I’m a child, adolescent and adult psychiatrist. I’m also the only physician in my family— sometimes I get questions, and I want to do a good job on them, because it's people in my own family asking.

It turns out, I think a little bit differently about answering a question from someone in my own family than I do when I'm writing an article. The articles I write are intended for general audiences, and so I'm keeping in mind people who have the problem, and people who don't have the problem. I'm thinking about payors when I'm writing this newsletter. I'm thinking about physician colleagues, and I'm thinking about the individuals affected— all at once.

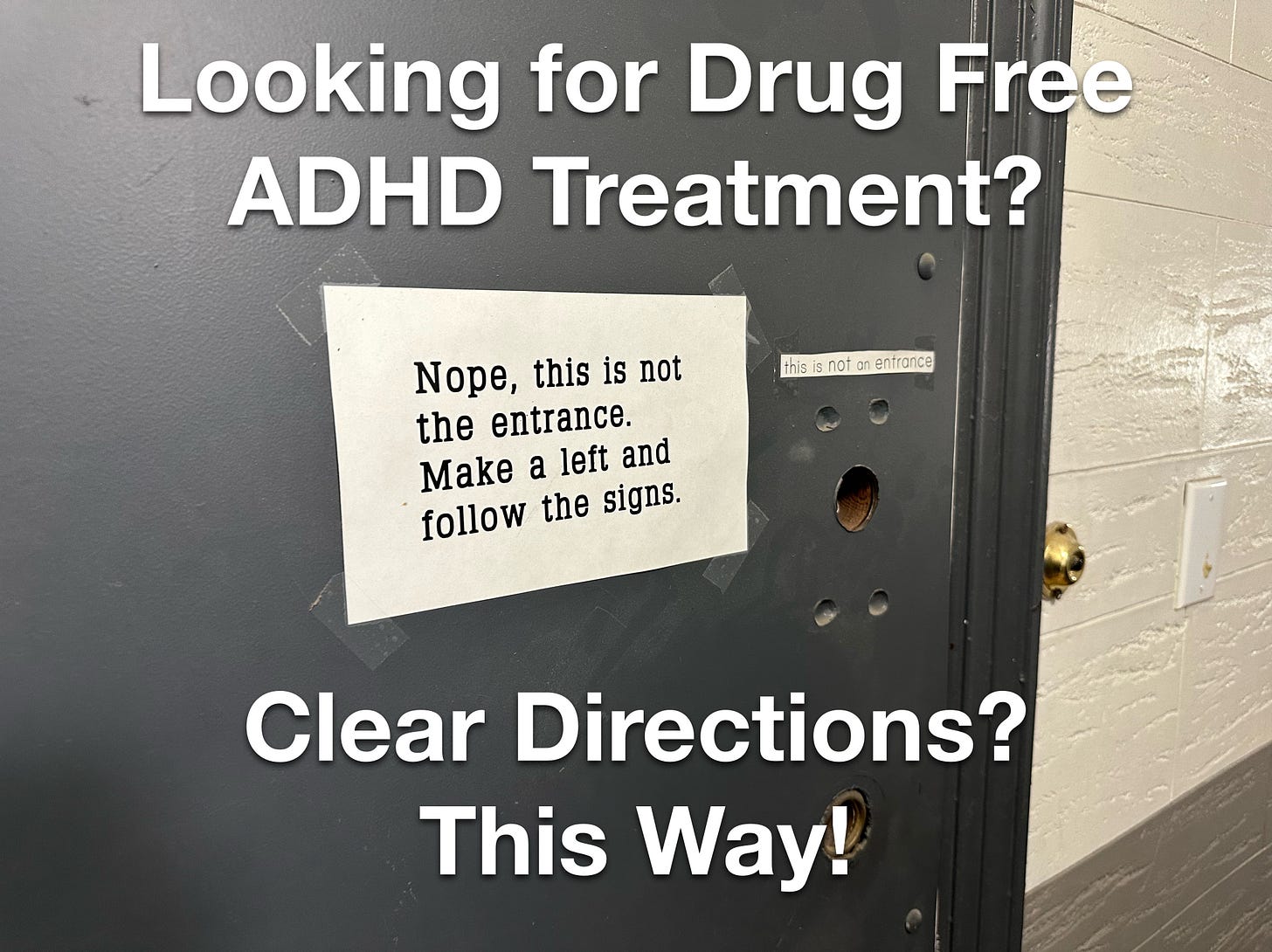

Today's column is written very specifically to the audience of one person. It's a person in my family. Her kid has ADHD. What follows is my advice.

The first, and most important piece of advice, is that this is one of the most treatable conditions that exists. People who have ADHD have the benefit of having a disorder that can be very disabling when it's not identified, but, after it's been identified and treated, can lead to remarkably good outcomes. Your kid is most likely to do great.

It can also be really scary to think about giving your kid medicine. Let's dig into that medicine question. The first thing to know is that not all treatment for ADHD is medicine. We have both neuromodulatory treatments—the monarch eTNS device, for example, which I consider a first-line treatment, and so does the FDA—and medication treatment. The medication's work. They work really well. There are some of the best treatments we have for any condition and all of psychiatry. So everything else you've ever heard of my medical specialty doing? None of it is anywhere near as good as our treatments for ADHD are. They are remarkably effective. They are relatively safe. I will break that down in detail below.

We're gonna get into the safety question more, because it matters.

But the most important thing to keep in mind while you're hearing this whole explanation? It is that the person who's giving you the explanation has the very disease that we were talking about. I have ADHD also. I've had to make the same decisions for myself, for my own health. AND I'm intact enough that despite having ADHD that I'm able to give this elaborate explanation about ADHD to you. Which means, it's not that bad. It's not a walk in the park. Maybe it would be nicer if your kid didn't have ADHD.

