Checking the Locks: Avoiding the Horrors of Involuntary Psychiatry

Given New York Times coverage of Acadia Healthcare...some data to drive decisions.

Quick Book Plug: Inessential Pharmacology. 4.8 ⭐️ on Amazon….now, the article:

The article published over the weekend in The NY Times was pretty devastating:

Acadia has lured patients into its facilities and held them against their will, even when detaining them was not medically necessary.

I work at Acacia Clinics, which is not the same as Acadia Healthcare. Thanks for asking. I’m glad I can clarify for readers. I have worked in many hospitals, all of which were under the opposite pressure as that described in the Times article:

Acadia, which charges $2,200 a day for some patients, at times deploys an array of strategies to persuade insurers to cover longer stays, employees said. Acadia has exaggerated patients’ symptoms….

Unless the patients or their families hire lawyers, Acadia often holds them until their insurance runs out.

“We were keeping people who didn’t need to be there,” said Lexie Reid, a psychiatric nurse who worked at an Acadia facility in Florida from 2021 to 2022.

Acadia was accused, with 50-odd interviewees, of literal kidnapping—holding people behind a locked door on the pretense of being “psychiatric patients” for profit. To be unbelievably clear—kidnapping is a crime. It is a felony. With everything in my being, I hope that the described circumstances in the Times will be investigated and that, if substantiated, every person involved will face criminal charges and prosecution, and legal standards will be set, yet again, that preying on the vulnerable is unacceptable.

I also have every reason to doubt this will be the case. This article is not, however, about kidnapping. It’s about the data that make such kidnapping make no sense in any other setting. Distorted payment models make psychiatric inpatient care across the land a disaster for patients and helpers alike. It is our poor insight into the utility of involuntary care, however, that is the root of the problem—and what made Acadia’s allegedly criminal profiteering so plausibly for so long.

