Is My ADHD Medication Killing Me?

Tackling epidemiological data on the cardiovascular disease risks of ADHD treatment.

The Frontier Psychiatrists is on the beat of breaking news in science…as long as it happened over a year ago …and Owen is just getting around to reading it. The actual title of this article is a bit misleading — I am not currently taking any ADHD medication. A more accurate title might have been “Is Your ADHD Medication Killing You?” Both would be fundamentally misleading questions because case-control studies can't prove causation. This research is new and has not been covered in Inessential Pharmacology. (my book and an Amazon link).

Onward to today's paper, we are learning to read—together! On November 20, 2023, JAMA Psychiatry published the following massive epidemiological article1:

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Medications and Long-Term Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases

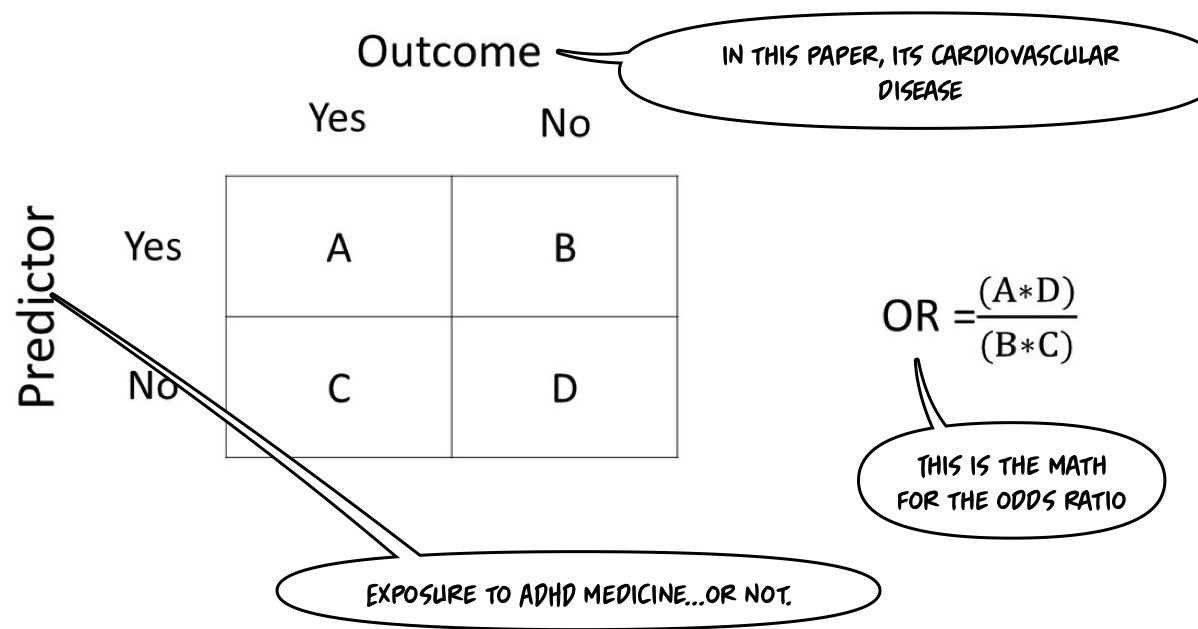

No matter what is demonstrated in the subsequent analysis, that title is Clickbait if I ever saw one! This is an article about risk. In epidemiology, we'll use the concept of an “odds ratio.” This paper is a “nested case-control” study design. It will be helpful to review basic observational study designs, at this point:

Cohort Studies involve following a group of individuals (the cohort) over time to observe outcomes. At the beginning of the study, participants are selected based on their exposure status (exposed vs. unexposed), and outcomes are compared between these groups. These are typically prospective in the time frame. They can also be retrospective if historical data are used.

In Case-Control Studies, on the other hand, participants are selected based on their outcome status (cases with the illness vs. controls without the illness). The study then looks backward to assess exposure status. They are Retrospective— authors know who got sick and who didn’t when they sit down to write the paper; what they are solving for is the degree of exposure.

This paper uses a Nested Case-Control design, a variation of a case-control study conducted within a defined cohort. Cases of a particular outcome are identified within the cohort, and for each case, a set of matched controls (who have not developed the outcome) is selected from the same cohort. This design allows adjustments to reduce the potential for selection bias since cases and controls are drawn from the same cohort.

