I did a “take” on the following study as a podcast recently. This is not a transcript of that podcast. I just this moment realized…I haven't edited it together yet. I guess that is next. For now, since I’m on a plan, welcome to an old-fashioned article typed with my fingers.

I start 95% of what you read on The Frontier Psychiatrists as dictation into Siri, because I find typing so aversive.

Not today!

Antisocial personality disorder (ASPD)—the least sympathetic of disorders. The criteria sound like a description of a terrible person, not a disease state (quoting the DSM-5 criteria):

A. Disregard for and violation of others rights since age 15, as indicated by one of the seven sub-features:

Failure to obey laws and norms by engaging in behavior which results in criminal arrest, or would warrant criminal arrest

Lying, deception, and manipulation, for profit or self-amusement,

Impulsive behavior

Irritability and aggression, manifested as frequently assaults others, or engages in fighting

Blatantly disregards safety of self and others,

A pattern of irresponsibility and

Lack of remorse for actions (American Psychiatric Association, 2013)

The other diagnostic Criterion are:

B. The person is at least age 18,

C. Conduct disorder was present by history before age 15

D. and the antisocial behavior does not occur in the context of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013)

If you are interested, it has evolved as a diagnosis between DSM-IV and DSM-5. It has the defining feature, as do all disorders, of causing distress…not just to the rest of us (“assaults of others!?”—that is us!). But if it’s a disorder, there should be a treatment. There wasn’t one, until now.

As an aside, not all psychiatric problems, especially personality disorders, present in people who are sympathetic or nice, or whom we’d want to help. Many deeply unpleasant people are both suffering and causing suffering to others in their lives. And, the point of the study I’m going to present, and much of my work, is that being nice or sympathetic shouldn’t be a prerequisite for believing everyone deserves help.

The benefit, that I believe to be the case, of helping the most unpleasant people—those who might even have ASPD—is that we can reduce suffering. Not just for sympathetic people, but for the many people that predatory and/or deeply unkind people might cause. If we can help people become less destructive, that is great for everyone. Fewer victims! Less trauma, for everyone. We should want to help the violent become less violent, so there will be fewer victims. It does require helping and directing resources towards unsympathetic characters.

Getting off that soapbox, I’m moving on to describe the most important study you’ve ever heard of. We have a treatment that helps violent offenders be less violent.

It is not a pill. It’s not an infusion. It is not TMS. I know.

It’s a psychotherapy. And now, we have not just a treatment manual (Amazon affiliate link) we have a randomized controlled trial. The modality is called “Mentalization-Based Treatment, (MBT)” and yes, your author, Owen Muir, M.D., is an official supervisor in MBT through the Anna Freud Centre for Children and Families. This therapy was developed by Anthony Bateman and Peter Fonagy, with initial data in Borderline Personality Disorder. I even co-wrote a book on the adolescent implementation of MBT. (Amazon affiliate link).

Prior articles? Yes. Use the search function, people.

It is mostly a group therapy. Yes, I know. Let’s break down the study:

Mentalization-based treatment for antisocial personality disorder in male offenders on community probation in England and Wales (Mentalizing for Offending Adult Males, MOAM): a randomised controlled trial

The authors randomized men who were violent offenders in England and Wales:

Participants were male offenders under National Probation Service supervision at 13 sites, identified through the Community Personality Disorder Pathways Service, aged 21 or over, meeting DSM-5 criteria for ASPD and scoring at least 15 on the Overt Aggression Scale Modified (OAS-M).1

Not just violent offenders on probation, but sufficiently violent ones, according to a rating scale…it’s available here. It is summarized below:

They provided informed consent and were randomized to either “probation as usual (PAU)” or this treatment, MBT-ASPD, which consisted of once weekly 50-minute individual MBT therapy and once weekly 75-minute group therapy sessions.

