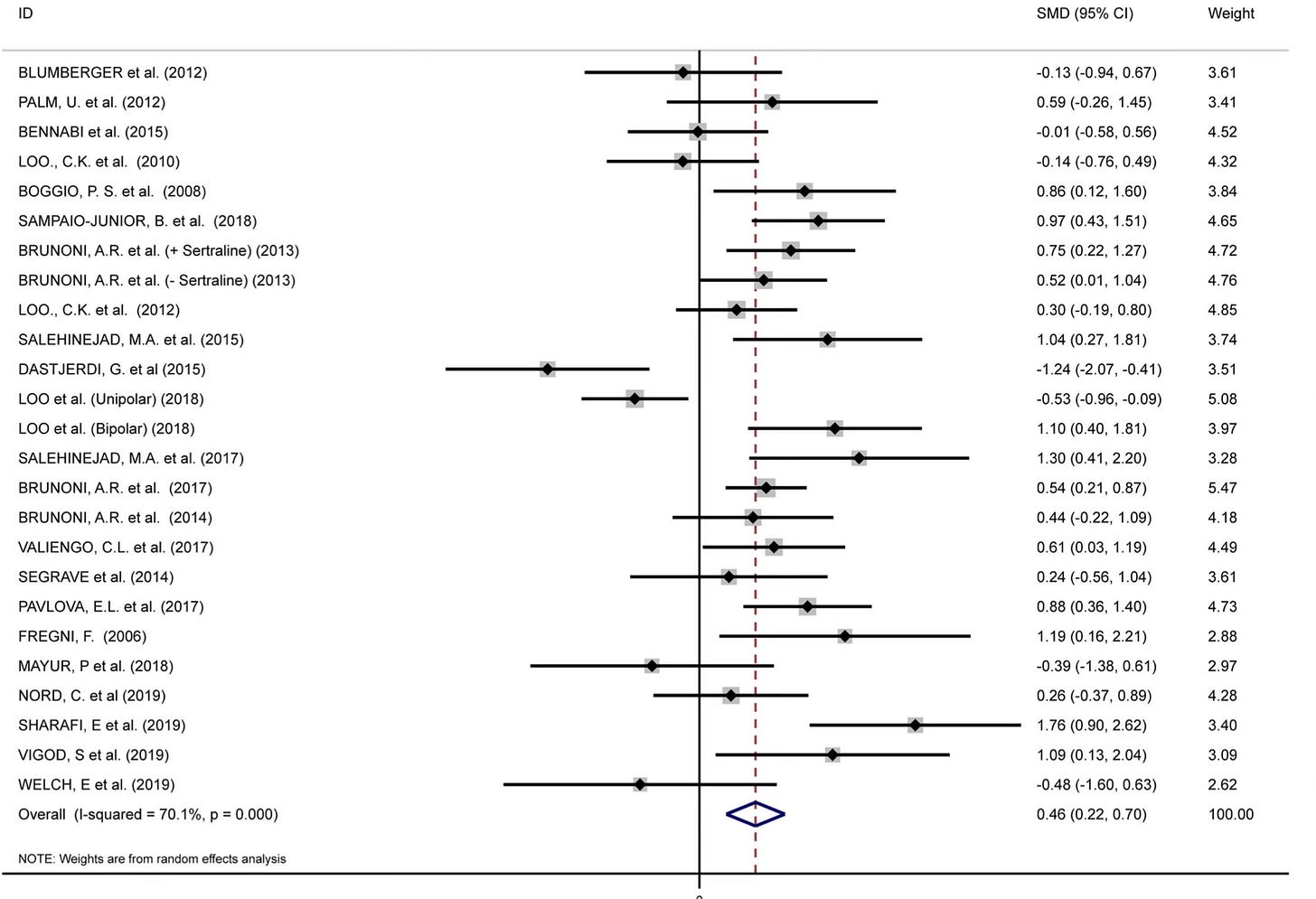

Adverse effects that would go a long way towards explaining how the active group could tell they were in the intervention group. The sham? It will need to be improved to preserve the blind in future trials! Regardless, this is a triumph for brain stimulation and tDCS specifically. decades of work on tDCS has struggled to demonstrate its consistent superiority in the treatment of depression compared to sham…with pooled analysis showing effect sizes that were passable at 0.46…

But with subject rated “acceptablity” not demonstrating people thought it was worth their time:

In short, it’s been a lot of study to understand that tDCS was capable of something, but required more work still to demonstrate superior outcomes in keeping with at-home use in a population of patients with depression.3

The HEAD-TRIP…sorry, EMPOWER trial demonstrated this is a viable treatment in a device people can put on their heads at home if they have just depression and not anything else.

It it “at home SAINT TMS?” No. It’s not. And we shouldn’t expect that from tDCS, based on prior studies. But if we are asking about first line treatment options for depression that can be expected to work, we no longer have to imagine that only oral medicines are the only option. The effect size here…0.37. If this were a treatment for height, it would add 0.925” to your height as an average american male using the Muir-Skee Lo EQE.

Flow Neuroscience got serious, large scale, home deployable, effective depression treatment to scale in a clincal trial that looks “real” to my eyes. That is a huge accomplishment. Their team should be commended. Now, all we need is some possible way to actually pay for depression treatment that isn’t a pill.

Woodham, R. D., Selvaraj, S., Lajmi, N., Hobday, H., Sheehan, G., Ghazi-Noori, A. R., ... & Fu, C. H. (2024). Home-based transcranial direct current stimulation treatment for major depressive disorder: a fully remote phase 2 randomized sham-controlled trial. Nature Medicine, 1-9.

Mareike Ernst, Lisa Kallenbach-Kaminski, Johannes Kaufhold, Alexa Negele, Ulrich Bahrke, Martin Hautzinger, Manfred E. Beutel, Marianne Leuzinger-Bohleber, Suicide attempts in chronically depressed individuals: What are the risk factors? Psychiatry Research, Volume 287, 2020, 112481, ISSN 0165-1781, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112481.

Razza, L. B., Palumbo, P., Moffa, A. H., Carvalho, A. F., Solmi, M., Loo, C. K., & Brunoni, A. R. (2020). A systematic review and meta‐analysis on the effects of transcranial direct current stimulation in depressive episodes. Depression and Anxiety, 37(7), 594-608.

Dr. Muir, your ability to continually outdo yourself, day after day, is remarkable and heroic