The authors want to find out if more ADHD medicine leads to more cardiovascular diseases. However—diseases (plural) are not all the same.

Since we are following individuals after (variable) exposure over time but not randomizing them to one group or another, the study design cannot determine causality the same way randomized control trials can. However, when we're talking about risk to human health, it would be unethical to randomly assign people things that were understood to be risky to determine the risk. I’ve previously written about the lack of ethics in studies on parachutes vs. sham parachutes.

I quickly reviewed the math for odds ratios to find my readers the best graphic to illustrate the math.

This paper uses what they call adjusted odds ratios (AOR)—unless you're a more sophisticated statistician than myself, you have to trust that their adjustments are accurate. These adjustments are used to control for other variables, giving you a more accurate sense of the actual ratio that you could compare to other papers where the calculation was much less confounded.

The 30,000-foot view level result is as follows…

Findings In this case-control study of 278,027 individuals in Sweden aged 6 to 64 years who had an incident ADHD diagnosis or ADHD medication dispensation, longer cumulative duration of ADHD medication use was associated with an increased risk of Cardiovascular Disease (CVD), particularly hypertension and arterial disease, compared with nonuse.

Well, that is quite a finding! However, it probably matters for us to work out “which ADHD medicine” and “how much exposure is safe?” along with “Is the risk different in children versus adults?” “Are all ADHD medicines the same, or are they different?” Let's break this down together! This will be fun!

In this kind of study, everybody has some degree of exposure. So, 100% of people in the study had a diagnosis of ADHD or a prescription for ADHD medicine, which they can track in their national scale database:

Baseline (i.e., cohort entry) was defined as the date of the incident with ADHD diagnosis or ADHD medication dispensation, whichever came first.

Who is in The Sample?

Design, Setting, and Participants This case-control study included individuals in Sweden aged 6 to 64 years who received an incident diagnosis of ADHD or ADHD medication dispensation between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2020. Data on ADHD and Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) diagnoses and ADHD medication dispensation were obtained from the Swedish National Inpatient Register and the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register, respectively.

What counted as cardiovascular disease ranged widely, in keeping with the different severity of hypertension compared to heart failure and heart attack:

Cases included individuals with ADHD and an incident CVD diagnosis (ischemic heart diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, hypertension, heart failure, arrhythmias, thromboembolic disease, arterial disease, and other forms of heart disease). Incidence density sampling was used to match cases with up to 5 controls without CVD based on age, sex, and calendar time. Cases and controls had the same duration of follow-up.

I hadn’t heard of incidence density sampling before, either. Here is a paper explaining its role in nested case-control studies if you are really, really interested. It is, apparently, “a very efficient approach to an epidemiological investigation.”

The age range is broad:

We conducted a nested case-control study of all individuals residing in Sweden aged 6 to 64 years who received an incident diagnosis of ADHD or ADHD medication dispensation between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2020.

And followed them till an endpoint occurred:

The cohort was followed until the case index date (i.e., the date of CVD diagnosis), death, migration, or the study end date (December 31, 2020), whichever came first.

The authors ruled out some individuals from the cohort they followed over time:

Individuals with ADHD medication prescriptions for indications other than ADHD and individuals who emigrated, died, or had a history of CVD before baseline were excluded from the study.

So, narcolepsy, binge eating disorder, Hypertension (clonidine!), and other conditions that will lead to the prescribing of ADHD medicine were not included. Neither were people who already had CVD or moved away so that we wouldn’t know the outcomes secondary to a deprived life (from a data standpoint) in a less epidemiologically sound country.

What Was The Exposure?

The authors were attempting to determine the relationship between “how much ADHD medicine exposure” and the bad outcome in question, CVD:

The main exposure was the cumulative duration of ADHD medication use, which included all ADHD medications approved in Sweden during the study period, including stimulants (methylphenidate, amphetamine, dexamphetamine, and lisdexamfetamine) as well as non-stimulants (atomoxetine and guanfacine).

