What Can SantaCon Teach Us About Factor Analysis?

An absurdist argument for an important statistical concept.

The Frontier Psychiatrist is a daily health-themed newsletter. Thank you for joining us. Today, it's a little bit of math nerd and a little bit of humor.

Santa is a character who does not really exist. Elves? Also fictional. And yet every year, a strange thing happens in my home city of New York. There is a storm of hundreds who get dressed…strangely. Something odd is happening. There is this weird coincidence. There is a day every year when, in late December, walking around surrounded by a sea of Santa Claus-garbed individuals. On that same day, elves spread up all around the city for reasons unclear. There is additionally, among those dressed as either Santa or dressed as an elf, a sudden onset movement disorder that seems to be rapidly progressive. There is, in a large population of young and healthy individuals, prominent ataxia. This is a disorder in which one has lost the ability to maintain balance and coordination of the body's trunk. It's odd to see it! Dozens, hundreds of young Santas and young elves, all of whom, over just one day, are developing a horrific movement disorder. Who knew that neuropsychiatric syndrome could be so common and so rapidly progressive, especially in a cohort who love Christmas so much?

Except that is not what is happening at all. This absurdist description allows me to make a nerdy point about math and science. My readership is not surprised, which is an emerging property of having written almost 600 articles that are nerdy riffs on math and science.

So what is happening, in fact? Either, by chance, hordes of individuals decided to dress up as Santa, or there's an unobserved factor that explains the observed variability.

The unexplained factor is a day called SantaCon, a convention for Santas, on which people get dressed up like Santa and all go out drinking in Manhattan at once. It's not an accident. There is a date set, and people don't get dressed up as Santa and get blasted on the Lower East Side on days other than that particular day— it would be lonely and awkward.

The unobserved factor explains the observed variance. This is what factor analysis is all about. Can we pause an unobserved factor that explains what we see better than looking for statistical relationships between observed factors alone? This assumes that we might be missing something underpinning the observed phenomenon.

