My Battle Within, Part II

One clinical trial subjects journey through depression, and out the other side.

The Frontier Psychiatrists is not, despite the name, only from the perspective of literal Psychiatrists. The name is a reference to The Avalanches song, for one thing! We love to feature the voices of patients (and other stakeholders) in pursuing human health. This is a newsletter about the frontier, where things are full of possibility. It's not just the old, stale, worn-out hope; it's about new possibilities for how well you could feel. Today, I have part two of a series submitted by a clinical trial participant.

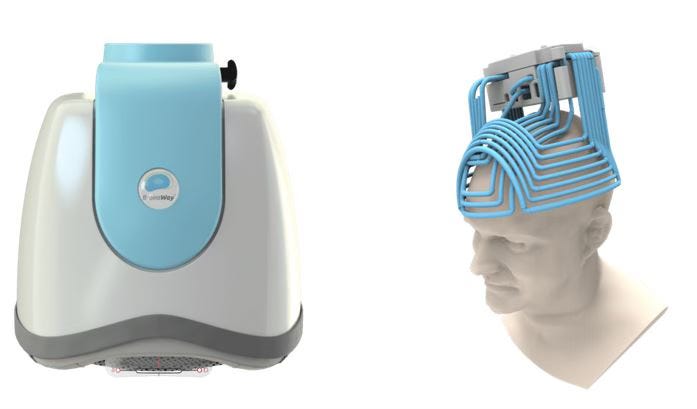

He enrolled in a research study to evaluate the effectiveness of accelerated transcranial stimulation. This is his story, only lightly edited for ease of reading. It’s a dispatch from that hopeful frontier. Jonathan Rosenberg is the author, and his story is, at times, challenging to read. His pain pokes at us right through the words. The story starts with a portrait of Jonathan as a young man, and it hurts to read, even though we know he does okay in the end. I know Jonathan because he enrolled in a study for an investigational treatment. I was a PI. When he asked if he could share his story, I said yes.

Part I is available here. In summary, Jon had been on a long journey with depression in his early 20s. He got through Rutgers, but wasn’t thriving: We know he eventually ended up finding relief as a clinical trial participant with an experimental protocol for depression using brain stimulation. However, how did he get there? What follows is part II of III…Owen signing off, and handing the narrative back to Jon!

About a year and a few months into my job as a customer service representative at an e-commerce toys and collectibles company, I began to feel the hauntingly familiar numbness, detachment, and panic I became familiar with in my first few battles with depression in college. I was showing up for work in January and February but I felt distracted, gloomy, and a shell of who I was just a few months earlier. I didn’t smile, laugh, or exhibit any positive emotions; just a blanket overiding profound sense of sadness. Unresolved customer invoices piled up on my desk, and phone calls began to stress me more and more. I would take my 15-minute breaks and simply sit on the curb staring ahead at nothing in particular and ruminate. It went on like this until early March when I just finally could not fake that I was ok or just going through a manageable funk. I began to miss days of work, and finally, I stopped fighting the inevitable and slowed down to a halt. I forget what I said—the exact words, anyway— to my manager. I’m sure it was like: “I’m going through something. I won’t be coming in anymore.”

From my experience, once the first domino falls and you feel those prodromal

Symptoms—the numbness, the detachment from your family, your friends, coworkers, and environment—It’s only a matter of time before you accept that you are unwell and that you can’t grind away any further. It becomes progressively harder to wake up for work, dress, and motivate yourself to show up, knowing how awful you will be feeling all day. It feels like your battery is 90% drained, and you are still trying to do all the things you are used to doing. Finally, while trying to outrun the coming depression and proceeding as normal as you could muster, you eventually run out of energy and inevitably give in to fighting the rest of the battle at home from the seclusion of a bedroom.

