The Problem With Scientists' Explanations of Science

We are careful communicators, which is a feature... and a bug

I’m reporting from Kobe, Japan. This is the location for the Brain Stimulation biannual meeting. Brain Stimulation is an academic journal with the remarkable Mark George, M.D. as its editor. Welcome to The Frontier Psychiatrists Newsletter—a publication that strives to write for general audiences, while communicating meaningful, complex information about the challenges of human suffering. This article is about how to make science more understandable.

Mark George, M.D. the creator of rTMS as a treatment for depression. His a passionate advocate for these new treatments for human illness. He’s also a scientist, and this is a science conference. Here is a brief clip of what exciting content sounds like at a science meeting (I am not identifying the speaker, cause that is not the point—it’s 30 randomly selected seconds):

This is not to say that our Science is not exciting. It’s just not…regular people exciting. It’s not the kind of claw machine exciting my daughter, Quinn, finds very exciting. I’m gong to show that, cause it’s cute:

Science is, as my daughter would have it, Boring! I don't think it’s boring. Everything daddy likes is boring, according to Quinn. The thing is…I don’t think she is wrong, when it comes to the general public’s tastes.

Cautious language does not win a fierce debate. It does not make for a spicy podcast. Science, as a career is really great for people who are slow motion degenerate gamblers. We perform experiments that…might not work! We could spend years on one gamble of an experiment—and it could change the world…or not.

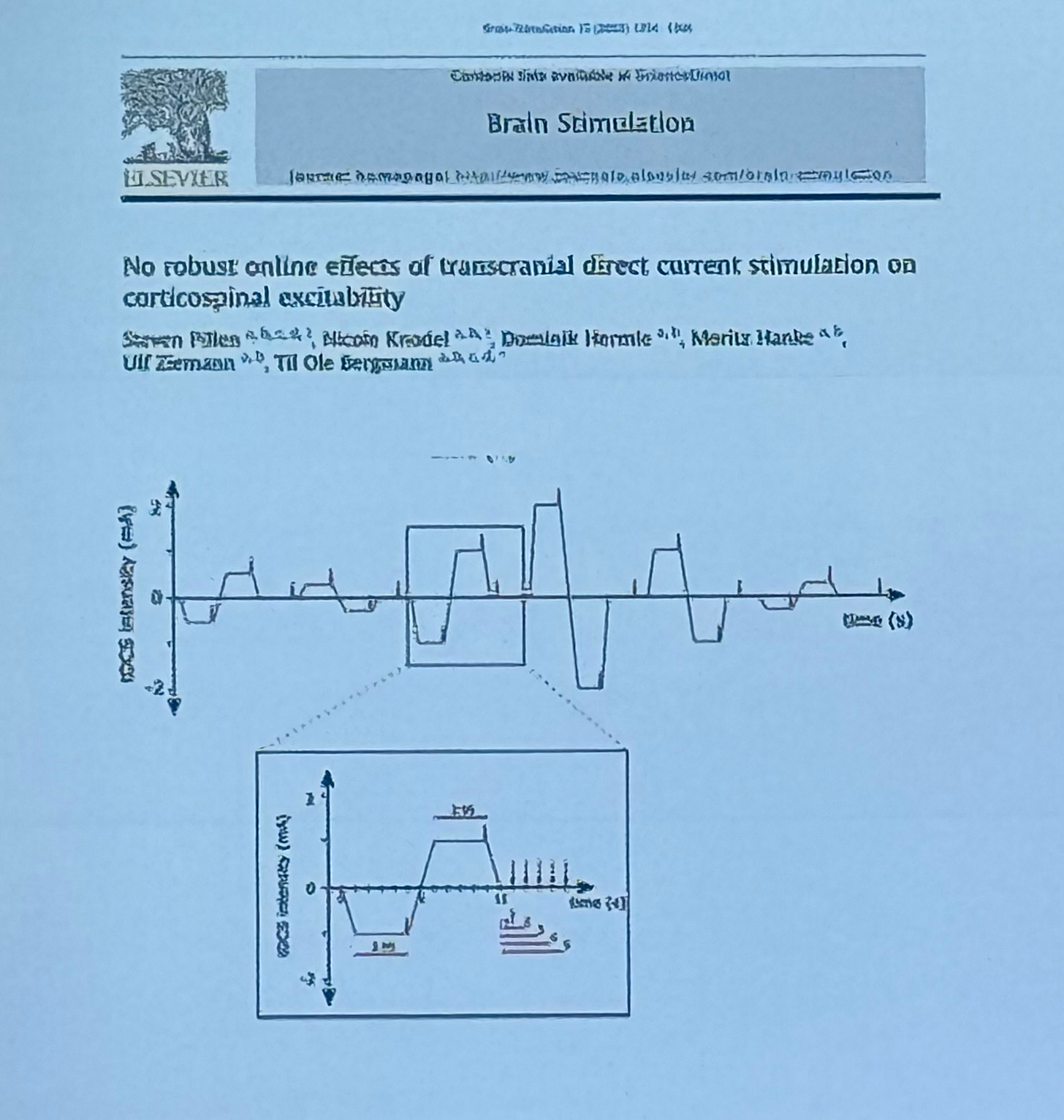

You could spend your career on groundbreaking science, only to publish findings with titles like…this:

“No robust effects…” isn’t the kind of finding that gets more funding, no matter how scientifically important. Gambling at a casino had the benefit of letting you know if you are a loser that day. In science, you can ruin your entire life’s work with one finding only a decade later! It’s only for the most edgy, risk-obsessed individuals…who generally speak in an even tone.

How, then, can we communicate effectively to the broader world, so we don’t bore our fellow humans to death? We also don't countenance the communication of inaccurate information.

I’d argue—entirely self-servingly, as a communication to the public of science ideas professional—that a possible way to bridge the gap is for scientist to practice storytelling and persuasion, in writing or even other, popular formats.

I’m heartened to see NEJM recently partnering with the comedian-scientist Dr. Glaucomflecken. He’s a gifted communicator, and funny, which makes him relatable. He makes funny little videos. But—and this matters—millions and millions of people watch those funny videos. They are masterpieces of efficient communication.

The NEJM—one of the highest impact factor journals in science—has partnered with an internet comedian. You know, to get the work out in a way anyone would care about.

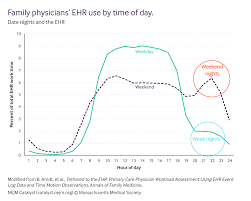

The NEJM and other publications have also started to include very short form almost Meme style infographics. This is the idea! For example, this is a recent NEJM infographic about how much time family med docs are spending on the EHR…

It gets the point across quickly. My challenge to academic journals, and to the scientists who submit to them—what if we required not just the article, but a funny video or catchy meme that could explain the main point of any given paper concisely and convincingly? The harder we train as explainers, and story tellers, the better we might be at getting the understanding of our work to the world. We could also allow short story, poem, song, limerick, or other formats!

Let’s get explaining what we do! And perhaps— even—having some fun with it!