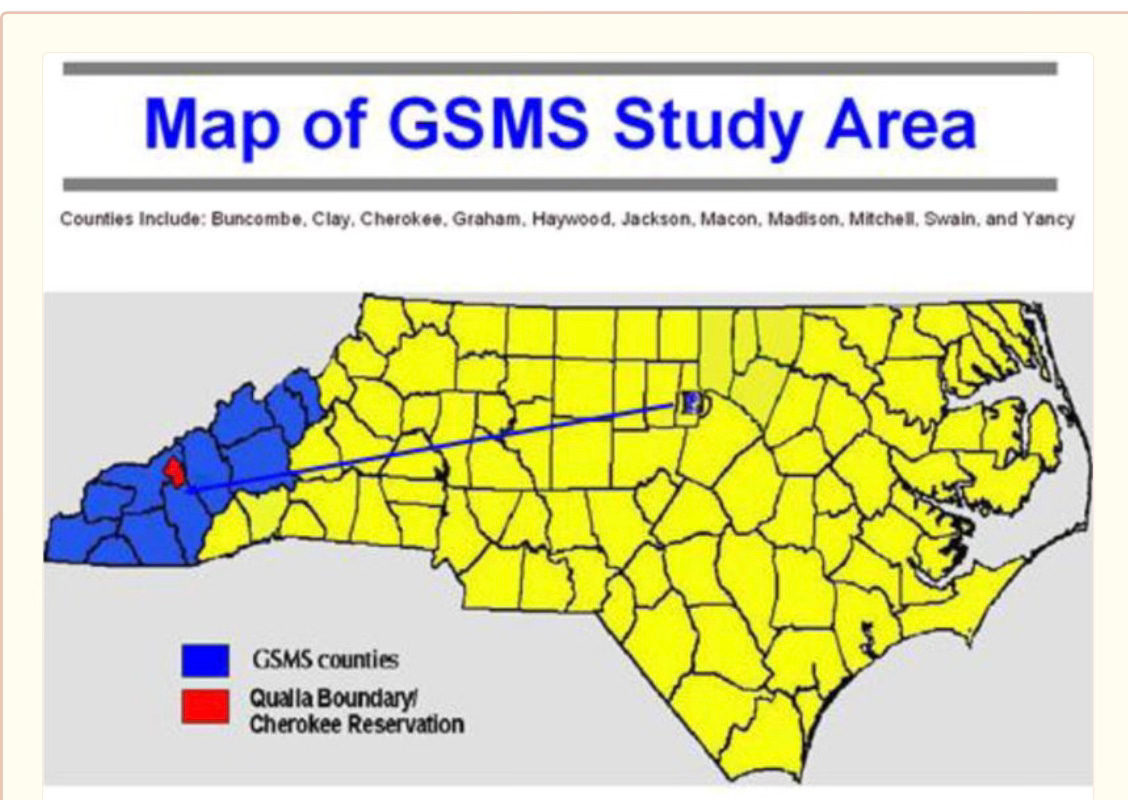

There is a reason. Factor analysis seeks to determine those underlying reasons. Is it likely that there's an underlying reason? How many underlying reasons might explain what we're seeing? We've used this approach in large epidemiological samples; people are not being randomized conditions but were observing a hell of a lot of data. One of the largest longitudinal epidemiology studies of psychopathology over time is called the Great Smoky Mountains Study. It’s a remarkable longitudinal trial:

The Great Smoky Mountains Study (GSMS) is a study of child psychiatric epidemiology that began in 1992….over 20 years it has expanded its range to include developmental epidemiology more generally: not only the development of psychiatric and substance abuse problems but also their correlates and predictors: family and environmental risk, physical development including puberty, stress and stress-related hormones, trauma, the impact of poverty, genetic markers, and epigenetics. Now that participants are in their 30s the focus has shifted to adult outcomes of childhood psychopathology and risk, and early physical, cognitive, and psychological markers of aging.1

They followed people from the following part of the world till their 30s:

The screening sample consisted of 4,500 children, 1,500 each aged 9, 11, and 13 years at baseline.

They followed these kids over time to see what happened with their health—including psychiatric illness—till their 30s. What did they learn about psychiatric problems? We might have a little something to learn from SantaCon. What if there were an underlying factor that explained the range of (theoretically different) outcomes we observe?

Caspi and Fonagy2 have argued that the best explanation for the psychiatric problems we observe is not a series of wild surprises. Instead, there is one problem—an actual root cause—that drives all the varied presentations of psychiatric illness we have tried to categorize into a variety of disorders historically.

