I've written before about having bipolar disorder. Today's post is about how my colleagues proactively helped me stay well. Welcome to The Frontier Psychiatrists.

I attended a residency program with a unique system for allocating responsibilities. Instead of having senior residents make a schedule, they let each class own the responsibility of deciding who would cover which shift.

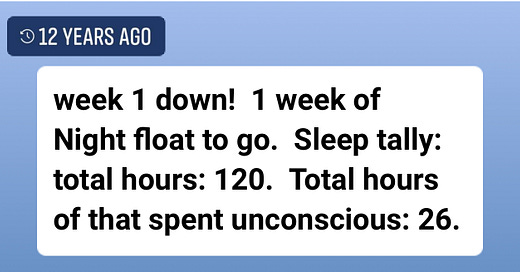

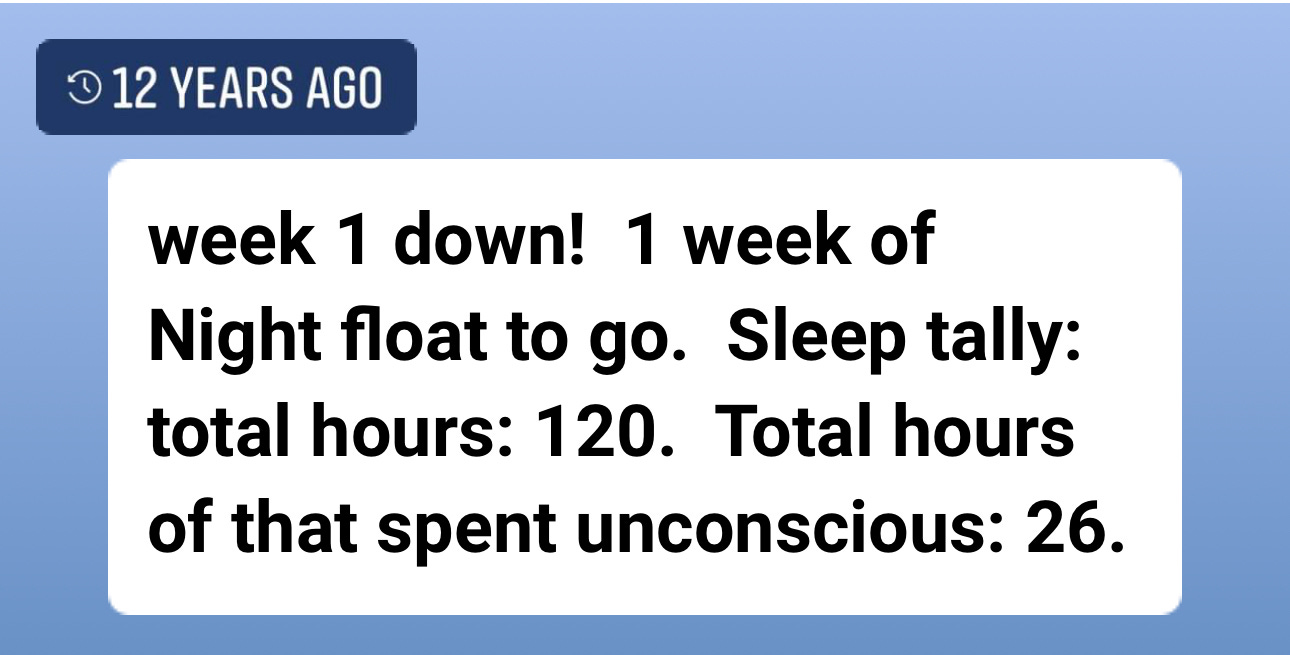

Today, Facebook's algorithm reminded me of the week before my 13 years of bipolar disorder stability and episode-free wellness ended. It had everything to do with sleep:

I've written about sleeping bipolar disorder before, but today's article isn't about referencing data.

That week of night float, we didn't get the schedule ourselves in the second year, the first week of three. In general, during my psychiatry residency, that lack of sleep was the beginning of my mental health deterioration. If you have bipolar disorder, it's a really good idea to sleep at night. It's an even better idea to sleep at …