Prazosin

It's a drug for nightmares.

The Frontier Psychiatrists is a daily-enough health-themed newsletter. With the advent of the recent FDA AdComm meeting about MDMA-AT, I've been doing a lot of writing on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and pharmacological interventions. It's time we flashback—sorry—to a time before all these promising, psychedelic medicines were seemingly on the precipice of bringing relief. I'm going to remind us that there are existing treatments for PTSD symptoms, and one of them is called prazosin. A teaser of a pull quote, you wish you had? Granted:

Because α1-adrenergic activity has been associated with fear and startle responses, a drug that blocks central α1-adrenergic activity may be useful in the treatment of PTSD symptoms.

First, a brief review of the grim data for other medications.

Other Drugs For PTSD

Medication for post-traumatic stress disorder has performed extremely poorly in large-scale samples. Only Sertraline and Paroxetine have FDA labels for PTSD treatment, but subsequent reviews by the Cochrane Group have called the data supporting those treatments into question at a larger scale.1. SSRIs work a little bit:

Ok For the primary outcome of treatment response, we found evidence of beneficial effect for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) compared with placebo (risk ratio (RR) 0.66…8 studies, 1078 participants…which improved PTSD symptoms in 58% of SSRI participants compared with 35% of placebo participants, based on moderate‐certainty evidence.

Improved but still suffering, about 23% more study participants got “improvement” on the drugs. But they are also sometimes harmful:

For the outcome of treatment withdrawal, we found evidence of a harm for the individual SSRI agents compared with placebo (RR 1.41, 14 studies, 2399 participants). Withdrawals were also higher for the separate SSRI paroxetine group compared to the placebo group ….The absolute proportion of individuals dropping out from treatment due to adverse events in the SSRI groups was low (9%), based on moderate‐certainty evidence.

So the FDA-approved drug, paroxetine, was also the most harmful and withdrawal.

It's worth noting that there was a recent Cochrane review in 2022 on the prevention of PTSD after trauma exposure with pharmacotherapy. Bad News Incoming: nothing worked.2

This review provides uncertain evidence only regarding the use of hydrocortisone, propranolol, dexamethasone, omega‐3 fatty acids, gabapentin, paroxetine, PulmoCare formula, Oxepa formula, or 5‐hydroxytryptophan as universal PTSD prevention strategies.

We have a scenario where older medications exit. Nobody's going to make any money if they get an FDA label—they are already generic. Those FDA labels can cost billions of dollars. A study sponsor has to run clinical trials and Shepard the drug through a regulatory process.

We have a raft of older medications, and prazosin, the topic of today's article, is one of those…might it help?

This financial issue was a problem that MAPS/Lykos was trying to “fix” with the combination product of MDMA-AT; by the way—the drug is off-patent, but the new combination with therapy, in theory, wasn’t.

For those interested in my prior articles on this disaster of a regulatory process, see the following articles:

Can MDMA-AT Be Saved, Part I, Can MDMA-AT Be Saved, Part II, Should MDMA-AT Be Saved, Part III, Saving MDMA from AT: Part IV, Bad Touch!: MDMA Part V, Saving MDMA (and other psychedelic therapies), Part VI.

One could argue that creating an entirely new untested therapy just to get a drug over the line with the FDA doesn't make much sense, and I would tend to agree with whoever was making that argument. We might need a different mechanism to determine if drugs are worth studying that can’t make a bazillion dollars. To be clear, this problem only gets worse with time. There are many chemicals that we never got around to turning into pharmacologic treatments, and have they been on the shelf too long? Game over.