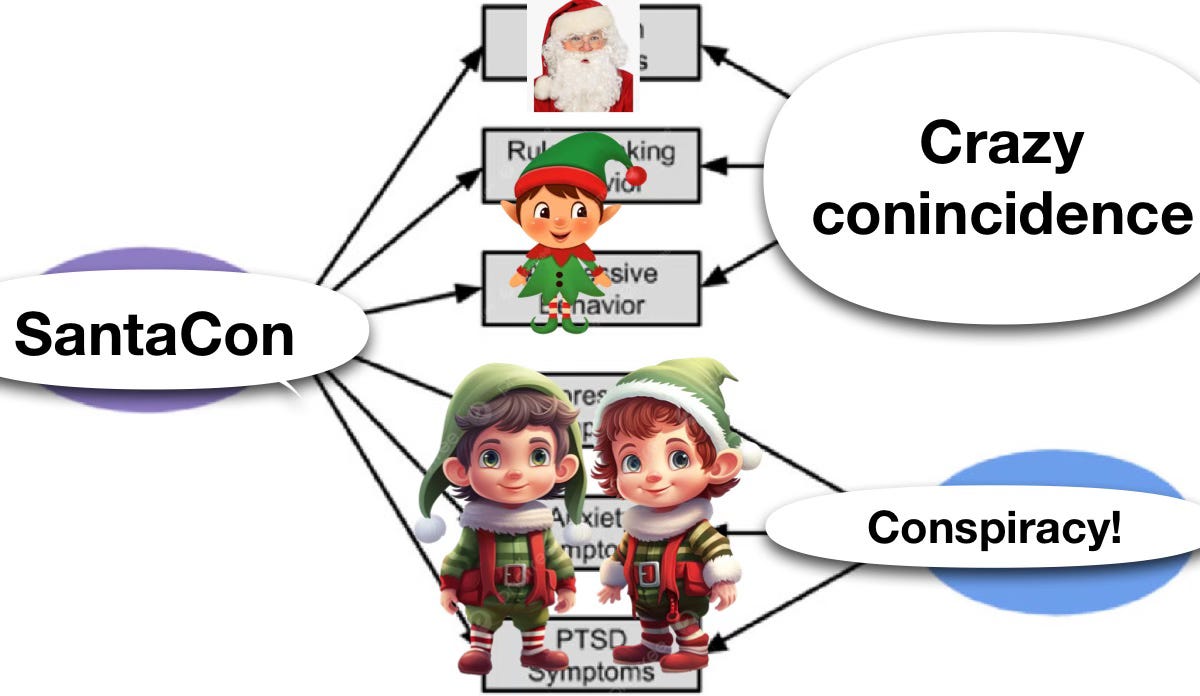

Let’s use Santas and Elves. What does the data suggest is the best explanation for what we observe on a day in December on the Lower East Side of Manhattan?

Could we imagine alternate models to explain the preponderance of Santas and Elves?

The factor analysis approach—what math, based on observed data, predicts the best array of underlying factors? Does a “crazy coincidence best explain some Santas and Some Elves” plus another elf cohort explained best by a “conspiracy?” No, of course, on factor—a day on which people agree to dress up as Santa and go drinking explains the movement disorder, the outfits, and the crowds better than multiple explanations. It’s the reason we have statistics—including causal inference in statistics. (Amazon affiliate link).