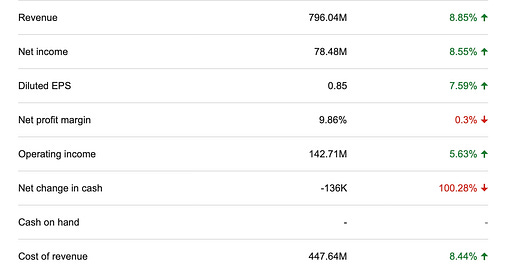

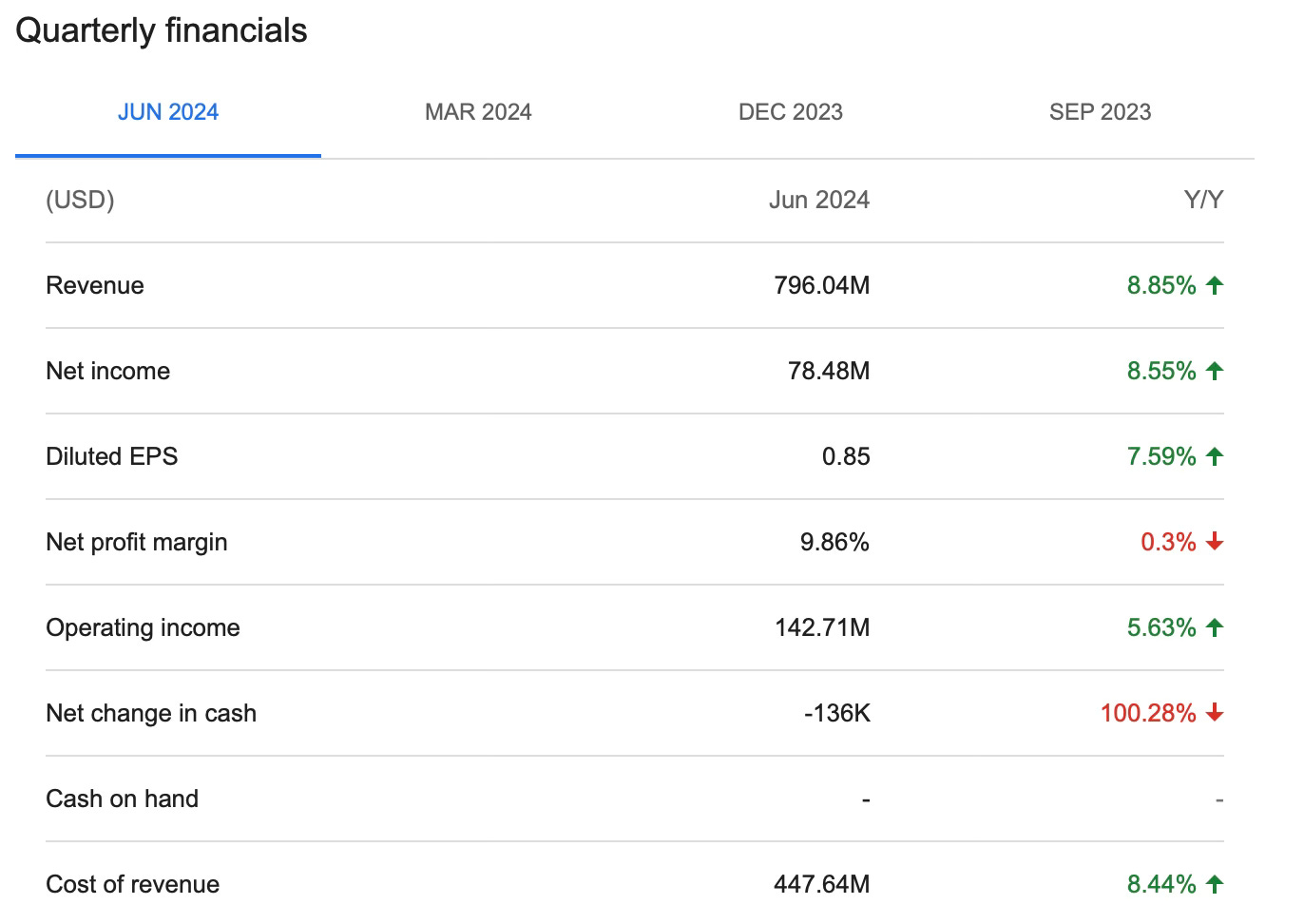

Acadia Healthcare is a publicly-traded company. Here are some of their most recent financials:

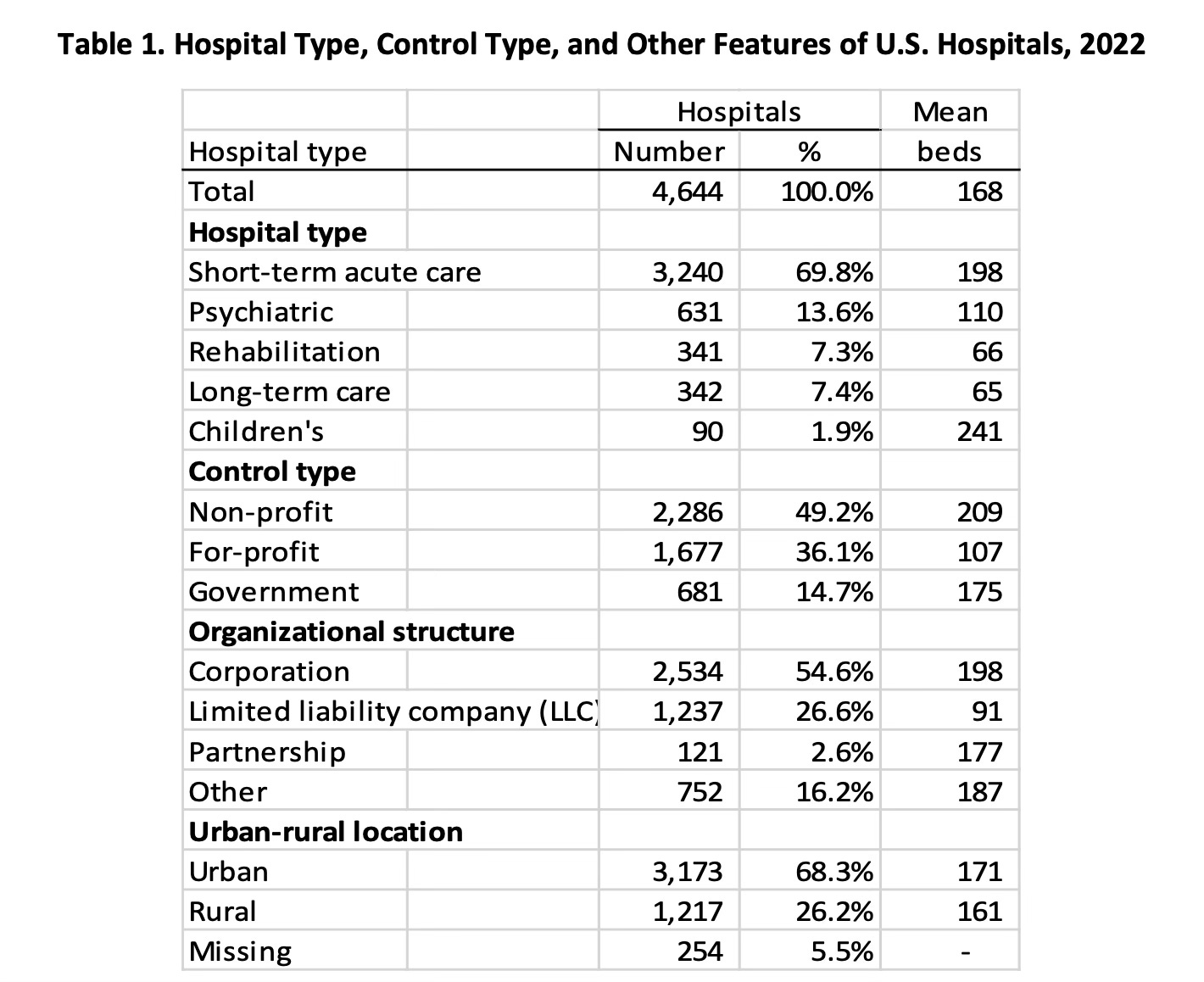

It is a profitable for-profit company. At least, it was profitable prior to the litigation that will now ensue. Most inpatient psychiatric care is provided in non-profit hospitals, by a slim margin, per HHS in 2022:

The “government” hospitals includes the State Hospital system, which is where patients too sick for shorter term psychiatric hospitalization go to be able to undertake the increasingly rare longer stays that are sometimes felt to be necessary. From a financial perspective, those state hospitals are a money sinkhole that protects the profits of the for-profit enterprises. They are a subsidy for Acadia Healthcare and it’s ilk. If a patient is going to stay for too long in an acute hospital, they get transferred, along with their expenses, to a government funded hospital.

Only psychiatric hospitals allow for involuntary treatment—and for the most part, this is heavily dependent on the laws of the state in which they operate. I live and work in the relatively draconian state of New York, where we allow for up to a maximum of 15 days (before seeing a judge) on an emergency admission, up to 60 days on a “two physician certification,” which is another type of involuntary hospitalization, and that is among the more restrictive legal standards in the country. New York has subways citizens can be pushed in front of…and that means, we tend towards a limited amount of freedom for the mentally ill. Other states—like New Hampshire— have no locks on the doors of any unit in the entire state (other than it’s one State Hospital). Yes, there are unlocked (and thus voluntary) psychiatric inpatient units. There should be vastly more of these, according to me—a doctor who’s been a voluntary inpatient. I believe this to be a good idea because we already have the data to answer this question: “are locked or unlocked units safer?” It's worth remembering that suicide prevention is complicated. What does the data have to say about involuntary hospitalization, which practically speaking, means doors with locks on them?

As far back as 1960, one hospital undertook a mirror image study design—first locking, and then unlocking it’s doors:

One paper focussed on aggression with regard to locked doors. Folkard (1960) monitored the incidents of aggressive behaviour for 20 consecutive weeks: the first 10 weeks the door was kept locked, and the last 10 weeks the door was opened for the first time.

During the locked phase there were 249 aggressive occurrences and during the unlocked phase only 193. This reduction in aggressive incidents coincided with the decrease in actions taken by the staff (from 57 during the locked phase to 46 during the unlocked phase). Staff actions included sedation, E.C.T. or putting the patient to bed. Folkard (1960) noted that staffing levels might also influence aggression.

It makes “common sense” to think that the locks on hospital doors do…something. However, we have very little evidence to suggest it’s useful. We have ample evidence to suggest unlocked doors are beneficial, even if it’s very dated:

The literature on locked doors in inpatient psychiatric wards was inconclusive regarding the effects of locked doors. While there were ample empirical (Scott 1956, Wisebord et al. 1958, Wake 1961) and non-empirical literature (Koltes 1956, Ryan 1956, Snow 1958) from the 1950s and 1960s regarding the open door, there was very little on locked doors.

One would imagine locked doors prevent people from running away. In the UK they refer to this as “absconding” and in the US we tend towards the term “elopement.” However, we don’t have that kind of evidence. Psychiaric patients are resourceful—they can and do run away from locked units:

in a large retrospective study of absconding at All Saints Hospital in Birmingham, just under half of all absconds [ed: that is british for running away] occurred from locked wards (Antebi 1967). Somewhat similarly, Coleman (1966) reports 20% of absconds, and Richmond et al. (1991) 21%, at Veterans Hospitals in the USA were from locked wards.1

The acute psychiatric inpatient service in Christchurch, New Zealand, changed from two locked and two unlocked wards to four open wards. A paper was published on the outcomes:

Rates of unauthorised absences increased by 58% after the change in ward configuration (P= 0.005), but seclusion hours dropped by 53% (P = 0.001).2

Other studies have found no difference in the UK:

one-way analysis of variance between the permanently locked wards (n= 41), partially open wards (n= 49) and permanently open wards (n= 46) did not show significant differences in absconding rates between the three ward types [F(2,133) = 2.8, P= 0.067].3

It’s far from a settled matter to assume that locks prevent patients running away, empirically. It’s similarly seductive to assume locked doors do something useful for safety…except, they don’t: