Psilocybin In Pandemic Traumatized Healthcare Workers

How I read a theoretically exciting paper.

People love—and I mean LOVE—to share research with me. Hi friends! Welcome to The Frontier Psychiatrists Newsletter. Today, I walk my readers through a recent paper. I want everyone to feel like science is less of a mystery. We can all do a little bullsh*t parsing on our own, fancy degrees or not.

Psilocybin Therapy for Clinicians With Symptoms of Depression From Frontline Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic. A Randomized Clinical Trial

First, a brief promo:

Tonight, we kick off the JPM Health conference in SF. There are still a few tickets left, so consider joining us.

Now, let's get into the trial!

COVID-19 was a nightmare for many of us, but for modern healthcare workers, it was Stalingrad, Somme, Fallujah, and Cannae. If my children are reading, those are all battles and worse that were very bad.

The question the Study tried to answer— but failed in definitively demonstrating—is if you took individuals exposed to the trauma of Frontline care amid a pandemic, who are currently suffering depression symptoms, and gave them a touch of psilocybin, versus a placebo control, it would demonstrate that psilocybin was an effective treatment for depression, trauma, and burn out.

It's important to maintain skepticism about very potential potentially exciting treatments, the more hyped, the more skeptical I'm gonna be. There's one metric I noticed looking at this paper published in JAMA Open1:

I always love to look at a method section, so let's take a look at who they enrolled in the study:

Design, Setting, and Participants This double-blind randomized clinical trial enrolled participants from February to December 2022. Participants included physicians, APPs, and nurses who provided frontline care for more than 1 month during the pandemic and had no prepandemic mental health diagnoses but had moderate or severe symptoms of depression at enrollment.

APPs are advanced practice nurses, like nurse practitioners. The hardest part of these inclusion criteria is the “no pre-pandemic mental health diagnoses” — psychiatric problems are common in the population and even more common in healthcare workers, but if you screen enough of them, you can find people where nobody called that problem before exposure to a life-altering trauma.

They used some novel inclusion measures to make sure that people were exposed enough to frontline care-related trauma:

These items included caring for a patient critically ill with COVID-19, working longer hours to provide care to patients with COVID-19, witnessing or responding to a death from COVID-19, or caring for a patient who died without their family present due to pandemic-related precautions

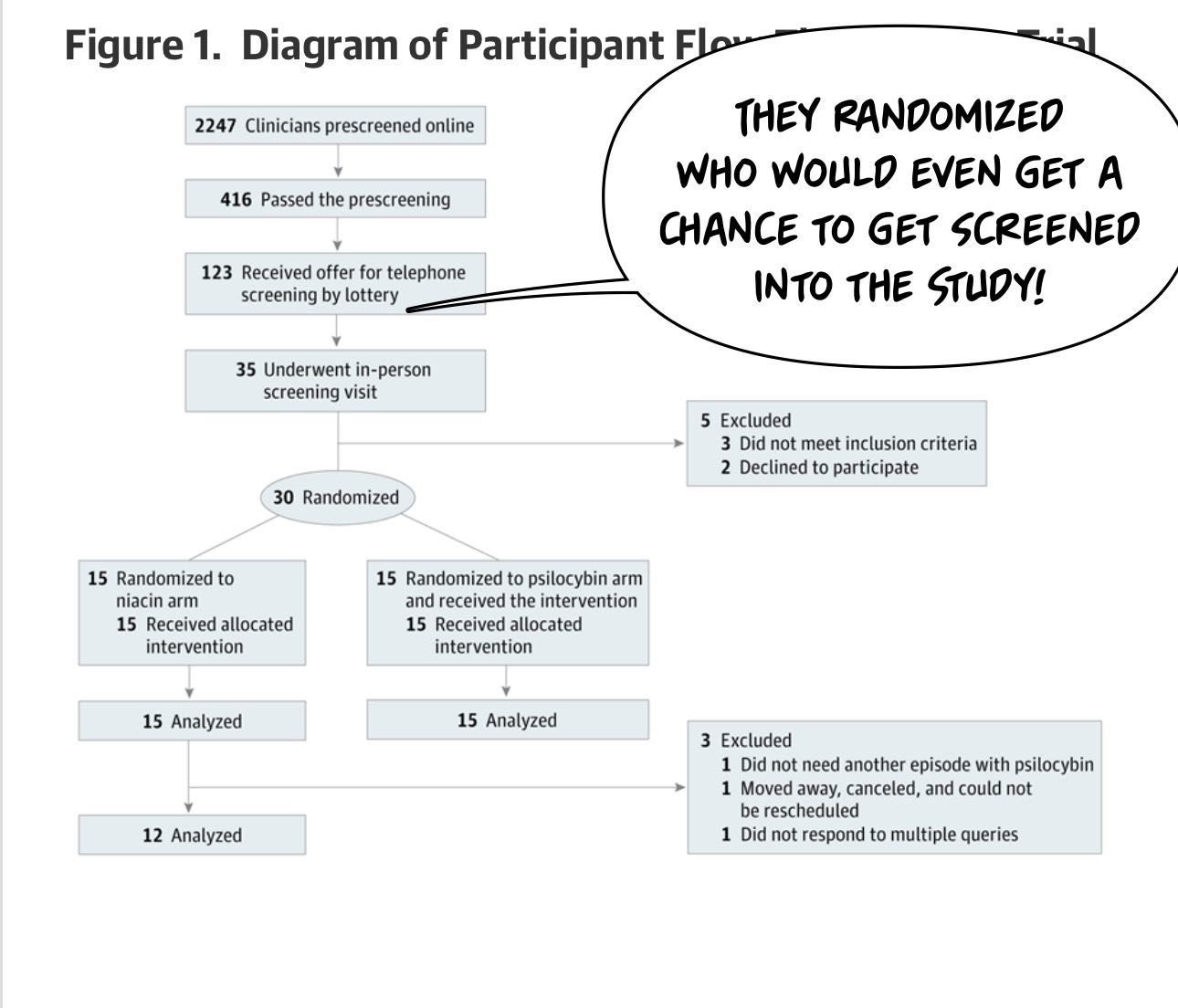

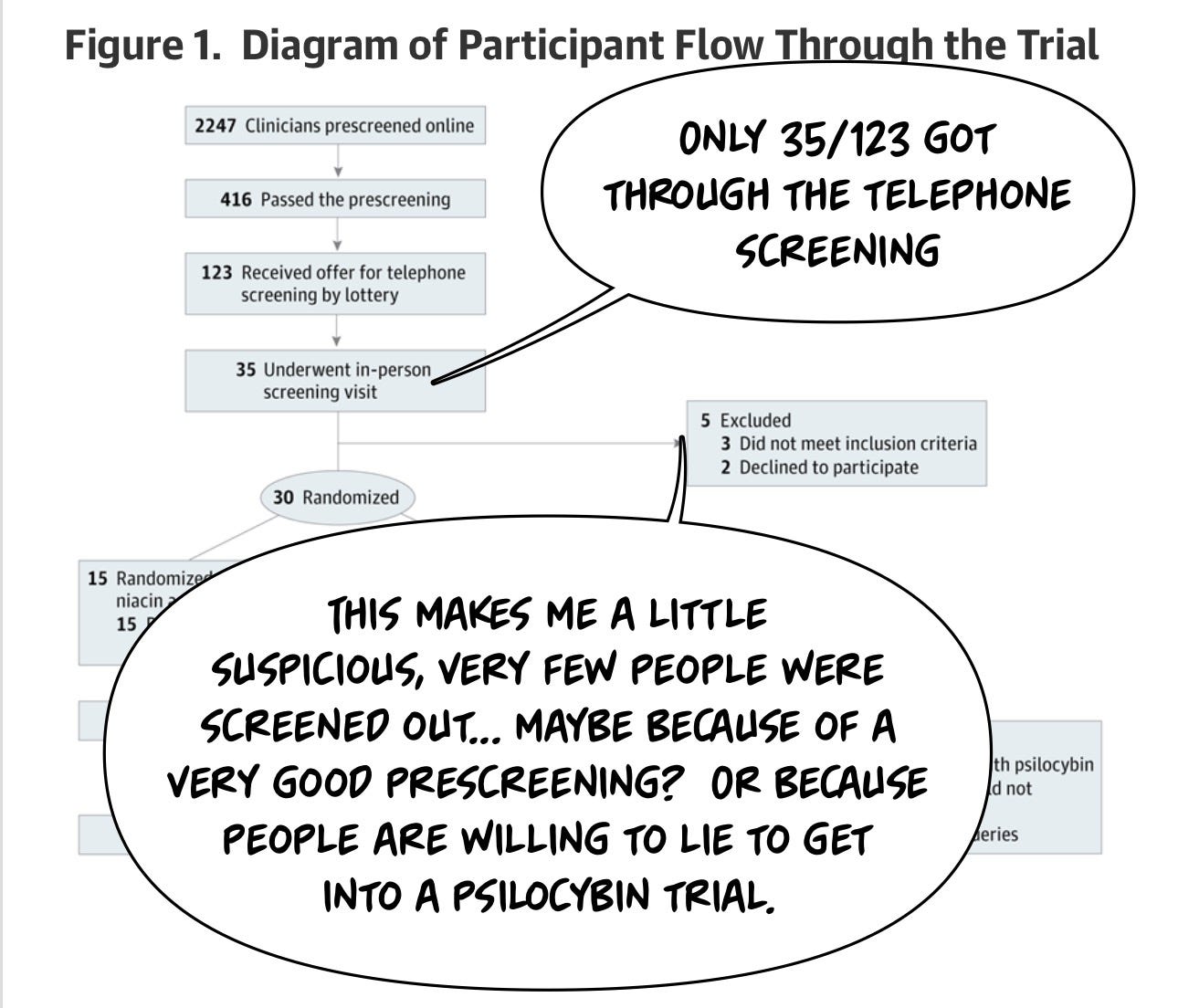

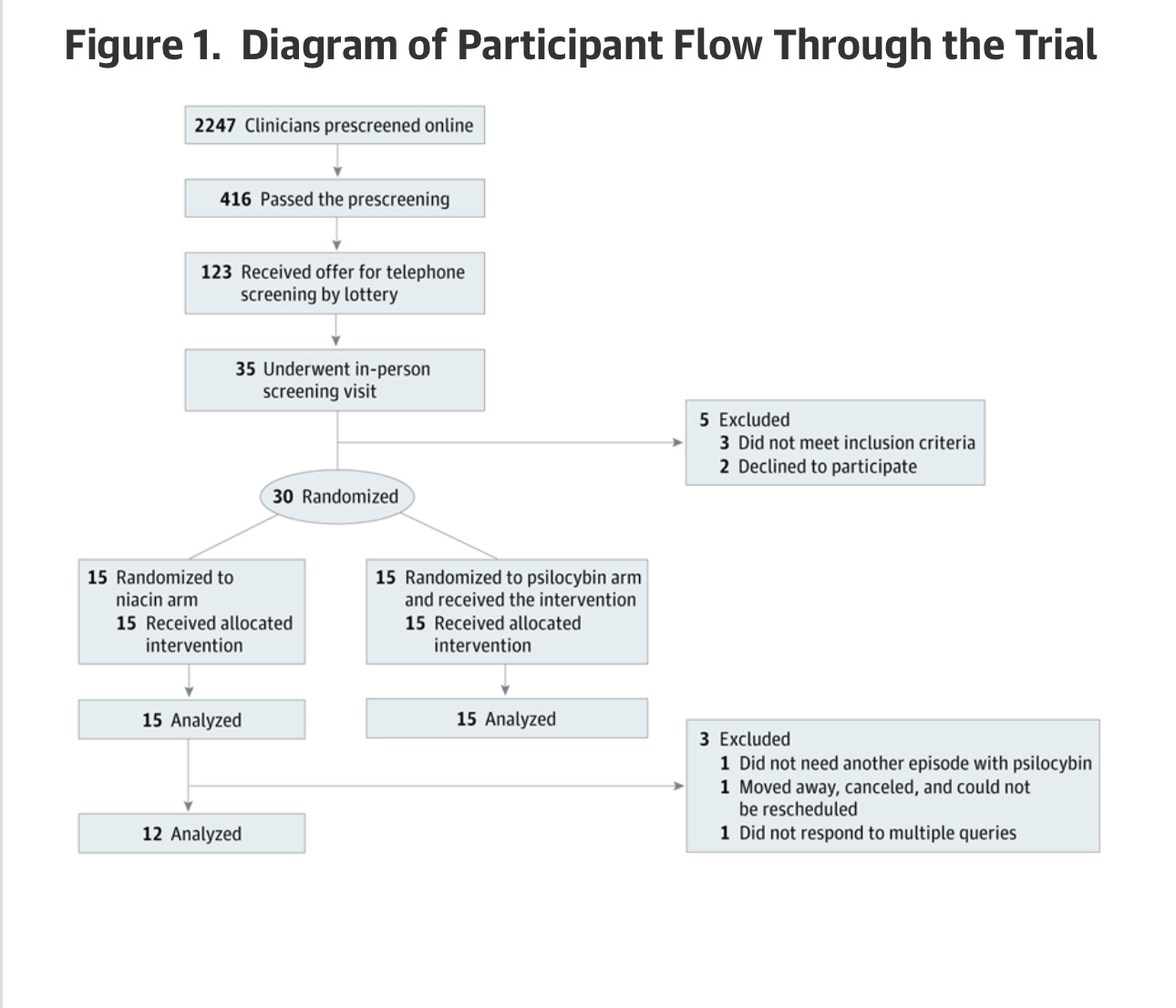

One thing you're probably wondering is, if you're trying to enroll for a clinical trial like this, how many people are gonna show up? Psilocybin is popular in the Zeitgeist, and I imagine there are a lot of traumatized healthcare workers, so can we find a group of people who enroll in our trial? The answer is in the CONSORT diagram, which shows, in a standardized way, how many patients came through the Study. And if you take away anything from this article, it's probably “And if you take away anything from this article, it's probably "Oh my God, a lot of people will want to get into a psilocybin trial!”

2247 people applied online to be screened for the trial. A lottery was used to decide who would receive a phone call inviting them to a screening.

