Depersonalization and Its Discontents

Testing a brain-circuit based model of a vexing problem.

Welcome to The Frontier Psychiatrists—it’s a newsletter, and more. Today, we are addressing “depersonalization.”

Individuals suffering from this phenomenon:

…experience a detachment from their own senses and surrounding events, as if they were outside observers.

In the DSM-5, it’s “depersonalization/derealization disorder.” It is also a common human experience that can wax and wane without causing impairment. It can, at its worst, be dreadful. Not all problems need to be “a diagnosis” to be worth understanding and addressing. Join me for a dive into the history and the brain circuitry of depersonalization. The term was coined in the late 1890s:

The word ‘depersonalization’ was first introduced by the psychologist Ludovic Dugas (1894). Mayer-Gross (1935) identified two forms of the condition according to whether the feelings of unreality and strangeness referred to self or surroundings, and used the term derealization for the latter. Shorvon (1946) was the first to propose that chronic depersonalization constituted a psychiatric illness in its own right.1

One of the midcentury modern descriptions was penned by Edith Jacobson, M.D., in the Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association in 1959. It struck me. She noted a group of female prisoners in Nazi Germany, who were left to wonder “how this could have happened to them,” and subsequently developed symptoms such as:

“the person will complain that his body or rather certain parts of his body do not feel like his own, as belonging to him.”…This experience may go along with subjective sensations of numbness and of change of size and volume of the estranged body parts. The person may try to touch and feel them in order to convince himself that they are really "his."2

In the less elegant language of 2011, Sierra and David describe it thusly:

Depersonalization is characterised by a profound disruption of self-awareness mainly characterised by feelings of disembodiment and subjective emotional numbing.3

This experience is strange; if you’ve been walking through life feeling the opposite, that your body was yours and full of sensation. Any disorder has not only the subjective experience of “something off,” paired with a separate subjective degree of distress for the person. These two phenomena are separate but crucial to our understanding of the suffering experienced by the individuals in question.

Long-time readers will recall my prior writing about Cotard Delusion, a profound and brutally pervasive disorder of depersonalization that, at least in my narrative, didn’t include the sense of distress around it one might expect:

“I’ve been dead for some time” the gentleman said, reclining in his hospital bed, curiously casual.

There wasn’t a lot of affect in his tone. That’s the sort of thing you say if you’re learning how to do a mental status exam. The patient’s mood was whatever they said it was, but you put that in quotes. This person said “good”. So in the medical note that I was learning to write, I would write mood: “good.” Affect is how the person looks like they feel, it’s an observation. It’s supposed to be objective.

A disorder-ified version of depersonalization is depersonalization disorder (DP), and it’s between rare and uncommon, according to a 2023 review:

The prevalence rates ranged from 0% to 1.9% amongst the general population, 5–20% in outpatients and 17.5–41.9% in inpatients. In studies of patients with specific disorders, prevalence rates varied: 1.8–5.9% (substance abuse), 3.3–20.2% (anxiety), 3.7–20.4% (other dissociative disorders), 16.3% (schizophrenia), 17% (borderline personality disorder), ~50% (depression). The highest rates were found in people who experienced interpersonal abuse (25–53.8%). 4

I’ll recuse myself from making any au courant jokes and continue with our scientific and educational content. Such jurisprudentially-themed humor would be beneath this author.

All in, how common is this depersonalization/derealization disorder?:

The prevalence rate of DDD is around 1% in the general population, consistent with previous findings. DDD is more prevalent amongst adolescents and young adults as well as in patients with mental disorders.

It is worth noting that, in a study of German youth5, this experience is more prevalent among teens.

And it’s statistically more common in girls, which may or may not have anything to do with the fact that girls are wildly more likely to be victims of child sexual abuse:

The other major contributor is cannabis use, which predisposes individuals, particularly youth, to have persistent and pervasive depersonalization in a dose-dependent manner:

In summary, depersonalization is rare, generally, but more common in:

kids

cannabis users

psychiatric patients, particularly those in a hospital

and most prominently, victims of abuse.

What can we do about depersonalization, other than preventing it in the first place?