I remember my sister taking me to see my psychiatrist in Hackensack, but I honestly did not have much faith that what was overtaking me could be stopped at this point. My doctor prescribed Abilify and Wellbutrin, and though I was glad we were trying something, I was incredibly doubtful it would work. In the meantime, while I waited day after day, desperate for the meds to work, I stayed home with nothing to do. I did not even have the concentration and motivation to play my brother’s Xbox, which sat unused on the bedroom floor. I remember crying hysterically in my mother’s arms one cloudy day, which I thought was somewhat positive. I knew from my own experience that once the Depression sets in, it becomes very hard to cry or release your emotions. I think Andrew Solomon wrote something similar in his excellent book about Depression called “The Noonday Demon.” (amazon affiliate link). So, when I cried, I did not look at it as a weakness but rather as a last-ditch effort to pump out the pain that was building up in my soul. Sometimes, even early in a Depressive episode, the more intense the crying, the more cathartic effect it has, but the release lasts only for a few minutes. And no amount of crying could drain the seemingly limitless pain, despair, and dread. Admittedly, no cluster of words in the English language can truly describe the agony of severe depression. The genuine feeling is incomparable to any other feeling you ever experienced before. The intensity of the emotional pain is honestly beyond comprehension until you are suffering with it. You can blend all the bad emotional states one goes through in life: a breakup, bereavement, embarrassment, failure, pessimism, hopelessness, and all of that combined is probably not even half of the agony and burden of severe depression. The simple fact that most people suffer from it for months and months at a time is one reason why suicide and disability are higher in “the depression and bipolar II” community than any other illness, including cancer.

Many great authors have tried to describe and identify the pain of severe depression. I think William Styron did it best in his depression memoir “Darkness Visible.” He described it as being trapped in an overheated room, but it’s even more than that. It’s like suffocating from moment to moment. It doesn’t matter if you sit, stand, drive somewhere, or lie down. Or if you’re with family, friends, or alone. You are consumed by the agony of this alien feeling, which only seems real and possible because you are experiencing it. And the deeper I fell into this depression, the harder it was even to shed a tear. It felt like all emotions died in me except intense sadness, hopelessness, distractedness, and anxiety.

Those early days of that depression were very difficult. I missed my coworkers. I missed my normal life. I remember walking around a local park and seeing one of the guys I played intramural hockey with at Rutgers walking with his girlfriend. Maybe it was my slumped shoulders or my sad, disheveled appearance, but he made brief eye contact yet did not say a word and walked right by me without any expression. Though he was not one of my close friends at hockey, I was surprised at his lack of decency and was slightly hurt by it. That was one of the last times I would take a walk for a long while unless it was to pick up food from a nearby restaurant, which was always a major uncomfortable endeavor. Almost nothing gave me motivation to do anything. Showering and shaving were major tasks for me at this time. If I managed to shower and shave once a week, I would consider that a small— yet difficult— accomplishment.

As March turned to April, and the depression set in, I hardly went out at all, except downstairs for a cigarette. During the moments when I just woke up, I felt lost and incredibly anxious in addition to my despair. During these first uncomfortable seconds of each day, I tried to calm myself by rolling off my bed to the other side of the small room and quickly putting on an episode of a TV show in a futile attempt to distract myself. But when I “watched” any show, I could not focus, and I could not truly distract myself from the internal suffering, the swirling ruminations.

“I’m a loser; I can’t survive another episode of this. Why do I have this disease? When will it all be over?” These are some of the repetitive thoughts I had. I stared at the screen while lying down in a distracted daze. However, having “the show on” in the background gave me some measure of time moving forward, one slow minute at a time. Like the song by Chris Cornell, “Doesn’t Remind Me,” I found the show “Deadliest Catch” easiest to watch because it did not remind me of anything that would hurt to think about, like what my friends were doing or what my life was like before this terrible illness hijacked my brain and left me in ruins.

As April turned to May, and the days were longer and brighter, it brought me an added level of despair. People I encountered the few times I was outside were reveling in the beautiful warm weather, happy and enthusiastic. And I felt the complete opposite. Waking up to sunshine when all you want to do is be dead is difficult. For some reason, rainy days were a drop easier for me to endure, maybe because it kept the sun and people away. By May, I lost hope that the medications my doctor tried would work.

