My favorite opening line of an academic article1 (this week) follows:

Mental illnesses are prevalent, cause great suffering, and are burdensome to society.

Welcome to the Frontier Psychiatrists. It’s a newsletter that I write all by myself. I’m doing a series on medications, largely (but not entirely) in psychiatry. I’m a child and adult psychiatrist, and I still see patients. I’ve also been a patient since I was 16 years old. Please consider subscribing and sharing widely.

The first antipsychotic introduced after clozapine would be a big deal—especially if it didn't cause life-threatening side effects. Risperidone was first developed by the Johnson & Johnson subsidiary Janssen-Cilag between 1988 and 1992 and was first approved by the FDA in 1994. It’s one of the very few drugs with data for bipolar disorder that I, personally, have never been prescribed.2

Risperidone—Risperdal as a trade name—was ready to be a huge hit.

It was presented as very atypical—this was the post-clozapine branding of choice. The “second generation” label was added years later. I have a confession to make. After residency, when the attending doctors told me, as a trainee, what to prescribe, I never prescribed risperidone ever again. I think this compound—and paliperidone, the metabolite— still has an important role in managing schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. There are more formulations of long-acting injectable risperidone and related compounds than I can remember. I think those are going to be useful drugs for a long time3. Oral risperidone? Nope.

Clozapine was an exciting drug. No horrible motor side effects? (Plausibly) More effective? It was better than every drug that came before. It had this pesky adverse effect that could lead to death called agranulocytosis4, which I addressed in my first research paper in 2011. We needed more drugs that were this atypical!

We—the field of psychiatry, at least— needed things that were not gonna kill you abruptly, in a terrifying manner, like clozapine had the rare potential to do. But we didn't want more of the same old antipsychotics. After Psychiatry got a taste of not having to explain permanent tardive dyskinesia as a likely side effect of antipsychotic medication, we wanted to keep doing that. Editors note: It is still a side effect of all non-clozapine antipsychotics, and we should never have let our guard down.

Risperidone was the first antipsychotic that came to market after clozapine rocked the world of psychiatry by being better. Risperidone is similar, and they even use the accidental branding of clozapine— “atypical”—for this medication.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved indications for oral risperidone (tablets, oral solution, and M-TABs) include the treatment of:

schizophrenia (in adults and children aged 13 and up),

bipolar I acute manic or mixed episodes as monotherapy (in adults and children aged 10 and up),

bipolar I acute manic or mixed episodes adjunctive with lithium or valproate (in adults)

autism-associated irritability (in children aged 5 and up).

Also, the long-acting risperidone injection has been approved for the use of schizophrenia and maintenance of bipolar disorder (as monotherapy or adjunctive to valproate or lithium) in adults.

The “mechanism of action” of all of the drugs that have efficacy in psychosis was presumed to be5 dopamine D2 receptor blockade6, a mechanism shared with all of the prior medication from Thorazine (chlorpromazine) through Haldol (haloperidol). The assumption—which clozapine disproved—was motor side effects were required for the drug's efficacy in psychosis. This primacy of the D2 blockade as a mechanism of action has since been disproven. This is the mechanism7 that leads to gynecomastia, leading to a bevy of lawsuits from men who developed breasts. It also causes related side effects like galactorrhea—breast milk from breasts that can be on men or women who are not nursing— and erectile dysfunction.

Dopamine—it does a lot of work in the brain, not just pleasure.

This motor side effect profile was not true with clozapine. It had various additional receptors, particularly in the serotonergic family (5HT-2a, for example), and alpha-adrenergic, histaminic, and other receptor sites throughout the brain.

This broad profile of different receptors explains the wide range of side effects. But more importantly, these are complex, “messy,” and hard-to-predict outcomes given the complexity of the brain. The complex pharmacology allowed psychiatrists like me to think—hard!—about which particular witches brew of receptors we would choose to tickle (agonize) or antagonize.8 It’s very satisfying. I also suspect this is a story we tell ourselves that is not as closely moored to truth as we’d like. We enjoy thinking about science-ish stuff. Receptor binding profiles are seductive— because they are knowable. Our patient’s heart, hope, dreams, and heartbreak? Less so.

The most important feature of risperidone today—and its 1st order metabolite, paliperidone9—is that is deliverable as pills, rapid-acting dissolvable tablets, and long-acting injectable formulations, lasting between 2 weeks and 6 months between doses.

