The Passion of the Medical Loss Ratio: Why Hath Payers Forsaken Mental Health Treatments that Work?

How broken incentives created a system of endless torture for the most vulnerable…Part 1 of 2

The Christian tradition talks about the concept of “original sin,” which becomes the basis for why our western tradition’s leading man—Jesus— had to die in such a dramatic way for the story to have real forward momentum.

As scholars of the biblical story of Jesus, some have chosen to focus on the suffering he endured in the peri-crucifixion period. The psychological pain— how much it would suck to know one was forsaken by God when he’s your dad—was understood as the bad part. Others focused on a more corporeal “snuff porn” take on His crucifixion. Both groups agree, this experience—“The Passion”— sucked. This is Jesus —in some version of “the Summer of 33 AD’s SAW prequel”— dying for our sins. And Lo, our sins were thusly forgiven. Not ones to waste a “safe-harbor” loophole, health care regulators and politicians have replicated this “thou art forsaken” experience with a growth trajectory the envy of every YC grad.

Crucifixion is a grim business. It reminded the enemies of Rome of the price of disobedience. Even the involuntary schlepping of the horizontal beam of a cross on one’s way to one’s execution was the “co-insurance” of its day. The almost-crucified were expected to bear the burden and spare the Centurions. But there’s an important point about crucifixion, which makes it a palatable option when compared to the suffering of “the patient journey” in psychiatric illness: the crucified know the suffering will end. It’ll be a couple of days, and then …you get to not have to feel that way anymore—predictably. Not that death is a good outcome for the crucified, but you generally had a good sense of where things were going, and the intent of the parties involved. As Shakespeare notes In Macbeth (Act I, Scene II):

If I say sooth, I must report they were

As cannons overcharged with double cracks, so they

Doubly redoubled strokes upon the foe:

Except they meant to bathe in reeking wounds,

Or memorize another Golgotha,

I cannot tell.

But I am faint, my gashes cry for help.

This is, of course, an allusion in the beginning of the play to the place—Golgotha—where Jesus was crucified. Even in one of the bloodier Shakespearean tragedies, this is not understood as a scene to re-create.

Ignoring the lessons of history is as reliable as play writes cautioning against it, however. In our modern health care system we have done so, and added the indignity of getting snail mailed a bizarre parody of a bill called an Explanation of Benefits (EOB) at the end. To wit:

Explanation of Crucifixion: (EOC)

The Following is Not a Bill

Crucifix Procedural Terminology (CPT) Code: C666

Dx Code: M33.2 (Messianic Personality Disorder)

Place of service: Golgotha

Billed amount: 100 silver.

Allowed amount: 50 silver.

20% Co-insurance: 10 silver.

Your plan rendered: 40 silver.

You may still render unto Caesar: 50 silver.

And you thought The Passion was bad? Imagine going through hell and back—literally—and this is in your papyrus inbox!

It is at this point that I would also like to get credit for being able to quote Macbeth in two separate mental health think pieces!

To suffer in silence or worse, loudly but unheard, is tragic. To be denied care that might be helpful when in the pit of despair? This is The Passion of the psychiatrically suffering. I’m presenting the hypothesis that people are forsaken because…it makes a complex balance sheet work. It a trespass against us. The experience of care for under-treated depression or misdiagnosed schizophrenia is horrifying. The fee-for-service insurance system is a system of unoriginal sin — in our case it’s a cynical implementation of an attempt to limit the optics of profits. This is done with centurion-stoic disregard for unintended consequences. The business model profits on suffering. This would predict “more suffering.” And it does. And we do.

Now, if you were thinking: “Dr. Muir is a little messianic” with this glib comparison of psychiatric care and crucifixion of the Lord Christ, consider: The crucified were often stabbed or had their limbs broken to hasten their painful death …as a service. That mercy—harsh though it may have been— is only a fantasy for those suffering under the current standards of care. 45,000 people kill themselves every year in the US because they would, in a dark enough moment, rather die than live as their illness dictates. In Rome, the passing throngs mercy killed people left to die by asphyxiation. Yep. It is with a grim sense of irony I note: this is still a common way for vulnerable people—often mentally ill—to die at the hands of the state. In the US, instead of help, we trust those in despair to just kill themselves already. For scale, the number of completed suicides annually is more every single year than we’ve ever had in a research study on suicide or depression.

Jesus had to wonder why he was forsaken. Those suffering now get that answered for them every time they seek care. They are “not a good fit for the practice.”