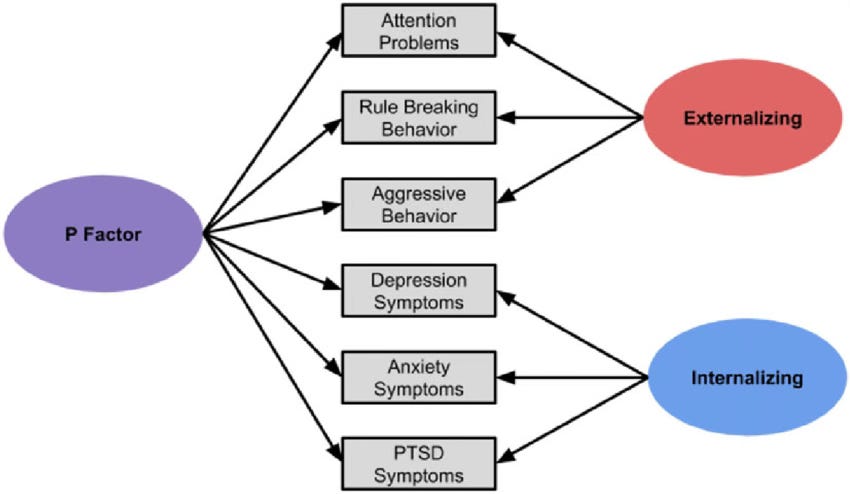

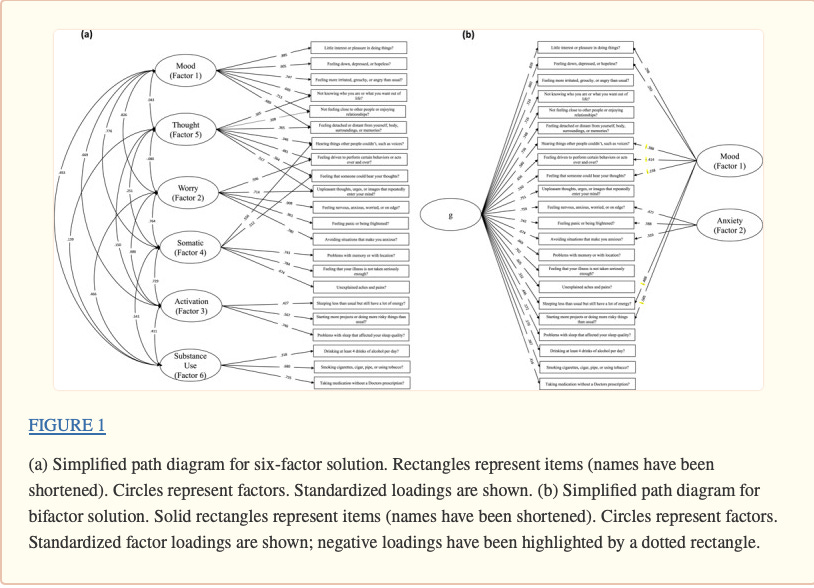

We can use the same approach as psychopathology. Let’s take a look. In the middle, we see the different symptoms (from the GSMS):

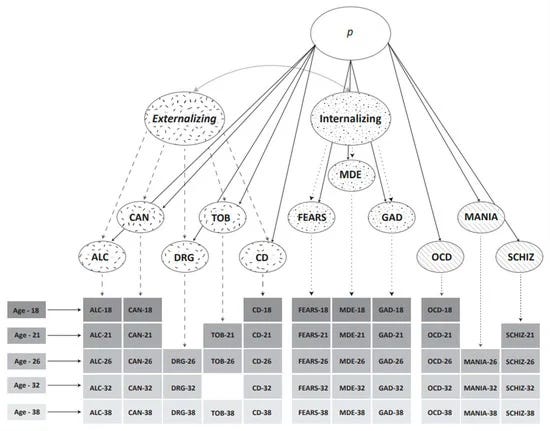

We can ask if a two-factor model (there are two underlying problems) is (or is not) a better model fit than a single-factor model, which Caspi and Fonagy called the “General Psychopathology Factor” or the “P factor.” What they found matters, for how we think about problems of the mind.

What Caspi, Fonagy, and others have argued—persuasively, to your author—is that the best “model fit” for psychiatric problems, over time, is that a single measure, “the amount of psychopathology” or “how sick someone is” is a better predictor than individual (myriad) diagnosis over time. A high “sickness” burden predicts subsequent “sickness” better than “schizophrenia predicts X outcome later.”

Maybe the different diagnoses we see—bipolar disorder, depression, substance use disorders—are better understood if we stratify by severity? Could there be cohorts of very sick people, sick people, and not-very-sick people? And the diagnostic label might mean a lot less than the level of sickness—the P-factor?

