fMRI-Guided rTMS Doesn't Work For Everything

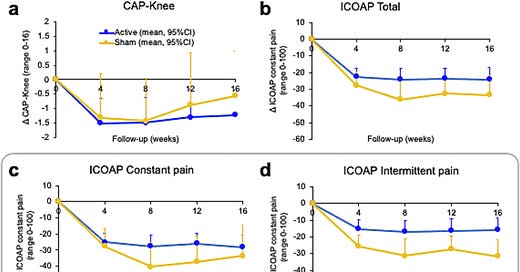

A new randomized controlled trial for osteoarthritis knee pain shows no difference from sham treatment.

The difference between science and non-science is that science is falsifiable. I love falsifiable hypotheses. Treatments that always work aren't real treatments. In today's quick dispatch, in keeping with my prior articles about how to read articles, we will review a negative trial.1

Accelerated intermittent theta burst transcranial magnetic stimulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex for chronic knee osteoarthritis pain

What's a negative trial? It's a study in which the hypothesized intervention didn't do any better than the “placebo” (in the case of device or instrumentation trials, we are for that as a sham, not a placebo).

This newsletter covers neuromodulation because it's a personal area of enthusiasm. But it doesn't work all the time, and it doesn't work for everything. Today, additional data demonstrates that doing an extremely fancy fMRI-guided brain stimulation is not the right approach for knee pain. For those inclined to yell, “I could've told you that,” well, sure, but it's not science until you prove it.

We already know that aiTBS—a pattern of multiple “theta-burst” treatments with transcranial magnetic stimulation is effective in depression. It's the basis of SAINT neuromodulation, for example. We even have one FDA-cleared approach for peripheral pain management with neuromodulation, a protocol developed by colleagues at MagVenture. So this isn't totally crazy. We also know that osteoarthritis, as a source of pain, is a real problem. Most people who have osteoarthritis pain don't get a joint replacement, which is the definitive treatment for that sort of pain.

Only 18%–30% with OA undergo total knee replacement in their lifetime2

Direct high-frequency motor cortex stimulation has also been recommended, with level A evidence3, which is substantial. Keep in mind that the oral medication we have for pain either causes serious side effects or can cause life-ending dependence.

Given SAINT's success in depression, the authors took a similar approach to functional connectivity: guided accelerated transcranial magnetic stimulation using the same intermittent and iTBS pattern.

The dosing was lower than used in depression, which is worth recalling because it's possible that they just underdosed the treatment:

Accelerated iTBS intervention was delivered over 4 days (V2-V5) each day consisting of 5 blocks (B1-B5) of stimulation (1800 pulses per block, 9000 pulses per visit/day, 36000 pulses in total/treatment week).

They also used a different functional connectivity target from that used in prior depression trials, in this case:

The optimal site was defined as the peak voxel within the lDLPFC receiving maximal effective connectivity from the right anterior insula (rAI; 6mm sphere centred on MNI voxel coordinates [x=30, y=24, z=-14]), abbreviated as rAI-connected lDLPFC (or rAIc-lDLPFC).

I can't tell you if this is the best site to use. I'm not an expert. One of the problems with reading this kind of paper is that you do benefit from being an expert in everything they're going to talk about to evaluate whether what they're doing makes any sense. And unfortunately, no one can be an expert in everything. I lack the expertise to answer, “Is the optimal connectivity site targeted reasonable for the outcome they sought?”