I'm not actually convinced it's a disorder. I am more convinced that ADHD is a different brain, that is adaptive in some contexts, and an impairment in others. It's a little bit like living in a snowy mountain town, but only having a sports car to drive. It's gonna handle terribly in the snow, and you're gonna think you have a terrible car, and all your friends in Subaru are gonna make fun of you, but all of that would change if you suddenly found yourself in LA. It's a context dependent disorder. ADHD existed very high prevalence in the population because, for humanity, it's a benefit to have some of it around. I’m going to repeat this argument below, with different metaphors, on purpose.

Untreated ADHD is dangerous. It's dangerous because kids who have it have all the problems that already led you to bring your kid to the doctor. They have problems in school, they can have problems with friends, they can have problems at home with the family, they can lose things, they can have emotional meltdowns, they can be more at risk for drug addiction, they can be more at risk for accidents, they can be at risk for all sorts of badness.

Treating ADHD meaningfully modifies these risks. It reduces the risk bad things happening. So when we treat ADHD, we improve the quality of life of the individuals we are treating. There is some risk of treatment. But the risk of not treatment is greater than the risk of treatment. That's the bottom line, for all the risks of treatment, even with stimulant medication as the only thing we're using, in the thought experiment, it's still safer for your kid to treat their ADHD with the most dangerous medications ww can find then to leave it untreated.

There are other treatments, as I already mentioned. There are psychotherapeutic treatments, like organizational skills training, which is helpful, just not for core inattention symptoms. There is neuromodulation, like Monarch eTNS—again, the detailed breakdown to follow. There is absolutely more effective treatment coming. There are treatments in the pipeline that are not here right now, like low-dose LSD for ADHD, probably TMS for ADHD, maybe even transcranial focused ultrasound, we may get fMRI-EEG neurofeedback, I don't actually know. I do know there's likely to be more in the future.

However, even if we were left with only stimulant medications, the other thing that's true is that as your kid gets older, their brain is going to develop, and they're going to grow out of a lot of these symptoms. People with ADHD get better over time, because the development of the brain addresses some of the symptoms that are so problematic right now. Kids have to grow up. Kids with ADHD have to grow up with a bit more pressure from all of us as we watch them stumble their way through their childhood, while the adults in their life bite their fingernails. However, despite our anxiety, brain development does meaningfully address deficits in ADHD, and that requires time.

Another thing that's important to know is that that burden of ADHD and adulthood is proportional to the burden of ADHD symptoms in childhood. It follows that treating ADHD and childhood, which reduces the burden of ADHD symptoms, leads to less ADHD symptoms later in life. We don't have extremely rock solid data to back up this line of reasoning with long-term prospective studies that demonstrate causality, mostly because it would be unethical to do so—you can't randomize kids to not give them treatment that we know is helpful over the course of many years to answer a question that's interesting and important but would be detrimental to kids in the placebo group. So we're never gonna have the rock-solid causality answer, we're only gonna strongly suspect that the treatment that reduces symptoms is good in a long-term.

Now we're gonna get to the long-term risks of the medication. These exist. They are real. They are less important, I'm arguing, than the risks of the untreated ADHD.

Let’s start by defining some ADHD related things, like :

What is ADHD, Anyway?

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is something I see regularly in both children and adults. We will learn:

What is ADHD?

What are the problems with the diagnostic process for ADHD?

Do you need fancy testing to tell?

Does psychotherapy help for ADHD?

What biological treatments exist for ADHD?

What’s the deal with stimulants?

Do we need to be terrified of dangerous controlled substances?

What else works?

I will begin by establishing up my credentials to speak about the topic, because a lot of fakers have opinions, and it's hard to know what to make of them.

ADHD is included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders. I’m on a committee for continuing medical education created by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP). We make the “Clinical Essentials” trainings through AACAP, and I have the pleasure of narrating the official training on ADHD through that professional society!

My wife, and sometimes coauthor, Carlene MacMillan, M.D. is the chair of the AACAP consumer issues committee, who created this official ADHD resource center for families.

I also, as a human, have ADHD myself.

If that isn’t “rolling deep” on ADHD and its treatment, to you as a reader, I never want to meet you in the back alley of an academic medical conference. I'm pretty sure I'll get my ass kicked by someone with more ADHD credibility. You know, because the multifactorial relationship between impulsivity and violence in people with ADHD. It was originally understood as a disorder of childhood. It persists into adulthood with varying degrees of impact and impairment. ADHD has a long history.

I don’t necessarily consider it a “disorder” in the most common sense of the word":

It’s a disorder in the same way being tall is a disorder in a world with only too-short doors. The population prevalence is around 10%. In evolutionary terms, anything that's that common can't be something that bad for your species.

What is ADHD?

My working definition is that ADHD is a primarily a context-dependent difference in how attention is allocated. It also has other emotional and behavioral consequences.

Kids with ADHD have trouble paying attention to things they find boring. However, they are exceptionally good at paying attention to things they find interesting. Those with ADHD like novelty (stuff that’s new or different) more than other kids. People with ADHD also tend to be good at tasks that require hyper-focus. This is zooming in with our attention on one particularly interesting thing. It’s a state of such focus that it leads to the exclusion of other input from our surroundings.

Evolutionary biology can help us think about why this is the case. It was good to have a few distractible hunters around. We were in tribes on the Serengeti. A few tribes-people poking around meant extra gazelles for dinner. While most individuals would be looking ahead at the main hunt, a few distractible outliers means everyone ate more at the meal. This is a life and death difference, and we are the result of how much better it was to have that variation in our ancestors.