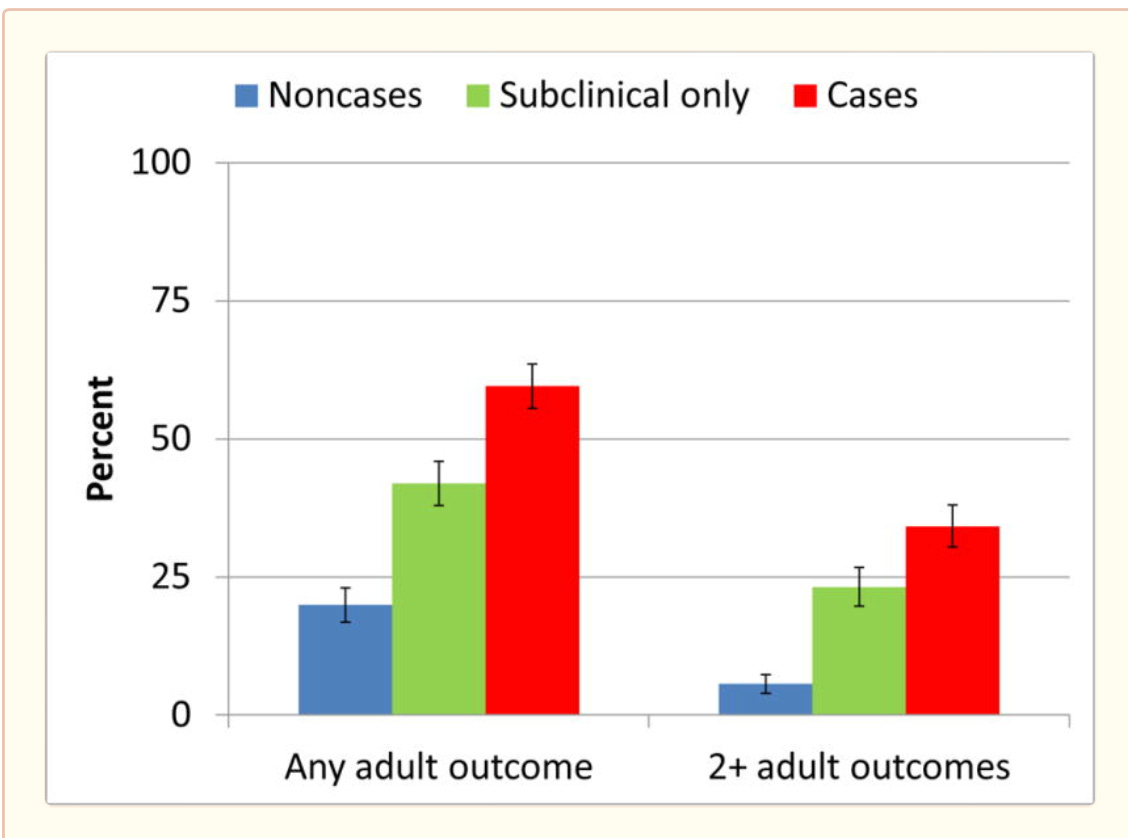

If we have treatments for sicker people, we’d want to deploy them to people who need them. We have some of those3, plausibly—like mentalization-based treatment, for example. In the following graph, we see the outcomes of kids with diagnosable psychiatric illness (red) vs milder symptoms (green) vs. kids without psychiatric illness (blue). We see more problems—general medical and psychiatric!—over time in adults who had psychiatric problems as kids. More bad outcomes are best predicted by psychiatric illness in childhood.

Factor analysis helped us understand what is occurring over time! We even have tools we can use—right now—like the DSM-XC (also known as the DSM-5-TR Level 1 Cross-Cutting Measure). It turns out this tool, developed as a screening tool, might also measure this “P-factor.4” It’s worthwhile to consider—our measurements frame our thinking. I will advocate that we consider our measures as seriously as the outcomes we hope to achieve.

Thanks for reading. I’d like to note, Carlene MacMillan, MD is the human in my life, as well as at Osmind, APA, CTMSS, AACAP, CMS, NQF, and in other leadership roles as well who has pushed these ideas forward in my life and the world.

Costello EJ, Copeland W, Angold A. The Great Smoky Mountains Study: developmental epidemiology in the southeastern United States. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016 May;51(5):639-46. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1168-1. Epub 2016 Mar 24. PMID: 27010203; PMCID: PMC4846561.

Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2018). All for one and one for all: Mental disorders in one dimension. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(9), 831-844.

Nolte, T., Campbell, C., & Fonagy, P. (2019). A mentalization-based and neuroscience-informed model of severe and persistent psychopathology. The neurobiologypsychotherapy-pharmacology intervention triangle: The need for common sense in 21st century mental health, 161.

Gibbons A, Farmer C, Shaw JS, Chung JY. Examining the Factor Structure of the DSM-5 Level 1 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measure. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2021 Nov 16:2021.04.28.21256253. doi: 10.1101/2021.04.28.21256253. Update in: Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2022 Nov 1;:e1953. PMID: 33948606; PMCID: PMC8095225.

Thank you for this piece and for the acknowledgment at the end. I also saw some elves out and about at the Horizons psychedelic conference last week so they have at least two days to be out and about in NYC.