It was mind-bogglingly successful:

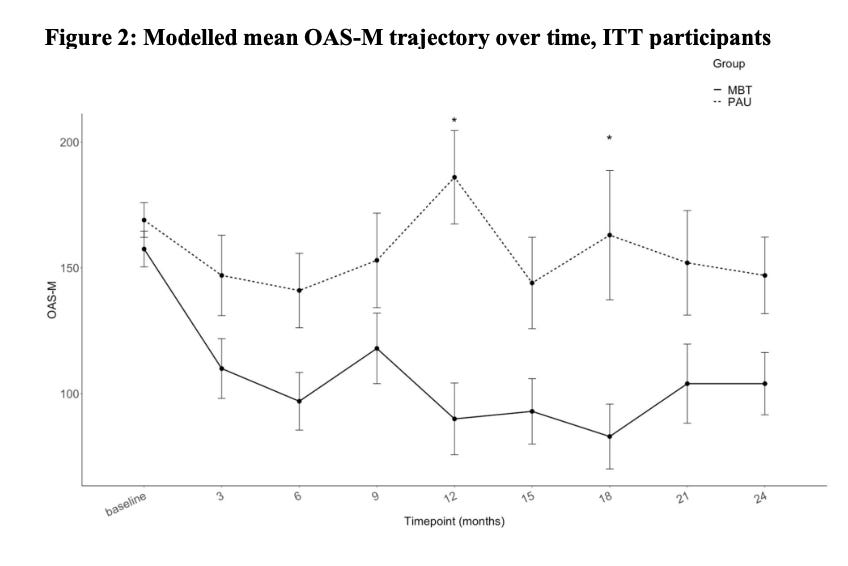

At 12 months post-randomisation, mean OAS-M scores were significantly higher in PAU (M=186) than MBT-ASPD (M=90) (adjusted mean difference between groups: –73.5, 95% CI –113.7 to –33.2; p<0.0001) with a medium to large effect size (Effect size=0.74) .

That effect size is huge—it’s on par with bona fide treatments like lithium in bipolar mania, and it’s bigger than oral antidepressants in depression, bigger than figure-8 coil TMS (in most meta-analyses) for depression. It is a huge deal.

The men who received this therapy were less violent. It was a huge study, by the way:

313 participants were randomised, 156 to PAU and 157 to MBT-ASPD.

In Table One, we get a sense of who’s in the sample, and that the randomization succeeded:

The outcomes on the primary endpoint—being less aggressive—were really obvious, without any monkeying about with the axis to make it look better. Those vertical bars? They don’t overlap beyond time point one…a month 3 through the end, the men are less violent and stay that way to two years of follow up:

The re-offending numbers were statistically better a full three years after randomization:

The MBT-ASPD group had a significant reduction in total offences by the third year post-randomisation compared with PAU (95% CI 0·36–0·81; p=0·0024), with no significant differences noted at earlier follow-ups.

There was even the dose-response relationship we’d imagine—men who attended therapy with MBT-ASPD had better outcomes:

There were no differences at baseline but higher attendance was significantly associated with improved OAS-M scores at 12 months compared with PAU, particularly in the highest tertile (Estimate=–110, 95% CI –170 to –50·2; p<0·0001).

We can help violent offenders become less likely to be violent subsequently.

These data are large-scale, robust, and important. We have a new, proven tool in reducing human suffering—the suffering the most violent of us inflict on others. We should get this evidence-based approach to many, many more offenders. We should do it for both them and for the rest of us. The replication will be challenging, and it is also a moral imperative. This is a revolution, assuming it replicates, and if only decision makers notice.

Mentalisation-based treatment for antisocial personality disorder in males convicted of an offence on community probation in England and Wales (Mentalization for Offending Adult Males, MOAM): a multicentre, assessor-blinded, randomised controlled trial, Fonagy, Peter et al., The Lancet Psychiatry, Volume 12, Issue 3, 208 - 219

Would love to see discussion of how willingness was cultivated.