My uncle paid to send me to a specialist from Columbia Presbyterian named Dr. P. He took notes of my history and then referred me to a psychiatrist near me in New Jersey. The psychiatrist was in his 60s and had a neat, clean office in nearby Ridgewood, NJ. He was an impressive man—tall, thin, fit, and confident. He prescribed the medication Remeron and, I think, one more medication, which I now forget the name of.

After a month or two of no change in my mood, I completely gave up on the idea that ANY medication could stop this depression. I foolishly stopped taking my medications altogether, hoping that the depression would resolve itself after enough suffering and time passed. May turned to June, and I remember on a Sunday, there was a birthday party for my grandmother Bessy. The last place you want to go amid a debilitating depression is a social gathering with extended family and my grandmothers’ friends at a restaurant. To have my illness on display for my grandmother and all her friends and my extended family to see was uncomfortable for me to endure. Still, the guilt of not going to my grandmother’s 80-something-year birthday was something I did not want on my conscience. So, against my desire, I decided to attend. My clothes were wrinkled and my hair unkempt, and I showed up at least 30 minutes late while everyone was seated at their reserved tables at a seafood restaurant in City Island, NY. I remember walking in, and it was very awkward, to say the least. It felt like all noise and talking stopped just as I walked in, and one of my uncles did not even make eye contact when I stumbled in and greeted my grandmother. I then sat down and did not speak much to anyone. I was physically in a restaurant in New York, but my mind and soul were somewhere else. I could not focus on having a conversation. I did not have the enthusiasm to try and initiate any social contact, but I knew at least I did what I was supposed to, regardless of the added pain of putting my suffering and illness on public display. My uncle’s wife, Mimi, looked at me and told me she also had dark moments in her life. It was nice of her to try to relate to me. My grandmother also mentioned to me how much losing my grandfather in 2003 hurt, and at that time, she did not know how to go on. For anyone who bothered to look at me and engage in conversation, there was only one topic that came up, and that was emotional pain. I still remember standing outside once the meal was over, waiting for the valet to bring me my car, and I overheard my uncle explaining to his Dominican relatives in Spanish that I had depression. The severity of my illness left nothing else to talk about when I was the topic of conversation at all. It was a difficult day, but the truth is, so was the next one and the one after that. And the one after that.

That terrible year, 2011, I watched the seasons change one at a time, in seeming slow-motion from the window of a cage of an apartment in Teaneck, NJ. That year, my family was rebuilding our home in Paramus, so we had to stay somewhere temporarily. From winter to spring, spring to summer, and from summer to fall, I watched as the world moved forward while I remained painfully stuck. By November of 2011, 10 months into that Depression, I was just as distraught and miserable as I was in February. Every night when I was lying in my bed, I fantasized about what I would do and where I would go once this terrible ordeal was over. I told myself I’d have a new life. Maybe living on an island far away. It was the only way to calm myself from the despair and fall asleep. Every night when I went to sleep I hoped that I would wake up cured and saved from this hell and every morning I woke up disappointed and in misery.

During this Depression, I did not have the comfort of alcohol because I would gag when I drank anything hard, and even beer did not go down well. It seemed that my overindulgence in alcohol during my first few depressions left my body in bad shape, and my stomach rejected mostly anything alcoholic I tried to put down. I wasted money on Jagermeister, and I threw up from beer, so I gave up trying to numb the pain. I still woke up in despair. I still rushed to put on a TV show, then lied down and tried to calm myself like I did every day. That was one of the small, desperate ways I tried to survive that Depression. In retrospect, it is unbelievable to me that I wasn’t on a medication that could at least calm the anxiety and panic. Still, I was relatively new to the disease of Depression, and when I spoke to my doctor, the main symptom I talked about was profound despair and hopelessness. As a lesson I learned, it is important to be very detailed when talking to a psychiatrist. They can’t magically know every painful symptom you feel. You need to use language to connect with them and make them understand the totality of your suffering. Anyway, the truth is I gave up on meds by May or June, so I wonder if I would have taken anything anyway?

Sometime in the fall, my friend Adam invited me to a concert to see the Soundgarden. I told my friend that in my current state, it might be awkward for him because I had very little to say at this point unless I was verbalizing my tortured thoughts. He was kind enough to agree anyway. I remember being incredibly quiet that whole night, especially during the drive to the meadowlands and back. It’s not just that my mind was moving slower than usual, but I did not have the energy or focus to have a real conversation. During the concert, I looked at the thousands of people in attendance and wondered why I was the one carrying this burden instead of enjoying the music. I spent the night waiting for the concert to end to get home and not be pressured to look or act like I was ok. I have no regrets about going, and it was nice that my friend was willing to spend time with that shell of myself. Though I can’t say I had a good time, it was a somewhat positive sign that I was at least willing to go out and join the masses in a public social gathering.

Finally, even though I didn’t feel magically cured by December, I had family responsibilities that forced me to be somewhat productive again. It fell on me to help my mother move all our belongings and bring them to our new house, which was finally ready for occupancy. The whole process of moving and then walking into our new home had a positive feeling of a fresh start for me. Little by little, sometime between December and January, the worst of my depression had finally burnt itself out and mercifully ended. When all was said and done, my Depression in 2011 lasted approximately 11 months. In January of 2012, I felt that even though the depression was over, it left a damaging scar on my soul and a chip on my shoulder. Though I was very grateful the pain was over, I was also upset that I went through what I did for as long as I did, and it carried over into my period of remission.

When I talk about my life and disease from 2012 onward, I cannot ignore the fact that after my depression of 2011 ended, I resumed my addictive relationship with marijuana. My bad habit started in college in the fall of 2005 and seemed to continue indefinitely, even through multiple depressive episodes. And though I was in denial about this for a long time, there is no doubt in my mind now that heavy marijuana use complicated the course of my illness. It is possible that had I not chosen to smoke pot every day, I may have had a few less depressive episodes. And every battle takes its toll on the soul. But my mentality about life after this painful, long depression was that my days of remission were numbered, and another depression was likely just around the corner. The odds of having another depression after I already had four was very, very high. So, I thought I might as well enjoy myself and focus on what made me happy. Sadly, marijuana was one of them. Playing roller hockey was my other passion and love of my life, and as soon as my depression of 2011 ended, I was looking to join any and every roller hockey league I could.

By the spring of 2012, I played in a roller hockey league. By the fall, it was two different leagues, one in New Jersey and one in Manhattan, and I was happy, or so I thought. My life was simple, and I preferred it that way. I did not know how much time I had until my next episode of depression, and I was determined to live the lifestyle I chose. That does not mean I did not apply for jobs, though. I still had a degree from Rutgers and was not okay with wasting it. So I applied to many jobs, at least 50, probably a lot more, honestly. Most of them were corporate jobs in the fields of journalism, media, and publishing, and I did not get one interview. Not even an interview. It’s true that the economy was still sputtering after the financial crisis of 2008. Many companies fired workers rather than hiring them. And it’s also true that my resume did not look very impressive three years out of Rutgers. The consequences of my past illnesses already began to extend to hurting my future. My extended leaves—plural— of absence due to my illness left me with limited job opportunities and gaps in my employment history.

