One of the very exciting things about working on the sharpest part of the bleeding edge of neuromodulation is how fast and furious new data is coming about, and since these methods are safe, able to change practice rapidly.

Today, thanks to my friend Arjun Nanda, M.D., host of The Mental Health Forecast podcast on which I have appeared, along with

in yet another episode…I learned about the following hopeful review.Efficacy of transcranial magnetic stimulation in anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and meta-analysis

This newsletter is becoming the Meta-analysis Star-Ledger,1 but I’ll take it.

In this paper, the authors evaluate the role of TMS treatment in Anorexia Nervosa. I haven't spent a heck of a lot of time on eating disorders (EDOs) on these digital pages, mostly cause I didn’t have a lot to say that was new or useful. The treatment for restrictive EDOs has traditionally been…food. This is a tough sell for people with such disorders. It’s briefly worth noting that EDOs are the most high lethality conditions in the field of psychiatry. That is right, it’s not depression—not by a long shot. It’s eating disorders that are most likely to lead to death. For example:

The crude mortality rate was 5.1%. The standardized mortality ratios for death (9.6) and suicide (58.1) were significantly elevated (p < .001).2

Somewhat surprisingly, being hospitalized for a mood disorder in women with co-occurring mood disorders is protective…

Standardized mortality ratios were elevated for all causes of mortality (11.6; 95% confidence interval, 5.5-21.3) and suicide(56.9; 95% confidence interval, 15.3-145.7) in anorexia nervosa but not for death (1.3; 95% confidence interval, 0.0-7.2) in bulimia nervosa. Predictors of mortality in anorexia nervosa included severity of alcohol use disorder during follow-up (P<.001). Hospitalization for an affective disorder before baseline assessment seemed to protect women from a fatal outcome (P<.001).3

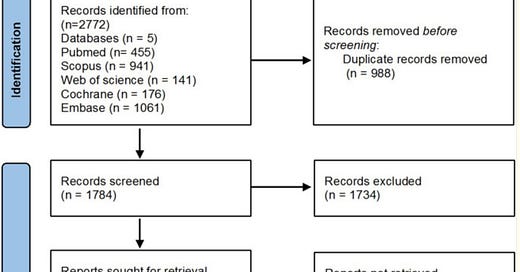

Now, given the data about how fatal these problems are, let’s move on to the news. With transcranial magnetic stimulation, we might have a new effective treatment toolkit! In what is likely a thankless task, the authors screened 2772 publications for inclusion. They had enough data to include nine papers in the meta-analysis.

A primer on how to interpret Meta-Analysis data is here. And a more extensive dive is available in chapter one of my book, Inessential Pharmacology. (amazon affiliate link).

This is—to be clear—only data on Anorexia Nervosa, not other eating disorders.

Who was in the study:

The present meta-analysis consists of 129 participants with a mean age of 32.41 ± 7.27 years and a mean disease duration of 14.57 ± 6.66 years.

Where did they stimulate in the brain? A range of targets!