Our cruel Caesar? I am speaking, of course, of the Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) for private health insurance.

Even that name probably tells regular folks nothing about what I’m talking about, and that’s kind of the point. It is so boring you might have already had a false positive on a sleep-latency test just reading those words. Try it: Medical Loss Ratio. Medical Loss Rat-snooooore. It’s like counting sheep.

And yet, I will argue, the incentives created by this system lead to the prolonged and predictable suffering of millions. Decades of despair, overdose, and death is it’s due. The MLR insures—get it?!— suffering on a scale that would make Rome’s Professional Crucifiers Association blush.

To make this less boring I’m going to use a metaphor. To avoid being cool, I’m going to use a really dad one. It also lightens this article up quite a bit, which, after opening with Mel Gibson’s torture porn obsession, is a welcome palate cleansing sorbet. Or, in this example, ice cream:

The Passion (Fruit Scoop) of the Ice Cream Serving Size

I have twin six-year-olds. If there was a regulation around how much ice cream they could consume, and it followed the same math as the MLR, this would be a Sunday conversation with my kiddos:

“Trent, Quinn, come here. It’s time to have some ice cream. All of the adults have had a conversation, and we’ve decided it would be inappropriate for you to have the appearance of too much ice cream. So daddy has a rule—Quinn, put that spoon down— about the amount of ice cream you can have.

“You can’t stop us from eating as much ice cream as we want!”— Trent, lobbying effectively.

“You are correct, young man. Practically speaking, I can neither limit the amount of ice cream you’re going to want nor can I keep you away from eating as much ice cream as you’re going to. I mean, I could. That would be good parenting. I could make adult rules for the total amount of ice cream, or create other regulatory standards. But I’m not gonna do that. Because I don’t want to hear you complain, or in grown-up language, lobby. What I can do is cynically control for other people thinking I’m a terrible father. So I’m going to limit both of you could be eating…only 20% of the ice cream in your bowl.“

“But how much total ice cream can we have that fractional amount of?“ Quinn asks, with frankly, disturbingly mature verbiage.

“So that’s the thing, you can ask for any total amount of ice cream you’d like. In fact you can ask for incrementally more ice cream every time. Every bowl can have as much as ice cream as you can spoon out. But you can only complete 20% of any given bowl.”

“Is there any limit on total number of bowls?” asks Trent, with growing suspicion. After all, we had the “things that are too good to be true” talk just last week!

“There will not be any limit on number bowls. This is America!” I respond, patriotically.

My children work out that asking for more ice cream is THE correct answer to allow maximal gorging on 20% of that amount.

“Maybe keep in mind how permissive I am now when you are choosing old folks homes one day?” I mutter.

“That would be undue influence!” says Trent, who clearly has been learning to read at a pace that I have not understood until just now.

I trust this is likely to be both the first and, God willing, the last time that twin 6-year-olds were used to explain the medical loss ratio.

In their childish innocence, they highlight the fundamental problem: if you can only ever make a 20% profit margin, and you still want to increase profits, you need to increase both premium costs and what you spend on care. Or, as Trent later put it,… “Daddy… My tummy really hurts… But can I have some more? If I have some of your Pepto-Bismol daddy, I can accomplish a little bit more ice cream eating!”

Kids, at least those who are being scripted by their physician parent with a healthcare economics axe to grind, say the darnedest things!

Let’s Play Pretend!

Blue Cross, United, Cigna, Aetna (BUCA for short) Anthem, Magellan, Oscar, Elevance, Evernorth, Optimus Prime—and other carrier names following that pattern will pretend to want to save money all day long. The fiction of “controlling costs” never gets old. It’s how the justifying random denials story is told. There may be some segments of the market where it makes sense to save. But overall, any contention that actually reducing cost is what is going to happen is fictional at best and fraudulent at worst. Prior Authorization? It exists to increase total cost through kicking cans down the road till people are sicker—sick enough to need the really expensive care!

The Worst Shareholder Meeting Ever Imagined (BUCA edition)

Dear shareholders—amazing news: we cut costs by 7%. Please enjoy our 20% profit margin of 7% less spending. Keep in mind under a 1% drop in the share price of UHC erases on the order of $4.5b from shareholder accounts. That is more than the market cap of any 2 startup unicorns below #15 on the top 100 list combined.