In the context of having to sit in school—or worse, paying attention on Zoom—the same ability to be distractible becomes a disability. Imagine an allergy to boredom. Some people have just a little itch with their allergies. Some can die from abrupt and extreme anaphylaxis. ADHD is, in part, an allergy to things that are “boring” according to that person’s brain.

Just like allergies, the range of experience with ADHD is broad. Some people have just a touch of “the inattention.” Others will avoid tasks that require attention (e.g. tax preparation and editing this very substack for sentence structure) like a bee sting to the deathly allergic. People don’t get a list in advance of plausibly boring things and get to choose what they will hate. They don’t get to pick VERY ENGAGING. It’s just assigned to each person, thank to the fates. And they have to choose what to do with it. Like Stan Lee’s X-Men—mutants who had super powers and terrible curses—it is finding the right context and the right community that made being a creepy looking beast into a world saving super hero. So, too, ADHD is often about what you do with it. In summary, ADHD is a brain difference. Sometimes it's a problem. Sometimes we can help. There's nothing wrong with you, in the bad sense of the term “wrong.” Sometimes the environment and the person aren't the best fit. If we can help, there are benefits to doing so, and risks.

The Muir-Cox Criteria for ADHD

Lara Cox, M.D. is a remarkable physician—with whom I trained. She also has ADHD, and taught me a heck of a lot about it. Together, as a joke, we developed a set a four criteria that she believed were much faster screening questions for ADHD than a traditional symptoms of inattentive-type ADHD. In over 60,000+ hours of clinical practice, my experience has been that these questions are a reliable predictor of having all nine out of nine inattentive symptoms of ADHD as taken from the DSM-5.

The four questions are as follows:

What happens when you try to meditate?

Do you worry that you're lazy or dumb?

Do you procrastinate?

Are you less good at things than your level of smart would predict?

The questions aren't intended to be elegant. But there is a pattern of responses to them, which I will share now, which are the “positive” findings.

Q: What happens when you try to meditate?

A: Answers to this question are often “you're kidding right??” Or in the realm of incredulity that anybody could do any meditation. The ability to empty one's mind is some thing that is almost unimaginable to people with ADHD coming to see a psychiatrist, and so it's really the emotional reaction as to the impossibility of meditation that I'm looking for. It's worth noting that experienced meditators often grappled with these questions in meaningful ways, and so this is more of a question for general audiences.

Q: Do you worry you're lazy or dumb?

A: Self-reproach for not being good enough is often internalized by people with ADHD. Because it's not obvious to any of us what our brains are preventing us from doing, there are often important tasks that people with ADHD find themselves avoiding for unclear reasons so the default is to think one is lazy or dumb. This avoidance is what the question is getting at. And if you ask it this way, it often reveals itself under a layer of casual blame of the self.

Q: Do you procrastinate?

A: The answer to this is usually a shared laugh, based on what they've told me already. Procrastination, which is the “avoidance of tasks that require sustained mental effort” for “boring” things is a key feature of inattentive type ADHD. This is often a moment of humor in a psychiatric interview.

Q: Are you less good at things than your level of smartness would predict?

A: The speed with which this question is answered with a loud YES is what tends to stand out. It's phrased in this awkward way on purpose. This is so people will ask questions about what I mean. It’s also so awkward, in wording, that inattentive people will miss it. This is also diagnostic info for me, at 60K+ hours of pattern recognition asking the same questions.

It's often smart people who underperform. This is especially common in women. Because the hyperactive symptoms of ADHD are less common and girls and women, they don't cause trouble in the classroom early on. They are commonly “missed” when they are young girls when it comes to an ADHD diagnosis.

The under performance is due to the ADHD-unfriendly constraints—distractions, timed conditions—of what they had to complete in school or work.

It's a little bit like asking people about their beekeeping skills when they have a deathly allergy to bee stings. Those individuals are likely to underperform at beekeeping, no matter how good they have the potential to be at the basic bee-maintenance skills that go into it.

This is an approach for experts, and one that is intended to be lighthearted and make a clinical interview a little easier. That having been said, according to the American Academy of Family Practitioners, the evidence for rating scales and screening measures is bad—a “C” rating indicates that the evidence is not strong. It's an empirical question as to whether even goofy questions like the above are better or worse than our current standards2.

It’s Not Anxiety…Sometimes It’s ADHD.

ADHD can often feel like anxiety for people with ADHD, particularly when their energy levels are low, their attention spans are strained, and their environments are disorganized.

I will often ask my patients if they feel anxious coming home at the end of the day? I will then follow up with: “does it have to do with things like cluttered surfaces or a messy coffee table?”

My patients with ADHD will say, “Of course! I have to clean it off entirely.” The chaos on the coffee table is a reflection of the chaos in the person’s mind. The experience of the disorganization causes distress and agitation. I don’t understand this same brain circuity as “generalized anxiety disorder” or other anxiety disorders, although they can overlap.

What makes adult ADHD different from a generalized anxiety disorder is that it’s the clutter, chaos, and disorganization that gets in the way of focusing— not worrying about intrusive anxious thoughts about past performance or future woes.

The Process of ADHD Diagnosis and its Discontents.

ADHD is a condition that is currently diagnosed clinically. This means the diagnosis is based on history and examination, not neuropsychiatric testing.3

History is the story a patient tells you.

Examination: what clinicians observe while patients tell their story.

There is no definitive required testing to make an ADHD diagnosis! An ADHD diagnosis is made by a mental health professional with the expertise to navigate the process of a differential diagnosis. The role of neuropsychiatric testing is to answer questions that are not answerable from that history and examination. I can't tell, just by talking to someone, if they have a specific deficit in working memory, reading comprehension, or other measurable but subtle cognitive functions.

The question, in any diagnostic interview, is why. What is the best explanation for:

1. the story I've been told and

2. the observations I'm making?

People come to see me with complaints of inattention, underperformance, distress, or those problems along with their “presenting complaint.” Our task is trying to parse out why. Attention is a process that involves myriad brain networks. It’s complicated. We don’t want to mistake it for something else. Often, people have more than one DSM-defined problem. Difficulty paying attention may have to do with the fact that you're traumatized, depressed, or have ADHD, and sometimes all at the same time.

Not all inattention is ADHD, and not all ADHD is inattentive.

Do we need neuropsychologic testing?

Neuropsychologic testing is a lot like an EKG for a heart condition. You can tell with your stethoscope if a person has a heartbeat that's skipping, but you can't tell electrophysiologically why. So you get more testing. When it comes to ADHD this is called neuropsychologic testing. The difficulty is of course this testing is usually very expensive, often comes with long wait lists and takes a lot of time.

For my colleagues in industry, the ability to create more reliable diagnostic tools for ADHD would be a godsend. It's a complex condition, but we don't have the kind of biomarkers yet that we do for heart disease. It would be awesome if we could define digital phenotypes for ADHD and integrate those into our clinical and diagnostic digital toolkit. #FreeStartUpIdea.

What About Therapy?

Psychotherapy has been turned into the branded product: “Therapy” by venture backed companies. Just ask Michael Phelps:

It's not that simple. We have an evidence base for psychotherapies, plural, for a variety of well-defined conditions. Is there a specific therapeutic modality that is helpful for the underlying condition we are talking about?4

When it comes to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, I've got good news and I've got bad news about therapy. The bad news, first:

There is no standalone psychotherapy that is as broadly effective for ADHD as the medications on the market today. As covered in my prior articles, the most definitive RCT on this is the MTA study5, done at NYU among other sites. In this study, psychotherapy and methylphenidate were compared in children. The study was stopped early by the institutional review board. Methylphenidate, a kind of stimulant medication, was so much more effective than psychotherapy that it was considered unethical to continue to prescribe placebo to children and just give them therapy.

The good news is there is one specific therapy, organizational skills training6, or OST, which is effective for executive dysfunction and ADHD.

Here is the link to the manual on amazon. (affiliate link).

This therapy is not widely available, many therapists are not trained on it and I am highly skeptical any of those therapists are who you will match with on Talkspace.

People with ADHD often have other problems7, and therapy may be helpful for those other problems. Therapy can also be helpful to cope with or understand what it’s like to live with ADHD, especially if you have felt or been told you are stupid and/or lazy for much of your life. Psychotherapy is NOT an effective treatment for the core symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity.

One of the reasons ADHD is also so justly in the house of medicine, is that it requires parsing out other problems in the body that can be mistaken for ADHD. Here is a list of research-linked problems or conditions that can “mimic” ADHD, or make it worse:8

… and so much more. ADHD is a medical condition. It most commonly presents in childhood, but many people are not diagnosed then. The first line treatments are stimulant medications, but these aren’t right for everyone.

Differential diagnosis for kids with attention problem is complicated, and that's what requires the time. We don't have great tools to diagnose ADHD itself, but we have appropriate tools to diagnose all the other things that can be confused with it. And we should use them.

Promising novel treatments being researched include transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), recently FDA approved monarch eTNS device, and LSD derivatives, now in clinical trials, with Mind Medicine9 as the industry sponsor, and more. The next generation of treatments are exciting. They promise better efficacy and a lower side effect profile. And that's what we need.

Thinking About Treatment With Stimulant Medications?

Stimulant medications are a first-line treatment.

There are two major classes of stimulants, and these are amphetamine salts and methylphenidate. Adderall and Ritalin are two brand names of compounds developed in these two classes. Similar compounds that are legally still prescribed— but very rarely are chosen because of the higher risks— include dexedrine and methamphetamine. For very good reasons methamphetamine is not the kind of thing that is routinely prescribed for ADHD.

There are short acting stimulants, and there are long acting stimulants. There are a variety of different formulations of long acting stimulants.

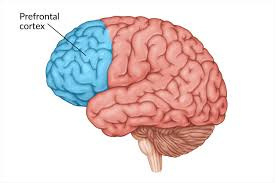

Stimulant medications work because they provide more dopamine in the prefrontal cortex (the part of the brain that does “wait, hold on one moment!” thinking…) as pictured here:

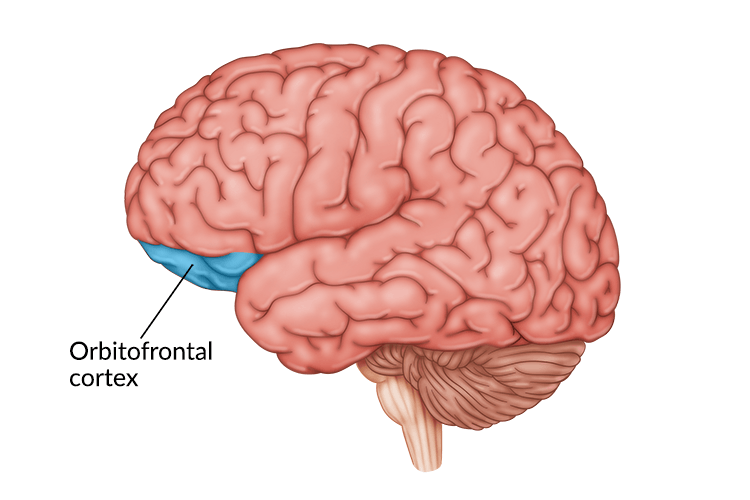

And more specifically, here:

Orbitofrontal= just above above the eyes!

That’s where the focus promoting effects of the medication are are acting. Since these drugs are blunt instruments when it comes to dopamine released, dopamine is also released in other pathways in the brain, including the nucleus accumbens (a tiny area pictured here):

…which is part of the reward circuitry of the brain. It is strongly implicated in addiction to the euphoric properties of stimulant medications.

In individuals with ADHD, they don’t actually get the same euphoric effect from dopamine increasing stimulants, or at least not at the dosages that we are using for treatment. They have a lower “dopaminergic tone” in their brain which certainly contributes to all that novelty seeking they are known for. The ADHD brain is less sensitive to dopamine—they don’t generally get the same “high” from the same dose of medication as a non-ADHD brain. Very strong biases in these data is that most of it is from college students, many of whom like to get high.

The reasons why prescription stimulants are misused are numerous and include achieving euphoria, and helping cope with stressful factors related to their educational environment. According to a survey of 334 ADHD-diagnosed college students taking prescription stimulants, 25% misused their own prescription medications to get “high” (Upadhyaya et al. 2005).

Given the rates of cannabis and alcohol use among college students to get high is around 50%, the above number is actually low compared to the base rate of getting high with other things.

Addiction is a real problem for some people and people with ADHD are suffering nonetheless. It deserves to be treated appropriately, and that means to not shy away from the most effective treatment that exists.

Broad Strokes, People: Benefits of Treatment of ADHD.

In people who don’t have ADHD, you get about a 30% performance boost from taking stimulant medication. People with ADHD, on the other hand, get a more significant boost in performance. It's a 17% boost an academic scores, which is between two and three letter grades better. It's a huge deal. These kinds of improvements change life trajectories. We base a lot of decisions at key moments in our development on the grades we got, and if you have ADHD, the data strongly supports the scores improving. This can be life-changing.

Stimulants are likely less addictive in people with ADHD if taken as prescribed, and more helpful in terms of improving performance, because they’re treating an underlying disorder, not just providing an “artificial” boost to performance. That artificial boost is real for others as well, but the risks and benefits don't have the same math.

People who are being treated for their ADHD are less likely to develop criminal behavior, which is a risk of untreated ADHD in youth. If you don’t believe me, go to literally any juvenile correction facility and spend 20 minutes there, and then tell me what you think. Or just read the following meta-analysis, and you'll see it's about 25% of that incarcerated youth.

It’s like the ICU for ADHD, but unfortunately, only after the justice system has taken a crack at ruining your future, and the future of your children.

Additionally, people with ADHD who have treatment are less likely to develop addiction as well. The fewer the ADHD symptoms someone is struggling with thanks to early treatment, the less likely they are to develop a substance use disorder. Paradoxically, oftentimes it is precisely these individuals who are most vulnerable to addiction who are turned away from getting this effective treatment or whose parents think it is contraindicated so never even explore the possibility.

Stimulants are remarkably effective. So is fire, both to keep you warm and burn down your house. We need to be careful, but we can't live in darkness.

Other Medication Options

Cochrane does reviews of the evidence across medicine. Thank God, says every doctor in training, for the Cochrane network’s meta-analyses. Now I have something to say on rounds when asked!

They reviewed alpha agonists—medications like clonidine and guanfacine— in ADHD. But, it’s been more than four years, so they pulled the publication. Can you tell we need more research?

A 2013 review, that hasn’t pulled for being too dated, stated the following:

Clonidine and guanfacine have been shown to be effective for the treatment of hyperactivity, impulsiveness, and inattention across several studies. After nearly three decades of experience with clonidine, its advantages and disadvantages are well known. While support remains sparse for immediate release guanfacine as an efficacious treatment for ADHD, substantial evidence demonstrates the efficacy of extended release guanfacine in the treatment of children with ADHD. In 2009, Intuniv® (guanfacine XR) was the first among alpha 2 agents to be FDA approved for use for treatment of ADHD in children and adolescents. In addition, a long-acting form of clonidine, a frequently used alpha 2 agonist, is in the process of being developed for use in ADHD.

For me, in 2023, the above still holds. We need more evidence and novel treatments, and as you can see above, they're coming, but the awareness of what already exists is also important.

Alpha-agonists are not as effective for inattention as stimulants. Not by a long shot. These are effective treatments and allow for lower cases of stimulant medication when prescribed alongside them in some cases, and should be considered more often. Specially in adults with hypertension, they do two good things for those individuals at once.

What about Strattera?

Atomoxetine is a non-stimulant medication, brand-name Strattera, that has decent evidence to support use in children when stimulants are not a good fit. There have been extensive reviews. However, it's data is relatively weak:

Cunill et al completed a systematic review and meta-analysis on twelve randomized, controlled trials (3,375 subjects) comparing ATX to placebo in adults with ADHD.38They calculated the standardized mean differences using clinician rated scales at −0.40 – a modest effect size. They noted that few subjects discontinued due to lack of efficacy (5% with ATX and 6% with placebo). However, a larger percentage of subjects discontinued because of adverse events (AEs) while taking ATX (13%) compared to 5% while on placebo. They concluded that the evidence to recommend ATX to treat ADHD in adults is weak because of the AE profile.

It works about half as well (0.4 vs 0.8-0.9 effect size) as stimulant medications. It’s not particularly tolerable for many.

As much as we want something that's not a controlled substance to be a great treatment for ADHD, I can't say that atomoxetine is that for most people.

In Summary: Medication Treatment (Benefits) for ADHD

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is real. It starts in childhood. It persists into adulthood. It's a fundamental and common difference in how brains function. Sometimes it's helpful, other times it's not.

The most effective treatments, stimulants, have significant risks and downsides. They also work well for some of the core symptoms. We can't be terrified of them just because they're controlled substances. The role of professionals, particularly those with significant expertise, is to educate, not just to prescribe.

Other treatments exist:

Strattera isn't very good in adults. If it works for you, great, but the odds are less that it will work for many adults than stimulants.

Clonidine and guanfacine are pretty good at dealing with hyperactivity/impulsivity and improving treatment with stimulant medications that can in turn be given at lower dosages.

ADHD interacts with a bunch of other conditions, and the medical assessment of people with ADHD is important, because attention is such a broad brain function. Problems with attention might be an underlying medical problem raising its hand and ask to be noticed. Physicians can take better care of our patients and ourselves if we pay attention to attention.

Treatment for co-occurring medical conditions is crucially important.

Screening for autoimmune conditions, sleep disorders, addictive disorders, post infectious cognitive impairment, malnutrition, should be part of any comprehensive medical evaluation for adult ADHD. It's not just a checklist of symptoms, it's an assessment of how someone's brain is working, and why.

Adverse Effects: Will Meds Kill My Kid?

I’m going to begin by reviewing the data on the long term risk of heart and cardiovascular disease. We have a recent large scale study:

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Medications and Long-Term Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases

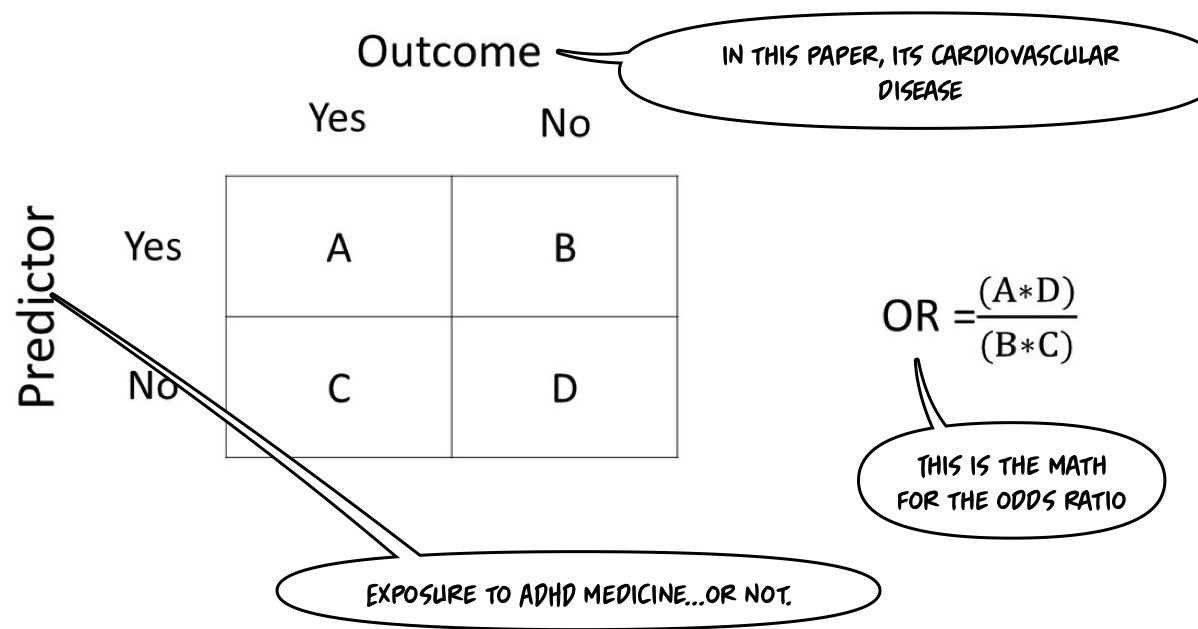

No matter what is demonstrated in the subsequent analysis, that title is Clickbait if I ever saw one! This is an article about risk. In epidemiology, we'll use the concept of an “odds ratio.” This paper is a “nested case-control” study design. It will be helpful to review basic observational study designs, at this point:

Cohort Studies involve following a group of individuals (the cohort) over time to observe outcomes. At the beginning of the study, participants are selected based on their exposure status (exposed vs. unexposed), and outcomes are compared between these groups. These are typically prospective in the time frame. They can also be retrospective if historical data are used.

In Case-Control Studies, on the other hand, participants are selected based on their outcome status (cases with the illness vs. controls without the illness). The study then looks backward to assess exposure status. They are Retrospective— authors know who got sick and who didn’t when they sit down to write the paper; what they are solving for is the degree of exposure.

This paper uses a Nested Case-Control design, a variation of a case-control study conducted within a defined cohort. Cases of a particular outcome are identified within the cohort, and for each case, a set of matched controls (who have not developed the outcome) is selected from the same cohort. This design allows adjustments to reduce the potential for selection bias since cases and controls are drawn from the same cohort.

The authors want to find out if more ADHD medicine leads to more cardiovascular diseases. However—diseases (plural) are not all the same.

Since we are following individuals after (variable) exposure over time but not randomizing them to one group or another, the study design cannot determine causality the same way randomized control trials can. However, when we're talking about risk to human health, it would be unethical to randomly assign people things that were understood to be risky to determine the risk. I’ve previously written about the lack of ethics in studies on parachutes vs. sham parachutes.

I quickly reviewed the math for odds ratios to find my readers the best graphic to illustrate the math.

This paper uses what they call adjusted odds ratios (AOR)—unless you're a more sophisticated statistician than myself, you have to trust that their adjustments are accurate. These adjustments are used to control for other variables, giving you a more accurate sense of the actual ratio that you could compare to other papers where the calculation was much less confounded.

The 30,000-foot view level result is as follows…

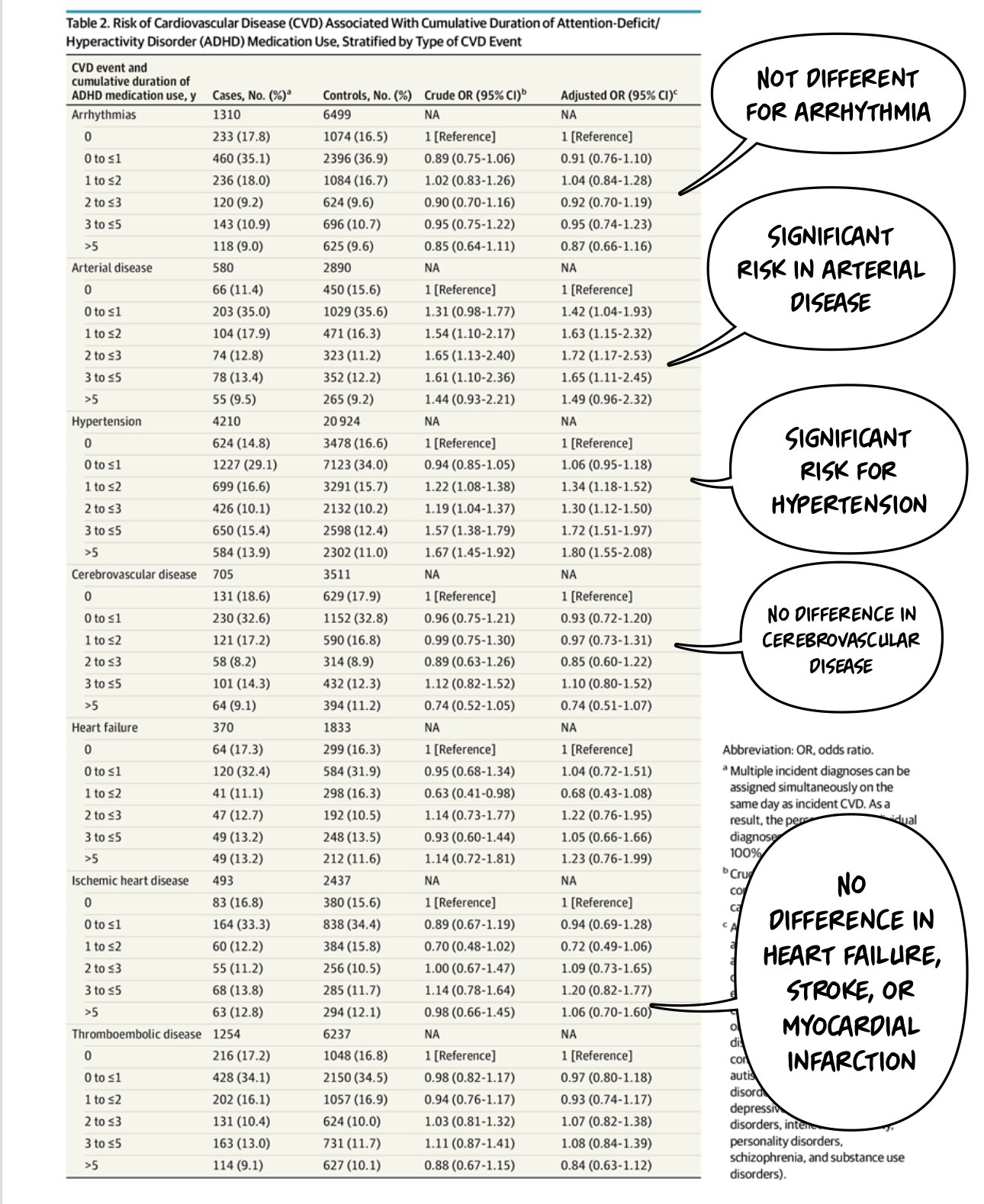

Findings In this case-control study of 278,027 individuals in Sweden aged 6 to 64years who had an incident ADHD diagnosis or ADHD medication dispensation, longer cumulative duration of ADHD medication use was associated with an increased risk of Cardiovascular Disease (CVD), particularly hypertension and arterial disease, compared with nonuse.

Well, that is quite a finding! However, it probably matters for us to work out “which ADHD medicine” and “how much exposure is safe?” along with “Is the risk different in children versus adults?” “Are all ADHD medicines the same, or are they different?” Let's break this down together! This will be fun!

In this kind of study, everybody has some degree of exposure. So, 100% of people in the study had a diagnosis of ADHD or a prescription for ADHD medicine, which they can track in their national scale database:

Baseline (i.e., cohort entry) was defined as the date of the incident with ADHD diagnosis or ADHD medication dispensation, whichever came first.

Who is in The Sample?

Design, Setting, and Participants This case-control study included individuals in Sweden aged 6 to 64 years who received an incident diagnosis of ADHD or ADHD medication dispensation between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2020. Data on ADHD and Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) diagnoses and ADHD medication dispensation were obtained from the Swedish National Inpatient Register and the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register, respectively.

What counted as cardiovascular disease ranged widely, in keeping with the different severity of hypertension compared to heart failure and heart attack:

Cases included individuals with ADHD and an incident CVD diagnosis (ischemic heart diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, hypertension, heart failure, arrhythmias, thromboembolic disease, arterial disease, and other forms of heart disease). Incidence density sampling was used to match cases with up to 5 controls without CVD based on age, sex, and calendar time. Cases and controls had the same duration of follow-up.