One of the things I wonder about studies like this is how much people are willing to lie. Research participants often want to be included in the research study, and this is a cohort of healthcare professionals who knew they could get a very hyped treatment and contribute to the well-being of their fellow healthcare workers. I think this cohort is slightly less likely to lie about getting into a research study because we all rely on those research studies, but I… don't actually know.

I do know a lot of people wanting to get into the study. Many, many people are suffering after the experience of frontline care during the pandemic. There were thousands at the door.

The participants in this trial had their pre-Covid lack of mental health diagnosis assessed only by self-report. The authors just… believed them. That's a reasonable choice, but there is some possibility of bias. One might imagine that they could've checked. Even this might have introduced additional bias!

In a study, when you decide to check a history, you need to obtain prior records. This means you're including people who are organized enough to have their prior records. Or motivated enough to want to go through the extra steps of providing you with medical records. And how do you prove that someone didn't have a diagnosis? Do you look at every medical record they provide you? And make sure no one snuck in a historical diagnosis? Some questions are best answered quickly and easily because an attempt at a more definitive understanding either isn't worth it or introduces its own bias. Healthcare workers are notoriously bad at accepting care for themselves, so even if you did the most diligent job you can imagine of making sure that nobody has documented the diagnosis before, it still doesn't answer the question meaningfully of whether one was present. The same healthcare worker who would presumably be “lying” to you to get into the fancy study is exactly the same kind of person who would've lied previously about not having a mental health problem in order to have it not impact their job. One might argue that people who keep meticulous medical records are different from people who don't keep meticulous medical records.