I have to admit, though, that as long as I was playing organized hockey and smoking weed at night, I was ok with where my life was heading or not heading. As added protection, I also began to take fish oil supplements every day, and I occasionally began to eat sardines because I started to see positive research regarding Omega-3 fatty acids and depression. The dates blur a bit at this time, but sometime around the fall of 2012 or 2013, I relapsed into a moderate depression. Thankfully, it was not as severe as my Depression from 2011 or earlier, but it was bad enough that I tried a few sessions of Ketamine from a doctor who was among the first to offer it to patients for depression. His office was down on Broadway in lower Manhattan, and since he didn’t want me to drive after, I took a combination of buses and trains to get there and back from NJ. The experience of Ketamine was surprisingly pleasant. It felt like my mind and soul were floating up into the New York skyline, and everything that bothered me was left behind. It was like I was a spirit with no past and no history, and I was just in this middle dimension, enjoying the present. Ketamine temporarily relieved me from the burden of being me. Perception of time was not the same, and when the session ended after about 45 minutes, it felt like much more time than that had passed. As enjoyable as the feeling was in the moment, as soon as I was back in my normal state, I still felt the heaviness of my moderate depression. I tried approximately 4-5 sessions of Ketamine at $250 each until I gave up on it as a cure. I don’t remember when exactly I went to a psychiatrist then, but when I did, my new psychiatrist prescribed Lamictal, and it literally only took a handful of days before I felt better! I was shocked and excited because after my prior experiences with Depression I gave up on meds working for me. Lamictal was as miraculous to me as Cymbalta was during my first depression. I remember calling and texting my siblings and telling them the good news—that I was wrong about meds, that meds actually can work! And truthfully, along with fluoxetine, Lamictal essentially saved me from spiraling further into a more severe and prolonged depression. Finally, I had the hope that depression was not necessarily just around the bend, and I was incredibly grateful.

From that point to the early months of 2018, I was basically ok. My life was far from normal, especially for someone with a college degree. I worked at a takeout restaurant on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, mainly because I could not find anything up until that point when it became available in the summer of 2014. And because my weed habit and love of playing organized roller hockey would not be interfered with by the schedule of that job, I thought it would fit me, at least for the short term. Is it fair to say my priorities were all out of whack from my current perspective? Absolutely. But after the turbulence of my college years and directly after, I guess my expectations for my life had fallen big time. Once I found Lamictal and saw it work I could and should have shifted my priorities and worked to find a career, and not been complacent with the dead end job I was working.

This is where I maybe should comment on the role substance abuse may play for other people with depression or bipolar disorder. I know marijuana use is widespread among people with mood disorders, which mainly manifests itself with repeated depressive episodes. In my heart, I already suspected that marijuana may complicate the progression of the illness, but I was too addicted to do anything about it. I honestly enjoyed smoking marijuana, especially at the middle or end of a long day, but the fact that I needed to smoke every night should have been a red flag for me years prior. The amount of time I devoted to smoking it, buying it, and worrying about acquiring it was time-consuming. Marijuana caused breakups with my early budding relationships, and it caused me to withdraw little by little from the normal life of a 20-something-year-old and live more like a recluse. Working 20-25 hours a week plus playing two hockey games a week should not have been enough for me, but for quite a few years, it was. The fact that I continued working subpar jobs because I was afraid to get drug tested by better job prospects was a tremendous limiting factor in my life. Yes, I loved playing organized roller hockey, and yes I was pretty good at it, but despite the suffering I went through in my life, there was no good excuse to live the way I did. But, when I was high, I would watch TV shows like Silicon Valley, Game of Thrones, and Seinfeld, and time seemed to slow down for me. Being high made the shows and even watching hockey more enjoyable. Getting high also took away the loneliness I sometimes felt at night while ironically contributing to that loneliness in the first place by making me comfortable with living the life that I did.

Another important thing I noticed was that even though smoking seemed to relieve stress in the moments of being high, my ability to tolerate stress when I wasn’t smoking was diminishing by the year. Sometimes, the symptoms we think marijuana helps with stress relief, anxiety, better sleep, feelings of euphoria, etc., lead to reduced stress resiliency, worse social anxiety, sleep issues, and emotional flatlining when not high on the drug. In other words, the treatment seems to worsen the symptoms of the illness, even in remission, and it happens slowly but surely over time. I am not in any position to advocate against smoking marijuana. I smoked daily for 17 years. But for people with coexisting mood disorders, it may be more of a complication than a cure. I am grateful that I have not smoked in about two years, and for certain, my anxiety, especially social anxiety, has improved tremendously.

That is the end of part II! Stay tuned for the final chapter in this three part tale tomorrow!