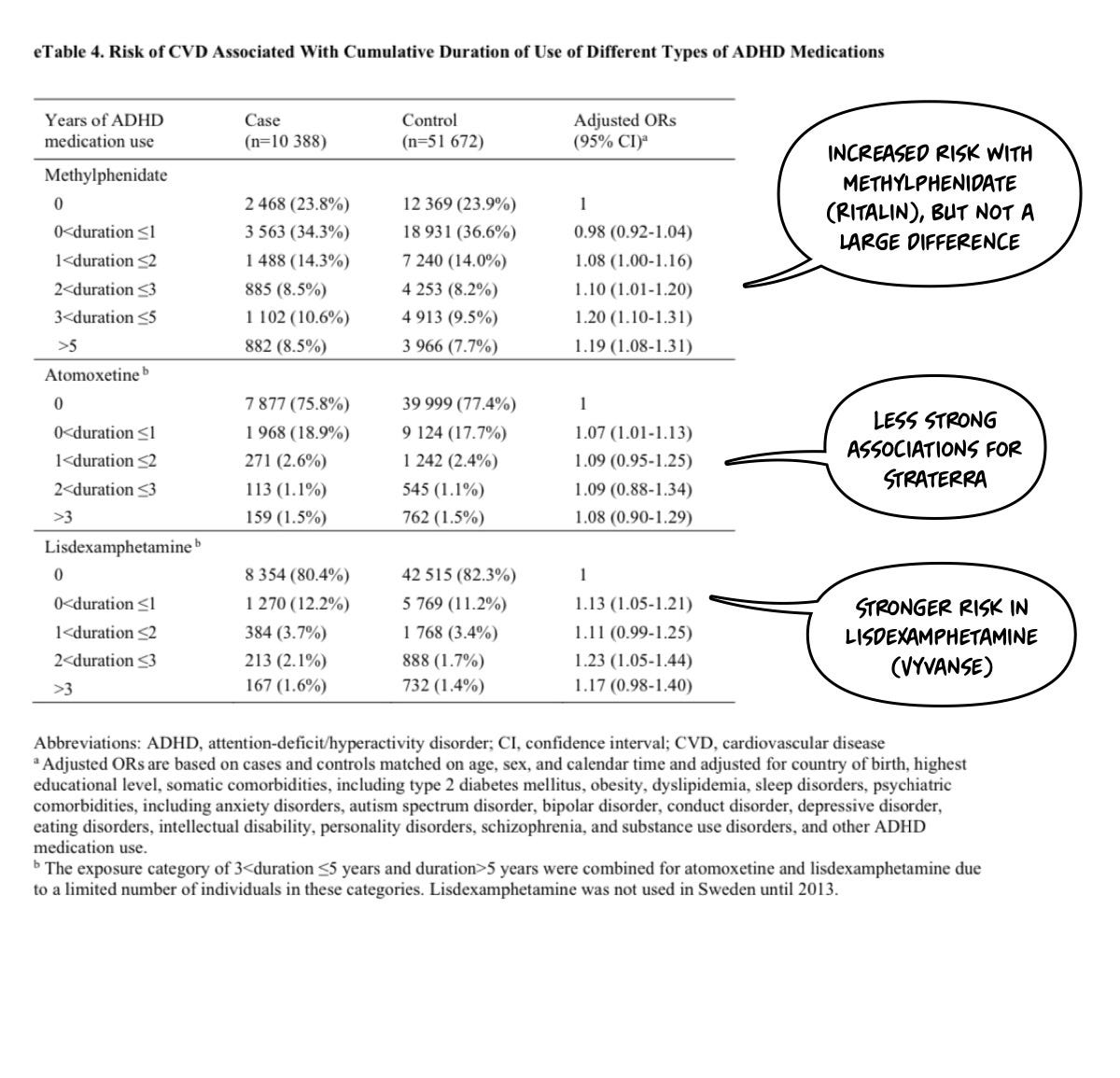

I’ll point out that I think this is a bad study design—a priori—because my pre-test suspicion is that neither guanfacine nor atomoxetine would increase blood pressure (for example). Thus, their inclusion will water down the results when lumped in. However, that is an empirical question that is only lightly addressed in the paper. You need to look at the supplemental materials:

What Was The Risk Profile?

Higher risk was seen in women at longer exposure time frames: