The Culture Deck for A Remarkable Outpatient Mental Health Practice.

These are the actual slides from my first company's culture deck, and some photos too.

It was a long time ago. It was a galaxy far, far away. It was before the pandemic and then during. It’s a story for later…but one specific memory for now.

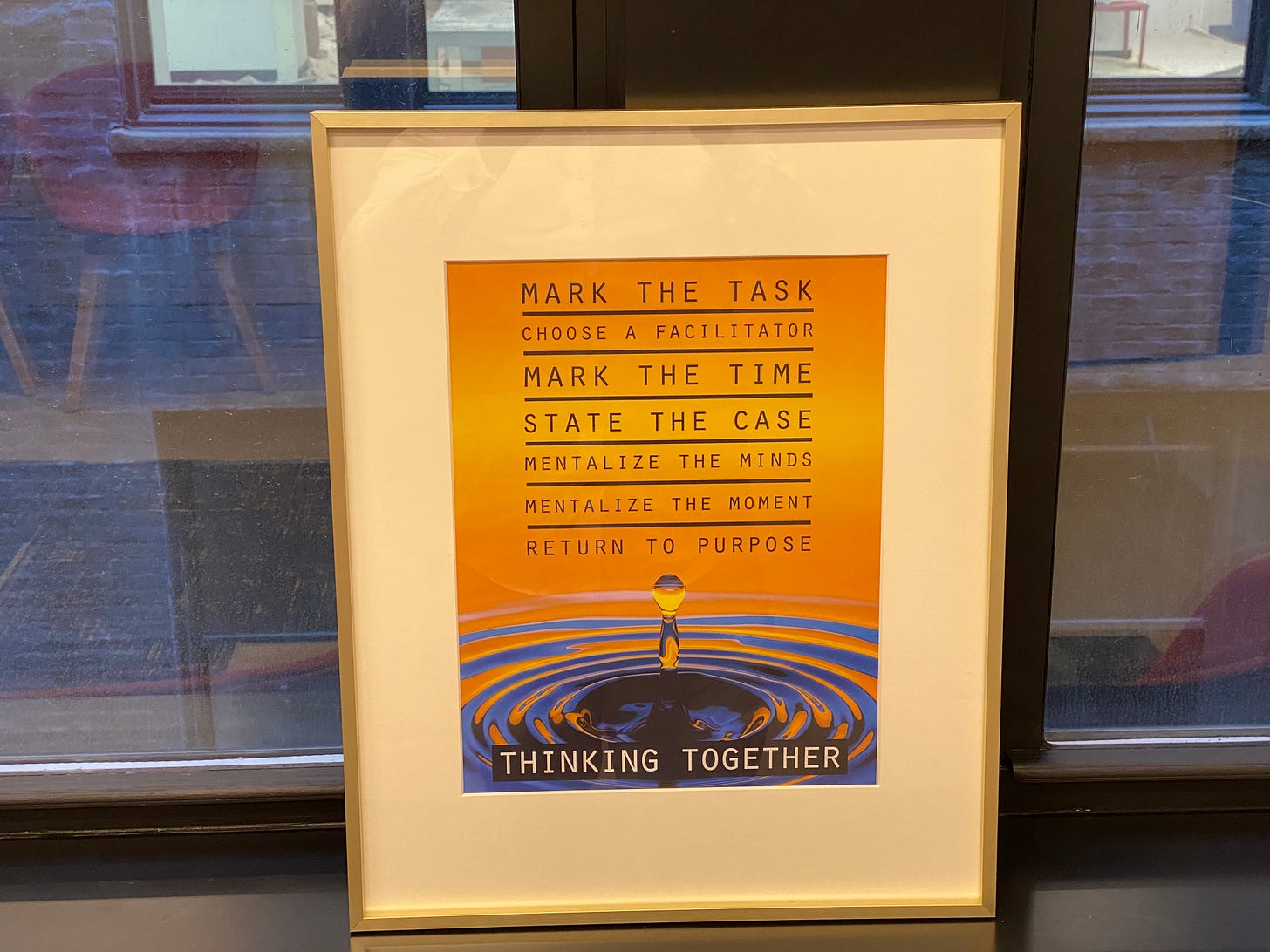

I have interspersed photos of the office in which we worked:

I made the black-and-white “culture deck” to explain the why behind our clinic for the 70+ people on the team. These are the screenshots of the slides they saw. Nothing Fancy.

I wanted to explain to people who came to work with us what was on my mind when I hired them. Many of these individuals did not come from the culture of medicine. The service is the thing.

The culture of hospital medicine is peculiar. It's not the same as most jobs. It can be severe. I didn’t want to be severe, but I wanted to communicate the cultural austerity that physicians went through on their way to this place.

We were doing challenging work. It was an outpatient mental health practice where we screened for suicidal people. We took care of people who were very, very unwell. Trying to do impossible things is not a "traditional day job.”

Many of the non-clinicians participating in the logistics of the operation had no prior experience in healthcare. This job—in some cases, their first healthcare-related employment— was all they knew of medicine.

This slide refers to the experience of being a Psychiatry resident on a call, particularly in my training program. The pager was with the intern on call; they had to carry it always. It was a sacred duty. Everyone in the hospital called that number if there was any problem. And answers needed to be prompt. It could be an emergency. You had to be ready. Never leave the pager. This was taken into my DNA as a physician.

And I wanted my colleagues to understand that urgency. Two things were unspoken, one of which was the archaic nature of the pager, and the other was the trauma that came with always having to be on guard and vigilant. I didn't recognize it then. It seems very obvious now.

I am proud of this slide. Not the erroneous capitalization of the word “sense.” But otherwise, it’s good.

Responding with sense and compassion—I stand by.

Among the broadest and most difficult lessons to live by is stated in the above Maxim. This accountability is the heart of what I was trying to communicate. But, in retrospect, it is also premonitory. I don't run that business anymore. It was sold, and as is often the case, external capital brings in new operating models.

This is not because it was a wild success but because it had to be sold to individuals with more capital. For any company to scale, the ability to raise money is vital.

When it comes to healthcare, and particularly the care of psychiatric illness, the above statement is one that I think also holds up well many years later.

I zoomed in on this little because it's essential. Risk management is what we do for our patients, business, and ourselves.

The final slide in the deck was a cautionary tale when dealing with people who need help; assume they deserve it. But not that they will accept it.

This is what I shared with my team in 2018. Thanks for reading.

I'm so proud of the work that we did. I'm still proud of the people I worked with. The data we are generated continues to drive the field to this very day. But many more people needed the help than we could at that time. And still do.

The practice in which we worked reduced psychiatric hospitalization by 90%. The hard part about that number is we had enough complex decisions related to hospitalization to know that answer. Preventing psychiatric hospitalization might be lifesaving.

I now know a lot more about the risk factors for suicide than most—because we took care of the most suicidal patients.

We kept them out of the hospital. And many more people lived than would have otherwise.

—Owen Scott Muir, M.D.