My point is that some biases in study design are unavoidable, and I think in this trial, the choice to just ask people and move on was an appropriate one.

One of the benefits of psilocybin, when it comes to running a research trial, is that unlike people dying of cancer, you don't need to lie to a researcher to get access to psilocybin. You can buy it on the street like everybody who's been using it for years. Maybe you can even find it in the forest, but you don't have to be in a clinical trial; only a clinical trial is needed to access the thing. And if you have a choice between asking your cool friend who knows how to get drugs and going through an extensive screening and evaluation process and then being randomized to a 50% chance of getting the drug, I think that's a lot less likely.

I think you for the kind of person who likes to play fast and loose with the rules, you're gonna find a cool friend, or you might even be that cool friend. I don't think you will bother enrolling in a research study. I suspect these research participants were very earnest. Which, again, introduces its own bias. Do we imagine the very earnest individuals who desperately want to be part of research trials so that new science can help their colleagues and themselves are different from the people in the general population who decide they don't want to do that?

I suspect they're different from people who don’t make those choices. This impacts generalizability.

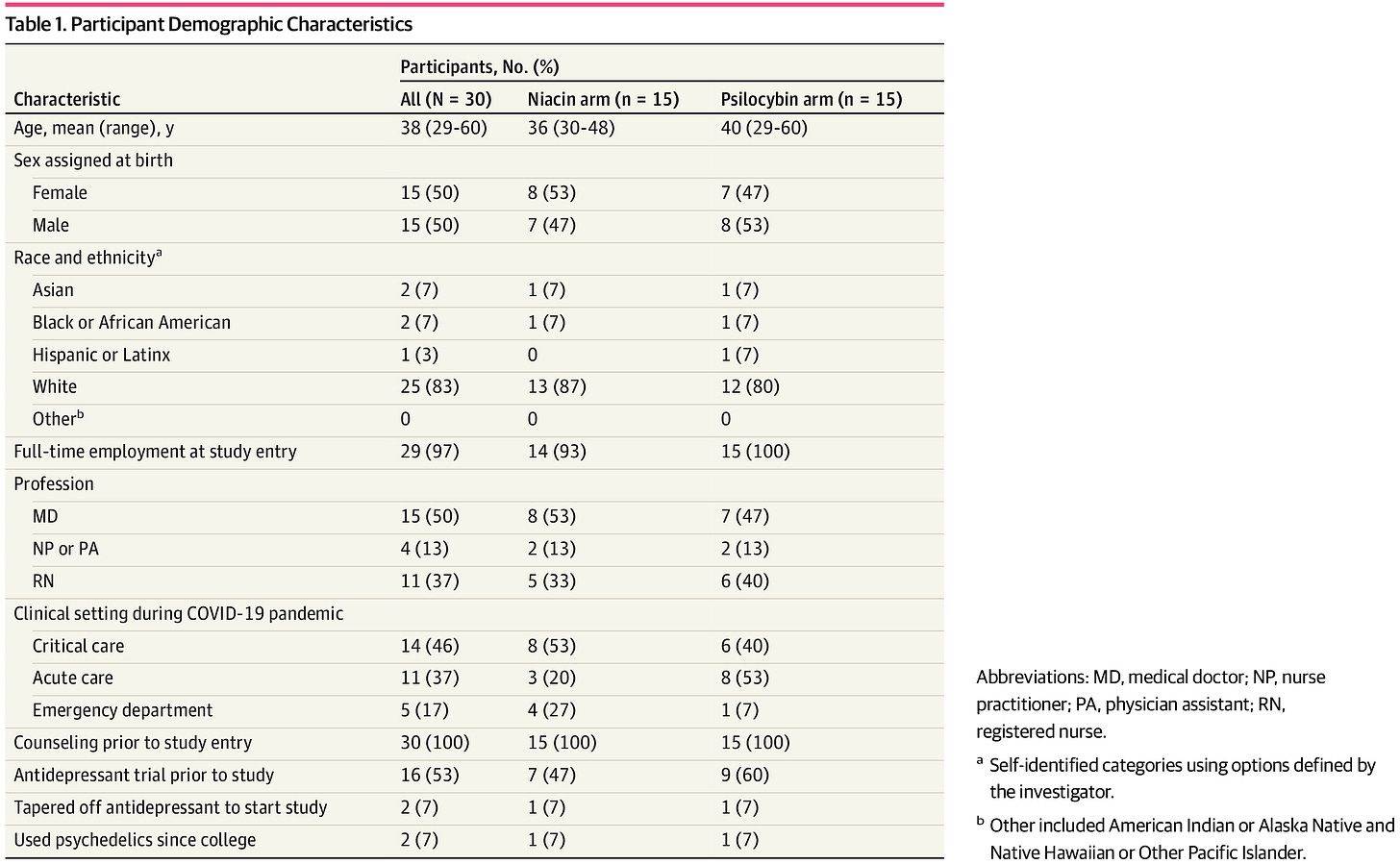

Now, let's see how different they are in table one! Only 30 individuals are randomized for this trial, which I'm presuming I had to do with funding. These psychedelic trials are a massive pain in the *ss to do— it's a DEA Schedule I drug.

It always annoys me when they don't provide data on if the randomization succeeded. They just… don’t say in this paper. There are plenty of white people, as in many psilocybin studies.2

But it does, to my eyeball, look like there are different numbers of emergency medicine settings folks randomized to the Psilocybin Group compared to the Niacin (“placebo”) group. Here is the high level of the study design:

Participants were randomly assigned to either the psilocybin or niacin arm. Data analysis was conducted between December 2023 and May 2024 and was based on the intention-to-treat principle.

And they found two important things:

First, 100% success in guessing (among healthcare professionals) if one was assigned to the niacin or placebo group. Complete, perfect, functional, unblinding. Thus, referring to this as a double-blind trial is odd. It’s as close to factually false regarding a title as possible? Doctors and nurses can guess if they got psychedelic mushrooms, which is a less splashy title.

Second, the study did show that in this entirely unsuccessfully blinded trial, evaluating depressed healthcare professionals, in a completely obvious to all subjects way, people reported more significant improvement in depression symptoms with psilocybin than niacin.