In a just world, we would be focusing on the prevention of the abuse of children, and that would do away with a substantial portion, along with reducing cannabis use in youth, of associated conditions that may be fuel for the fire.

As I’ve previously written, child sexual abuse, especially of girls, is horrifyingly common:

In the United States, the National Center for Victims of Crimes, as reported in Finkelhor et al. (2009), states that one in 5 girls and one in 20 boys are victims of CSA (Crimes, 2012).

But this is not the world we live in—we will spend endless time ignoring the causes of problems, and pouring gas on fires. Public health is so last year! Thus, for those of us working as healers, we are left with “what to do” when people have been harmed and are suffering.

Can We Think About TMS as a Treatment?

Did you guess I was going to mention Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS)? I’m going to mention TMS. Come on, people. This is Owen Muir, M.D., DFAACAP, writing. It’s not that exciting.

Long-time readers will already have guessed I’m likely to start by referencing data on brain circuits, because that is how I believe TMS to work—by modulating up or down neural activity in brain circuits. One group of authors identified variance in 3 brain networks in those suffering from DPD versus healthy controls:

We identified distinct brain networks corresponding to the Frontoparietal Network (FPN), the Sensorimotor Network (SMN), and the Default Mode Network (DMN) in DPD using group Independent Component Analysis (ICA).6

This has some face validity, in that we’d expect people’s sensory motor network to be “off” if they had symptoms of their sensory experience of their own body being awry.

Other authors have noted structural changes, not just functional changes, in individuals with DDD:

Structural changes, including alterations in cortical thickness and white matter connectivity, provide insights into the disorder’s diverse symptomatology.7

As far back as 2014, clinical scientists were testing this brain circuit hypothesis by using TMS as a tool to treat symptoms of depersonalization transiently (in this small study, they used one session, which causes no durable changes, targeted to two different brain regions):

Patients with medication-resistant DSM-IV DPD (N = 17) and controls (N = 20) were randomized to receive one session of right-sided rTMS to VLPFC or temporo-parietal junction (TPJ). 1Hz rTMS was guided using neuronavigation and delivered for 15 min.8

And it did a little something:

Patients who had either VLPFC or TPJ rTMS showed a similar significant reduction in symptoms.

As of 2021, enough studies have been done to warrant a systematic review, 38 in total, of which 8 met the inclusion criteria in the review, and saving you the details, the stimulation of the temporo-parietal junction (TPJ for short, or “the side of the head,” in common parlance) was “promising,” but studied in enough various modalities that made it hard to synthesize visually.

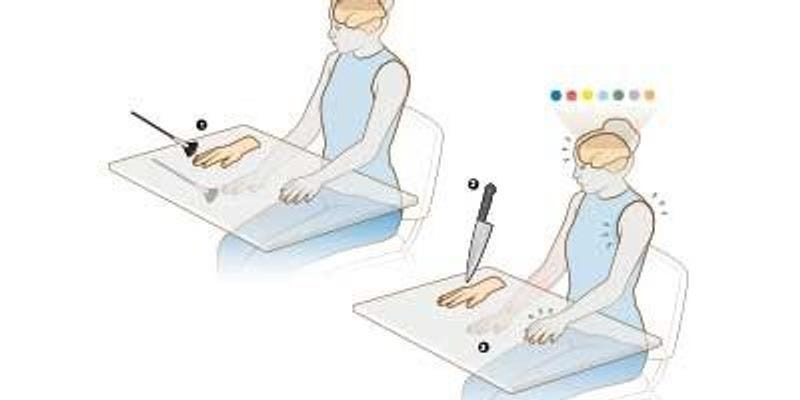

One of my favorite experimental paradigms—for its Radiohead-esque, OK Computer-era Uncanniness— used to explore DPD involves a rubber hand and a mirror, with a knife that stabs the rubber hand to see if the human reacts as if it were their real hand.

In this task, TMS to TPJ was also significant:

The results of the study showed that TMS over the rTPJ decreases the incorporation of the rubber hand into the mental representation of one’s own body (t = 4.67; p < 0.05; two-tailed). On the contrary, authors found an increment incorporation of a neutral object (t = 2.55, p < 0.05, two-tailed).