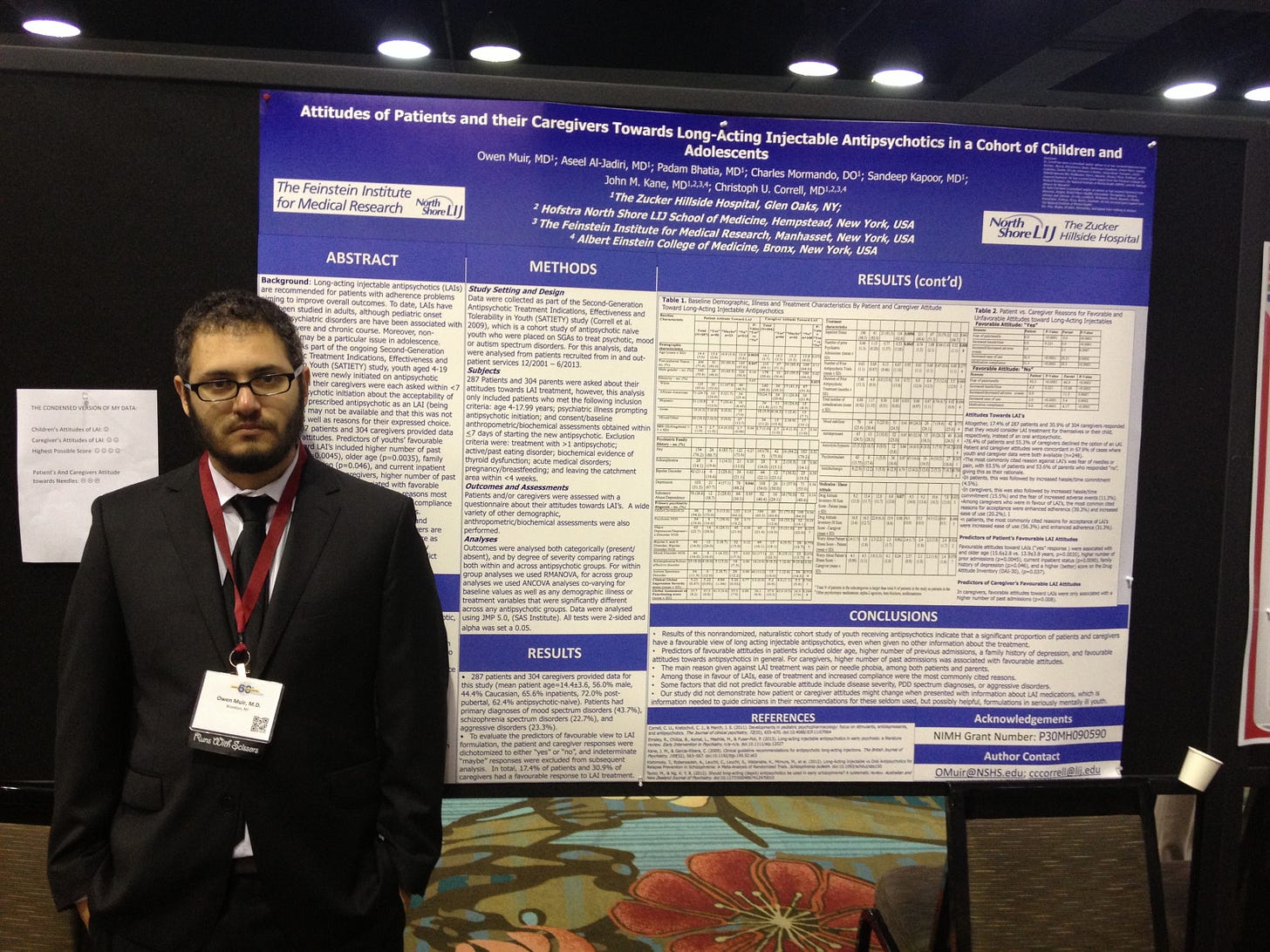

A psychiatric treatment that isn’t an oral once-daily pill? One you have to take twice a year? Medicine that is intended for people who often—like many—feel conflicted about taking a daily pill? That is a big enough deal. That is a real innovation— it considers human frailty, ambivalence, and common failures of mind. Not because it’s a magic drug. Rather, long-acting medicine that doesn’t make crippling relapse easy —thanks to good design— is exactly the kind of medicine that works. My second research effort was on the acceptability of such medicines in youth. It’s responsible for my presence at the academic conference10 where I met my now wife.