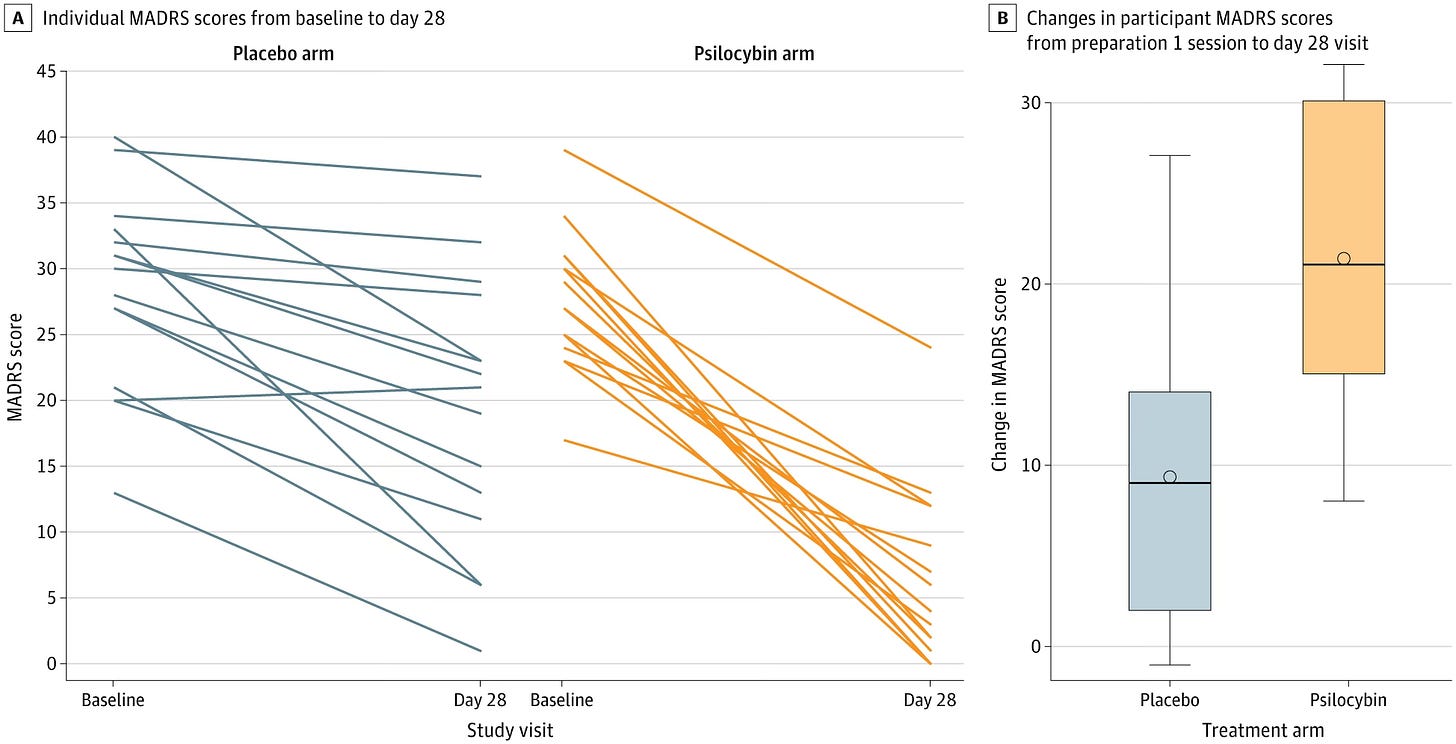

For the primary outcome, the mean (SD) change in MADRS score from preparation 1 session to day 28 was −21.33 (7.84) in the psilocybin arm and −9.33 (7.32) in the niacin arm, with a mean difference in change scores of −12.00 (95% CI, −17.67 to −6.33; P < .001) (Table 2and Figure 2). The decrease in MADRS scores (indicating improvement) in the psilocybin arm was sustained through the month 6 follow-up (mean decrease, −24.00; 95% CI, −26.87 to −21.13) (Figure 3). To put these MADRS score decreases into context, the minimum clinically important difference in change scores is 1.6 to 1.9.3

Notes before we wrap:

This is somewhat unsurprising—of course, in people who can tell for darn sure they got a thing thousands lined up to get access to a study on they felt better.

The fact the burnout scores didn’t reach statistical significance makes me believe it is more on the depression outcome side, not less:

The mean change in SPFI [ed: a burnout measure] scores from preparation 1 session to day 28 showed a numerically larger improvement in symptoms of burnout in the psilocybin compared with the niacin arm (-6.40 [5.00] vs -2.33 [5.97]; P = .05) but was not statistically significant.

It’s not like subjects were reporting everything was so much better. Or maybe working in healthcare is so burnout-inducing that not even 25mg of shrooms can make one trip hard enough to forget prior auth.

Thanks for reading!

I hope to see many of you tonight. I hope we all learned a little about research study design and enrollment!

Back AL, Freeman-Young TK, Morgan L, et al. Psilocybin Therapy for Clinicians With Symptoms of Depression From Frontline Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open.2024;7(12):e2449026. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.49026

Tabaac, B. J., Shinozuka, K., Arenas, A., Beutler, B. D., Cherian, K., Evans, V. D., ... & Muir, O. S. (2024). Psychedelic Therapy: A Primer for Primary Care Clinicians—Psilocybin. American Journal of Therapeutics, 31(2), e121-e132.