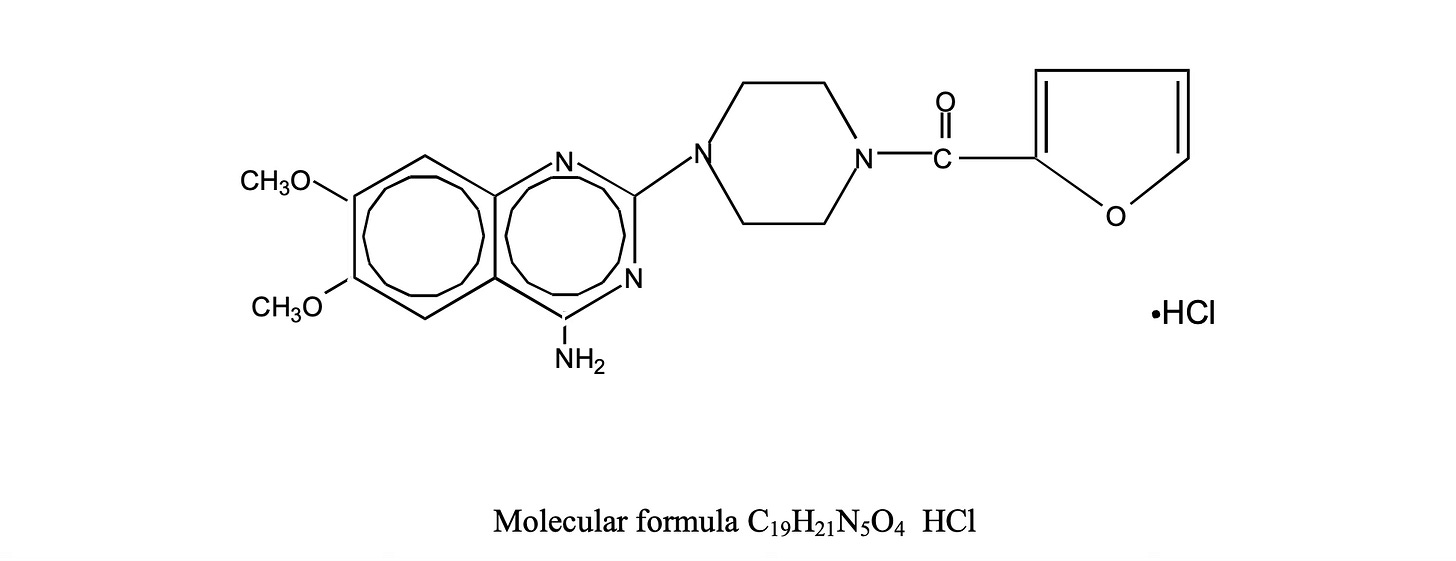

One such drug has it’s FDA approval for…hypertension. Brand name: “Minipress.” It was approved by the FDA in 1988 as a blood pressure medicine.

The drug works as an alpha-one adrenergic antagonist. For general audiences, some explaining. You're about to learn about the regulation of blood pressure. Sexy, I know.

You've heard of epinephrine and norepinephrine, or perhaps adrenaline and noradrenaline; these are the same. Epinephrine is the American name, and the British name is adrenaline. Hormones work in the periphery; neurotransmitters work in the central nervous system. This is a vast oversimplification. her blood pressure is regulated by a combination of how fast our hearts beat, how much blood comes out of that heart, and then how wide her blood vessels are at any given point in time.

We have arteries that change diameter and veins which don’t. The arteries are before our organs, and the veins are after. Arteries carry blood from the heart to the organs. Veins carry blood back to the heart. So, let's imagine we need to run away from a tiger. This can save our lives. But to do so, we need to move our bones. What is the muscle tissue that moves our bones? This is called skeletal muscle. Those muscles take up a lot of oxygen to move very fast. And a very fast-moving body—muscles, bones, and all, is what you need to run away from a tiger.

Skeletal muscle needs oxygenated blood to function at its peak efficiency, but we don't want our blood constantly dedicated to muscle all the time, because sometimes we need to rest. And that, it turns out, takes blood also. We constantly decide, as organisms, whether blood should go to the gut so we can digest more efficiently or to our skeletal muscles and brain so we can get out of trouble.

That regulatory dance is addressed by deciding where the blood goes. For that, we need smooth muscle, which makes up our blood vessels. If the diameter of the arteries gets larger before the muscles? More blood will go there. But it turns out that if our blood vessels are a little too tight all the time, our blood pressure goes up. We're trying to maintain homeostasis, staying roughly “in the middle” as an organism. And that's a delicate dance. Hypertension is a condition where our blood pressure goes up too much because this regulatory mechanism between how much blood you have, how much it comes out of your heart, and how tight your arteries are at any given time gets out of whack.

Anti-hypertensive medications often work by helping you pee out more water, which reduces the total amount of blood and decreases your blood pressure. This class is called diuretics. Prazosin was a novel approach that was developed, and it changed blood vessel diameter. Norepinephrine is the neurotransmitter/hormone team that tells blood vessels to tighten up and increase our blood pressure—blocking the receptors on those blood vessels. In the peripheral vascular, these binding sites are called alpha receptors, specifically alpha-1. That was one way of dropping blood pressure. It also relaxes smooth muscle. That regulates micturition also! Prazosin can also be useful if you have trouble peeing, which men, as they get older, tend to need help with as prostates enlarge, pinching off the flow of urine from the bladder. Getting older? Grim business, indeed.

Ok, so that is what prazosin was originally for. However, evidence started to mount that this alpha-1 receptor wasn’t just on smooth muscle but in the brain. People treated with prazosin had fewer nightmares…so given many of those were military veterans, some money was able to be spared for clinical trials from the VA. A recent review summarizes the range of research:

Our search yielded 21 studies, [including] 4 RCTs, 4 open-label studies, 4 retrospective chart reviews, and 9 single case reports. The prazosin dose ranged from 1 to 16 mg/d.3

That is a lot of studies! The first study by Raskind et al. In 2003, significant results were achieved in the reduction of nightmares in 10 veterans4—which is hard to do in small samples but requires replication. Raskind, in a follow-up paper, noted:

Many of these subjects reported anecdotally that long absent “normal” dreams returned when trauma nightmares were reduced or eliminated during prazosin treatment and that symptoms of depression had decreased.5

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Frontier Psychiatrists to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.