That other target—the Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex—was evaluated in the single stimulation paper above, and has also been stimulated repeatedly:

Seven patients with medication-resistant DSM-IV DPD received up to 20 sessions of right-sided rTMS to the VLPFC for 10 weeks. Stimulation was guided using neuronavigation software based on participants’ individual structural MRIs, and delivered at 110% of resting motor threshold. A session consisted of 1 Hz repetitive TMS for 15 min.

This open-label case series trial was successful:

20 sessions of rTMS treatment to right VLPFC significantly reduced scores on the CDS by on average 44% (range 2–83.5%). Two patients could be classified as “full responders”, four as “partial” and one a non-responder. Response usually occurred within the first 6 sessions. There were no significant adverse events. A randomized controlled clinical trial of VLPFC rTMS for DPD is warranted.

No one has gotten around to the Randomized Controlled Trial yet, which makes sense given the difficulty of recruiting for an RCT in a relatively rare condition.

Is it about time to get the clinical trial show on the road? Yes. Yes, it is.

I have a day job—when I’m not writing this newsletter— as the Chief Medical Officer of a company called Radial.

If you (or a loved one) are looking for relief from Depression, OCD, Anxiety, PTSD, Bipolar Disorder, or even a compassionate assessment of depersonalization/derealization disorder, feel free to explore care with Radial.

Radial offers the most advanced mental health care.

Radial has physical locations in Midtown Manhattan, Brooklyn, NY; Myrtle Beach, SC; La Jolla, CA; and more, with additional locations coming soon. We currently provide telehealth services in 20 states and are also screening participants for research trials globally.

Mary L Phillips, Nicholas Medford, Carl Senior, Edward T Bullmore, John Suckling, Michael J Brammer, Chris Andrew, Mauricio Sierra, Stephen C.R Williams, Anthony S David, Depersonalization disorder: thinking without feeling, Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, Volume 108, Issue 3, 2001, Pages 145-160, ISSN 0925-4927, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-4927(01)00119-6.

Jacobson, E. (1959). Depersonalization. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 7(4), 581-610.

Sierra, M., & David, A. S. (2011). Depersonalization: a selective impairment of self-awareness. Consciousness and cognition, 20(1), 99-108.

Yang, J., Millman, L. M., David, A. S., & Hunter, E. C. (2023). The prevalence of depersonalization-derealization disorder: a systematic review. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 24(1), 8-41.

Michal, M., Duven, E., Giralt, S., Dreier, M., Müller, K. W., Adler, J., ... & Wölfling, K. (2015). Prevalence and correlates of depersonalization in students aged 12–18 years in Germany. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(6), 995-1003.

Zheng, S., Zhang, F.X., Shum, H.P.H. et al. Unraveling the brain dynamics of Depersonalization-Derealization Disorder: a dynamic functional network connectivity analysis. BMC Psychiatry 24, 685 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-06096-1

Murphy, R.J. (2024). Functional Brain Alterations Associated with Depersonalization/Derealization Disorder. In: Martin, C.R., Preedy, V.R., Patel, V.B., Rajendram, R. (eds) Handbook of the Biology and Pathology of Mental Disorders. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-32035-4_124-1

Jay, E. L., Sierra, M., Van den Eynde, F., Rothwell, J. C., & David, A. S. (2014). Testing a neurobiological model of depersonalization disorder using repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Brain stimulation, 7(2), 252-259.

This a great review !

Most patients with this condition when it is impairing have been on a lot of medications! I find medications really don’t help. A couple of questions- have you had any luck targeting these areas with the H7 without navigation? Or any work at Acacia being done in this area?

Owen, your writing is forever amazing me. Some physicians ignore steroid-induced psychosis. But the DDD is just the beginning!! I look forward to the day when prednisone, Medrol, and Decadron have black box warnings regarding steroid-induced psychosis. Knowing that this is very real might just keep someone out of jail, or prevent an inpatient psychiatric hospitalization.