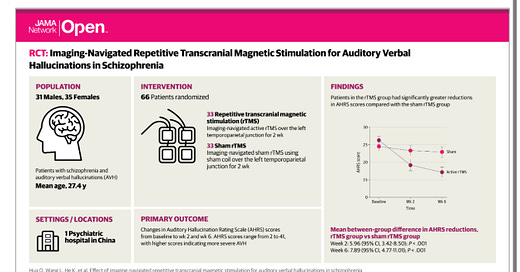

Treatment for Auditory Hallucinations in Schizophrenia Without Drugs?!?

A randomized controlled trial of rTMS in schizophrenia offers new hope

Hot off of Wednesday’s coverage of the novel oral schizophrenia treatment Cobenfy in this newsletter—hailed by my reader Chris Aiken, M.D., as “brief”—we have yet more good news. The serious exploration of transcranial magnetic stimulation for schizophrenia dates back to the late 1980s and early 1990s. I remember, when I was 20 years old, chatting with a fellow research subject at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, while we were both enrolled in clinical trials for the exploration of our illnesses. I was enrolled in a trial—that would involve a lumbar puncture from J. John Mann, M.D.—on bipolar disorder, while R. was there for his his schizophrenia.

For those new to the topic, a little bit of science review: transcranial magnetic stimulation is a technique that uses changing magnetic fields to induce neurons to fire in the brain. The firing pattern can either speed up or slow down neurons. We call these stimulation patterns “faciliatory” if they induce more firing or “inhi…