The Frontier Psychiatrists is a daily health-themed newsletter. Today, I’m following a thread unearthed by my prior articles on akathisia (an adverse effect of Abilify and other antipsychotic drugs). A reader pointed out that the phenomenon is eerily similar to one described in meditation circles as “samadhi pain” (according to Shinzen Young). This led to me ask the question that is the topic of today’s writing—is mediation a dopamine circuit modulator, and thus producing the same adverse effects in some individuals as antipsychotic medications?

Here is my description of akathisia:

Imagine going to the most dreadful movie you’ve ever experienced—if Michael Bay re-made an Inconvenient Truth—and being forced, with a gun to your head, to not move an inch. Imagine being forced to listen to some tech bro mansplain Bitcoin, and having to smile, motionless, the whole time…if you were secretly Satoshi Nakamoto. Now take those feelings, and move them away from the world of words, into your legs. Have to move them. Have. to. move. them.

The horrible part of this inability to remain motionless is that the movement doesn’t scratch the itch very well. People who experience akathisia will pace back and forth, but it never really feels better.

A reader summed it up as “restless leg syndrome for the soul” and, not knowing Shizen and I are acquainted, sent me his description from an article entitled:

“The Icky-Sticky Creepy-Crawly It-Doesn't- Really-Hurt-But-I-Can't-Stand-It Feeling”

meditators sometimes go through periods when the more they relax, the worse they feel! Specifically, there is a distinct kind of yucky body discomfort which occasionally arises in meditation. There is no single expression in the English language to denote this quality of sensation although we ought to have a word for it since it is such a common phenomenon. I once heard a famous Burmese teacher refer to it as "samadhi pain" because unlike other discomforts which immediately improve when you go deeper into samadhi(relaxation, concentration), this discomfort can get temporarily worse. The best I can do is try to characterize it in a few sentences. If you have ever experienced it, you will immediately recognize what I am trying to describe. For lack of a better term, I sometimes refer to this phenomenon as "relaxation pain."

The only error in Shinzen’s description is, perhaps, the “no single expression” contention! It sounds a heck of a lot like Akathisia! Shinzen continues:

The body may even move, shake or twitch as though it were in extreme agony, but there is little actual pain. It seems unbearable, yet it doesn't actually hurt. The worst part is that the more you relax, the "yuckier" you feel. When this phenomenon arises, it seems that the last thing you would want to do is to keep still for even a moment.

Sure sounds like Akathisia! Dr. Sachdev argues in a similar vein in this 1995 paper:

Even though the term has come to be used synonymously with drug-induced akathisia, its origin was in the pre-neuroleptic era, and it is still often used to describe syndromes not related to medication.1

Akathisia, we will recall was first described in 1903, by Hastovec.2

We have two similar-sounding pairings of internal experience and hard-to-describe sensations. For us to accept the hypothesis that they share similar pathophysiology, we’d need evidence that mediation had some impact on the same neural circuits that dopamine-blocking drugs do? Like, for example, this article, entitled:

Increased dopamine tone during meditation-induced change of consciousness

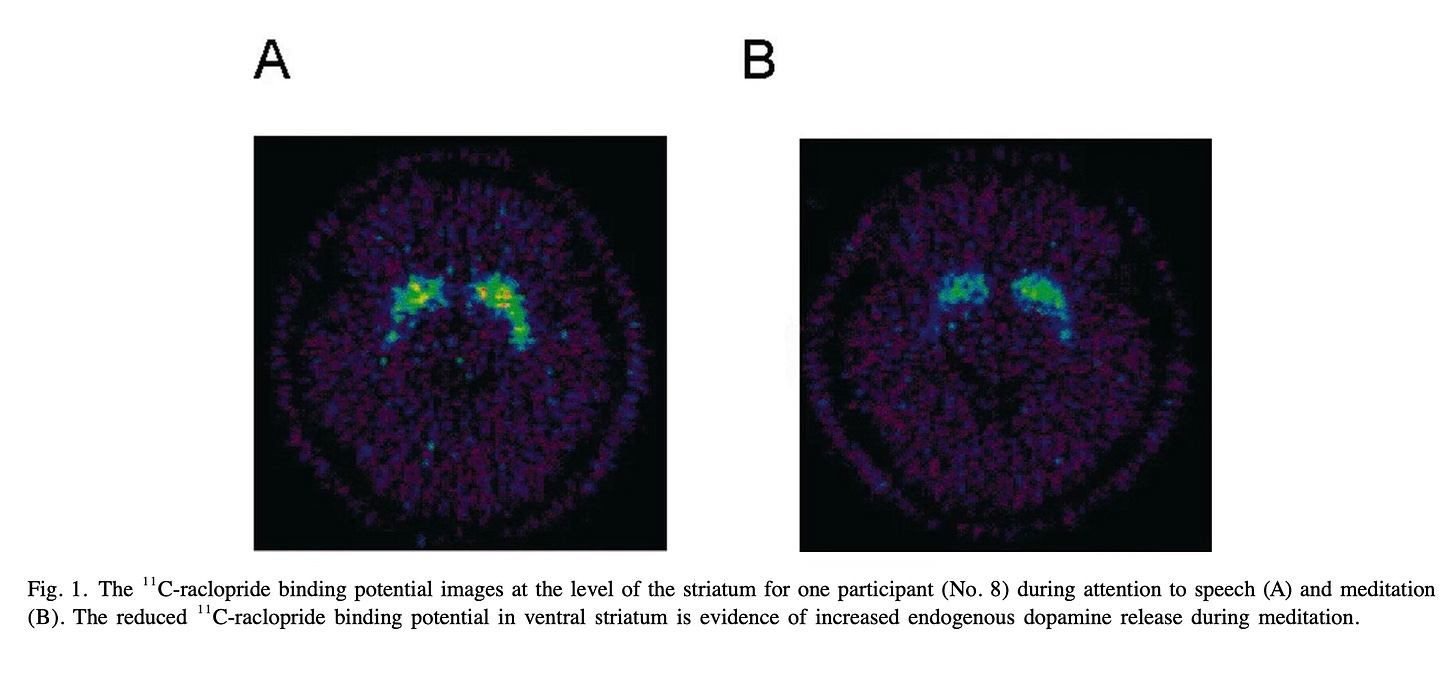

In which they popped meditators into a PET scanner:

Using 11 C-raclopride PET we demonstrated increased endogenous dopamine release in the ventral striatum during Yoga Nidra meditation.

PET of course stands for positron emission tomography, and I addressed some of the complexities around computing tomography with different radio frequencies in prior articles like this one. The methodology is actually not too complicated, even if the physics of how the image is captured is. In these PET scans, Scientists use a radio-labeled tracer that is selective for specific neurotransmitters, not just the non-specific changes in BOLD signal from increased cellular metabolism as seen in my beloved fMRI scans.3

The tracer competes with endogenous dopamine for access to dopamine D2 receptors.

When more dopamine is released, you see less tracer bound. This is what they saw comparing within-individuals. They did two scans per person, one just lying there, and one meditating:

[11] C-raclopride binding in the ventral striatum decreased by 7.9%. During meditation, this corresponds to a 65% increase in endogenous dopamine release.4

Meditation, in real-time, releases more dopamine in the ventral striatum, which ardent readers will recall is the home of the nucleus accumbens (as featured in both the akathisia article and the article on the topic of compulsive behavior related to aripiprazole).

Subsequent authors used SPECT scans to evaluate changes in dopamine on the time scale of pre-post meditation retreat:

We observed significant decreases in dopamine transporter binding in the basal ganglia and significant decreases in serotonin transporter binding in the midbrain after the retreat program.5

The spatial resolution of the SPECT devices I have mocked in prior comedic performances. Suffice it to say, midbrain and basal ganglia are about as good as we are getting with a SPECT scan. Other authors have noted that, grossly, there is a variety of data describing neurotransmission level variation in meditation:

dopamine and melatonin are found to increase, serotonin activity is modulated, and cortisol as well as norepinephrine have been proven to decrease. These findings are reflected in functional and structural changes documented by imaging techniques such as fMRI or EEG.6

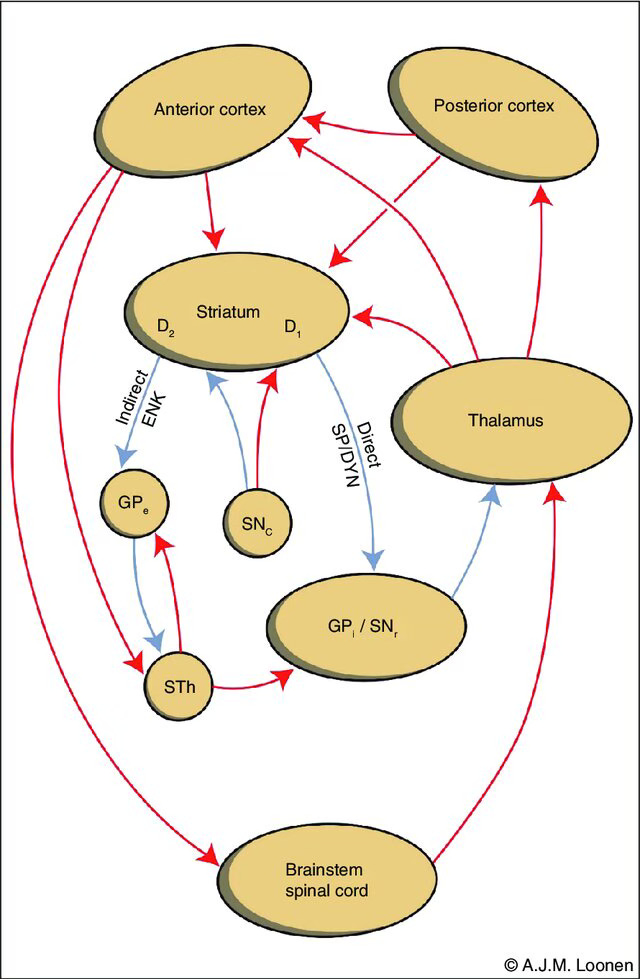

If movement disorders research has taught me anything, it’s that none of this is simple, when we drill down into the actual circuits involved.

We end up getting “an inhibition of an inhibition of an inhibition” explanations which—while true—are hard for the human brain to grok. For example, I’m sure the following is endlessly intuitive:

Those graphics are intended to illustrate one point, much like Herr Zuckerberg chose to memorialize our inability to describe human relationships circa before he destroyed our ability to have them in the real world: It’s complicated.

From Shinzen’s description, if we accept that he is describing an experience that will have a plausible neurobiology akin to akathisia, we need to back solve to plausibility for this to be a good article.