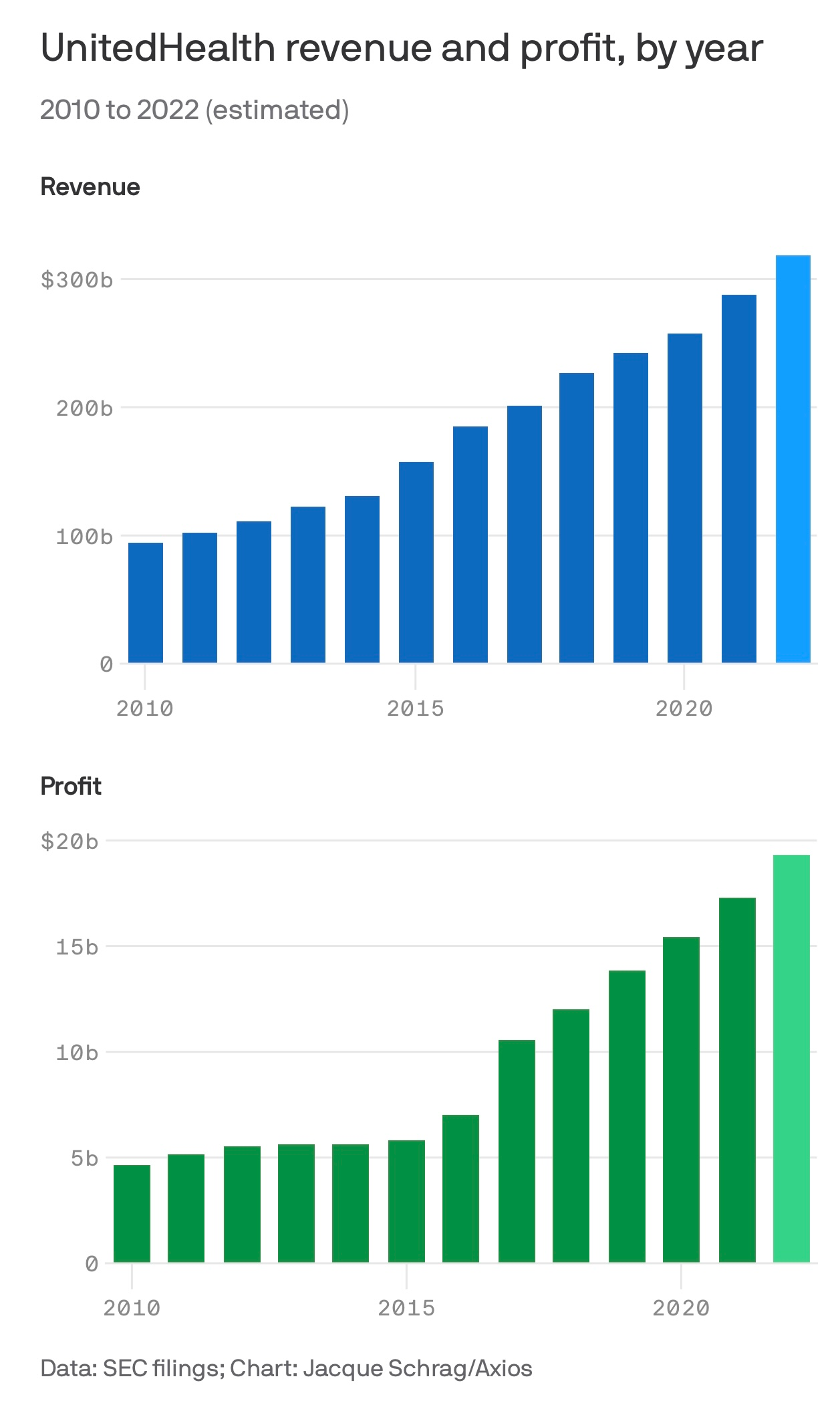

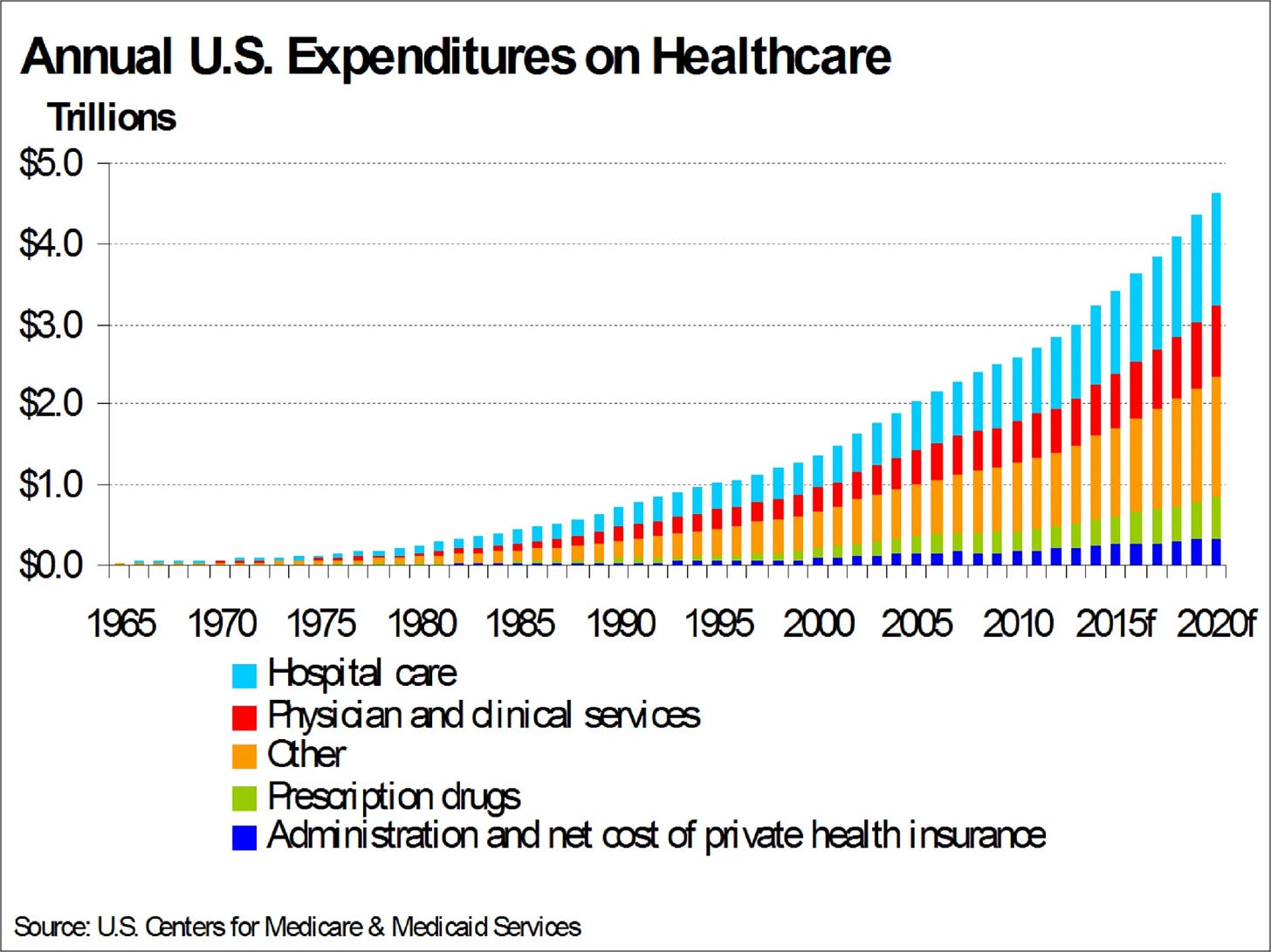

More spending in healthcare is simple. More sickness has to be treated with more care …expensively. This is the familiar trend:

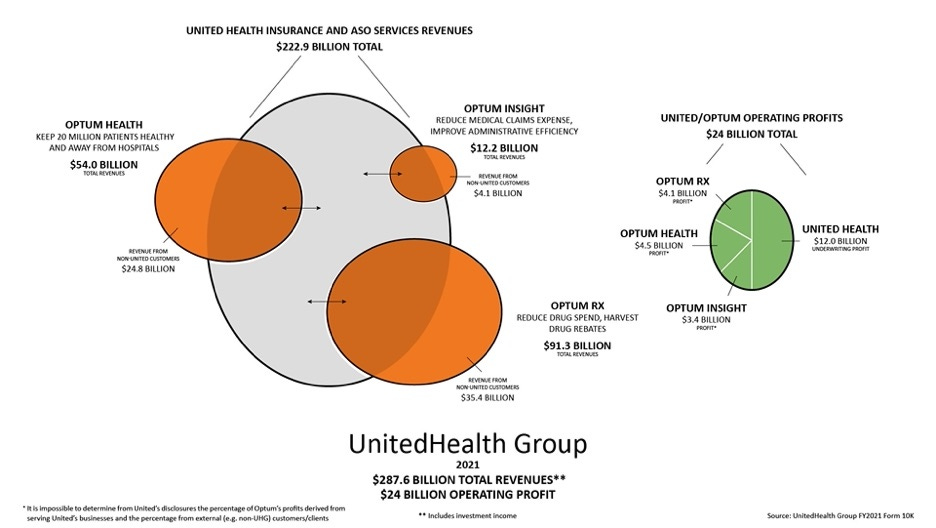

Now before we have to dive down some awful rabbit hole of how the different parts of the UnitedCaremarkNorth Borg interact with each other, I’m going to take as a premise that even if you don’t believe my argument, please accept the premise: anything that increases cost is good. As promised:

Imagine… a mental health system that would only make cost go up over time? Dorothy, you got this:

Basic principles would include:

Everything should require prior authorization—more incoherent roadblocks are better.

The more effective the treatment, the less accessible it must be.

Long wait times are a feature, not a bug.

Financial incentives should drive great doctors away from innovation and insurance panel participation.

Acquisition of endless non-innovation in start-ups keeps founders from disruption.

Relentless focus on low acuity.

Diagnostic clarity is to be avoided, both in practice and in the public discourse.

Don’t talk about Fight Club.

Have the prior two rules be borrowed. See what I mean? Non-innovation!

Moving the paradox forward…to profits!

Now, there are constraints on the above system. One could not simply pay for everything that anyone asked for, because it would increase the cost of doing business so quickly that they would have unpredictable and massive losses. You need to have an infrastructure of dynamic approval and denial of claims in order to perfectly hit the 20% profit margin that you are allowed. Sometimes you need to deny more claims, and sometimes you need to deny less, or you would become too profitable and by law they have to return billions. At the beginning of Covid, this nightmare scenario almost occurred – the very expensive care that is most of elective healthcare in America got shut off overnight, and in the middle of a pandemic, major insurance companies like United healthcare ran the risk of having so much more money come in as premiums that they would have to pay it all back. Citing a remarkable exploration of the structure of Optum and United healthcare:

Hospital finance colleagues reported an immediate and substantial drop in medical claims denials from United and other carriers in the summer and fall of 2020. United’s quarterly profits dutifully and steeply declined in the subsequent two quarters, because its medical expenses sharply rebounded. The rise in United’s medical expenses helped the firm avoid premium rebates to patients required by provisions of the ObamaCare legislation passed in 2010. The firm did voluntarily rebate about $1.5 billion to many of its customers in June, 2020.

This is where the ability to dynamically deny claims or increase the cost for the company by essentially becoming more permissive on what they let through the gate came in to play: the IT infrastructure was able to dynamically adjust so that it paid out many many more claims than it might have otherwise! And now, all of a sudden, the cost of doing business went up so much, that all those extra revenues from Covid premiums unspent became strategically spent on the various business lines that they also own. No real money (less than 1 months profits) had to be returned to the consumer, and shareholders got the returns they were expecting.

Costs have to go up every year, and because there are multiple companies in the space, they essentially have to go up somewhat uniformly across all of the companies. That way premiums for everybody go up some semi-palatable amount every year. You can theoretically comparison-shop between one plan and another but it’s a little bit like the best colleges and universities list. It can tilt backwards and forwards between Harvard, Princeton, and Yale but no one has to worry that UMass will knock them out of the running for the top three spots.

The Breaking of the Fellowship: The End of Part One.

So this has been Part One of my argument. I do not believe there’s a sinister plot afoot. I believe there is a much more unsettling and sinister reality which is that the incentive that is driving the balance sheets of our major payers forces them inevitably in a direction, whether anyone knows it or not, that leads to higher costs, more sickness, more dysfunctional systems, and higher premiums. Rinse, repeat, every year, without end until we are all broke and dead.

Thank you for reading all the way up to the end of part one of my thrilling series of what I imagined to be two parts: The Passion of the Medical Loss Ratio. In the next installment of this piece, I will review the impact on the mental health system specifically, and highlight instances where I suspect the most parsimonious explanation for why things aren’t any good is the above rationale. We will stress test the assumptions, and we will look at fascinating/horrible edge cases.

So consider this part the Old Testament, and the next will be the New. I’m hoping I can pull it off in just the Old Testament/New Testament Substack format — Otherwise I can get in some real trouble making this a trilogy!

Heaven forbid.

—O. Scott Muir, M.D.