Oral medicines were popular because they were easy to sell. Novel medicines and technologies will be easy to take. The story of my fascination with the risks and benefits of these medicines doesn’t end there, though.

I still research these medicines and their adverse effects— funded by NIMH— for identifying Tardive Dyskinesia with Machine Learning and closed-loop Internet of Things physical medication compliance tech with my team at iRxReminder and colleagues at Videra. We are enrolling in a study at Fermata in New York and other sites.

Thanks for reading.

This article is another in my series about one drug or another. Prior installments include Depakote, Geodon, Ambien, Prozac, Xanax, Klonopin, Lurasidone, Olanzapine, Zulranolone, Benzos, Caffeine, Semeglutide, Lamotrigine, Cocaine, Xylazine, Lithium, dextromethorphan/bupropion and Adderall, etc.

Sponsored Content!

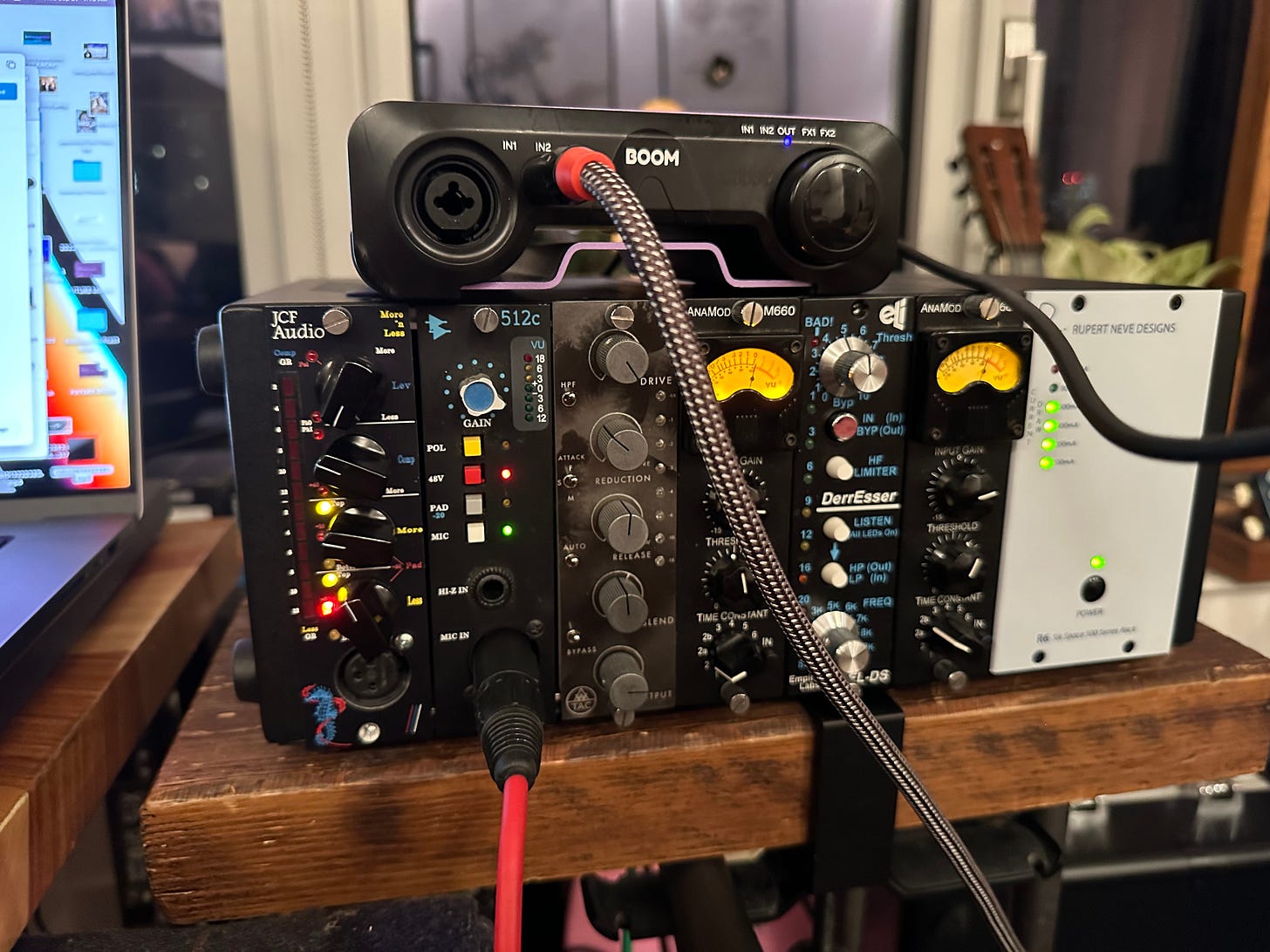

One way of supporting this publication is buying stuff from Amazon, like a nifty box from Apogee that I used to record the voice-over: the BOOM. In fairness, it’s just the A/D. I am also using the API 512c mic pre, plugged into an AnaMod 660 500 series compressor, nestled in a reliable RND R6 Lunchbox, and all of that plugs into the Boom into my Mac. It’s a Microtech Geffel mic. Most of the audio post-processing is done with Izotope RX 10. I get money if you purchase any of these things— not a trivial amount since they upped my affiliate rewards.

In case anyone was wondering if I was an audio nerd…

Laura Weiss Roberts, Cynthia M.A Geppert, Ethical use of long-acting medications in the treatment of severe and persistent mental illnesses, Comprehensive Psychiatry, Volume 45, Issue 3, 2004, Pages 161-167, ISSN 0010-440X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.02.003.

I have been treated, over many years, with olanzapine, aripiprazole, asenapine, ziprasidone, quetiapine, lithium, carbamazepine, cariprazine, Divalproex, oxcarbazepine, fluoxetine, sertraline, alprazolam, diazepam, pramipexole, lorazepam, eszipoloclone, bupropion, trazodone, modafinil, dextroamphetamine/amphetamine, lamotrigine, dexmethylphenidate, and that is just off the top of my head and just for psychiatric indications. I’ve been through the wringer, I think it’s fair to say.

Ironic when referring to Long-Acting Injectable medicines.

Manu P, Sarpal D, Muir O, Kane JM, Correll CU. When can patients with potentially life-threatening adverse effects be rechallenged with clozapine? A systematic review of the published literature. Schizophr Res. 2012 Feb;134(2-3):180-6. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.10.014. Epub 2011 Nov 22. PMID: 22113154; PMCID: PMC3318984.

Yun, S., Yang, B., Anair, J. D., Martin, M. M., Fleps, S. W., Pamukcu, A., Yeh, N., Contractor, A., Kennedy, A., & Parker, J. G. (2023). Antipsychotic drug efficacy correlates with the modulation of D1 rather than D2 receptor-expressing striatal projection neurons. Nature Neuroscience, 26(8), 1417-1428. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-023-01390-9

Meltzer HY, Gadaleta E. Contrasting Typical and Atypical Antipsychotic Drugs. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2021 Jan;19(1):3-13.

in the tuberoinfindibular dopamine pathway, one of the less cool dopamine tracts, but in this brain system dopamine inhibits the release of prolactin from the pituitary. Thus dopamine blockers lead to prolactin release, and thus lactation, among other things.

Side effects include orthostatic hypotension, dose-dependent risk for motor side effects, which increase first-generation medication levels at doses above 4 mg, and even tardive dyskinesia. Weight gain, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome are also common.

paliperidone is what your liver gives you when you take risperidone after the first pass of liver metabolism. The enzyme responsible is cytochrome p450 2D6, which is highly variable in Caucasians but homogeneous in Han Chinese populations. This is important when you review research data on clinical trials run in different parts of the world. China will have different response profiles on 2d6 drugs than northern Europe, where 20% will have wildly different metabolism of the same drugs!

Correll, C. U., Muir, O., Al-Jadiri, A., Kapoor, S., Carella, M., Sheridan, E., ... & Kane, J. (2013, December). Attitudes of Children and Adolescents and Their Caregivers Towards Long-acting Injectable Antipsychotics in a Cohort of Youth Initiating Oral Antipsychotic Treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology, 38, S280-S280.