I hadn’t heard of incidence density sampling before, either. Here is a paper explaining its role in nested case-control studies if you are really, really interested. It is, apparently, “a very efficient approach to an epidemiological investigation.”

The age range is broad:

We conducted a nested case-control study of all individuals residing in Sweden aged 6 to 64 years who received an incident diagnosis of ADHD or ADHD medication dispensation between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2020.

And followed them till an endpoint occurred:

The cohort was followed until the case index date (i.e., the date of CVD diagnosis), death, migration, or the study end date (December 31, 2020), whichever came first.

The authors ruled out some individuals from the cohort they followed over time:

Individuals with ADHD medication prescriptions for indications other than ADHDand individuals who emigrated, died, or had a history of CVD before baseline were excluded from the study.

So, narcolepsy, binge eating disorder, Hypertension (clonidine!), and other conditions that will lead to the prescribing of ADHD medicine were not included. Neither were people who already had CVD or moved away so that we wouldn’t know the outcomes secondary to a deprived life (from a data standpoint) in a less epidemiologically sound country.

What Was The Exposure?

The authors were attempting to determine the relationship between “how much ADHD medicine exposure” and the bad outcome in question, CVD:

The main exposure was the cumulative duration of ADHD medication use, which included all ADHD medications approved in Sweden during the study period, including stimulants (methylphenidate, amphetamine, dexamphetamine, and lisdexamfetamine) as well as non-stimulants (atomoxetine and guanfacine).

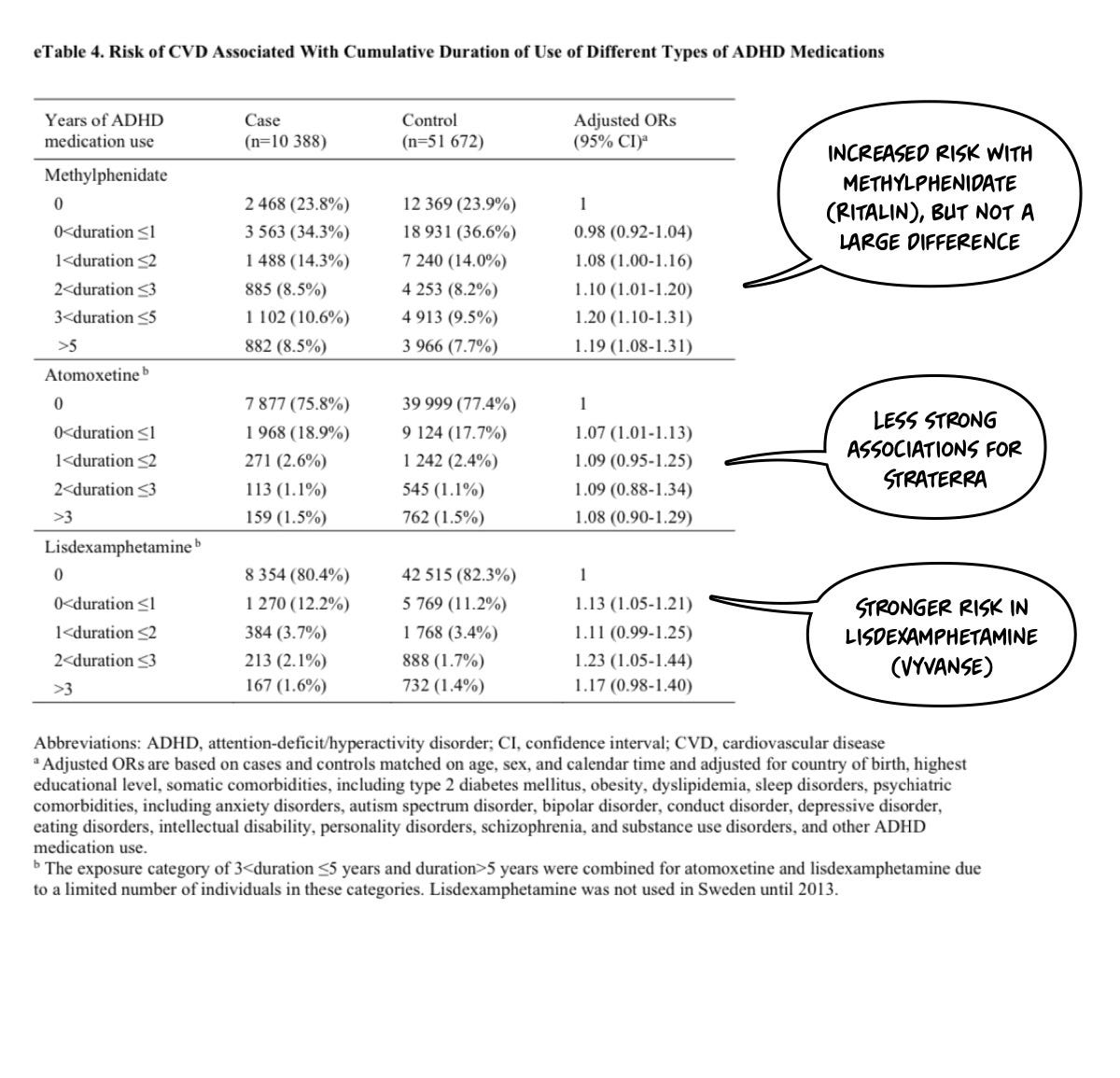

I’ll point out that I think this is a bad study design—a priori—because my pre-test suspicion is that neither guanfacine nor atomoxetine would increase blood pressure (for example). Thus, their inclusion will water down the results when lumped in. However, that is an empirical question that is only lightly addressed in the paper. You need to look at the supplemental materials:

What Was The Risk Profile?

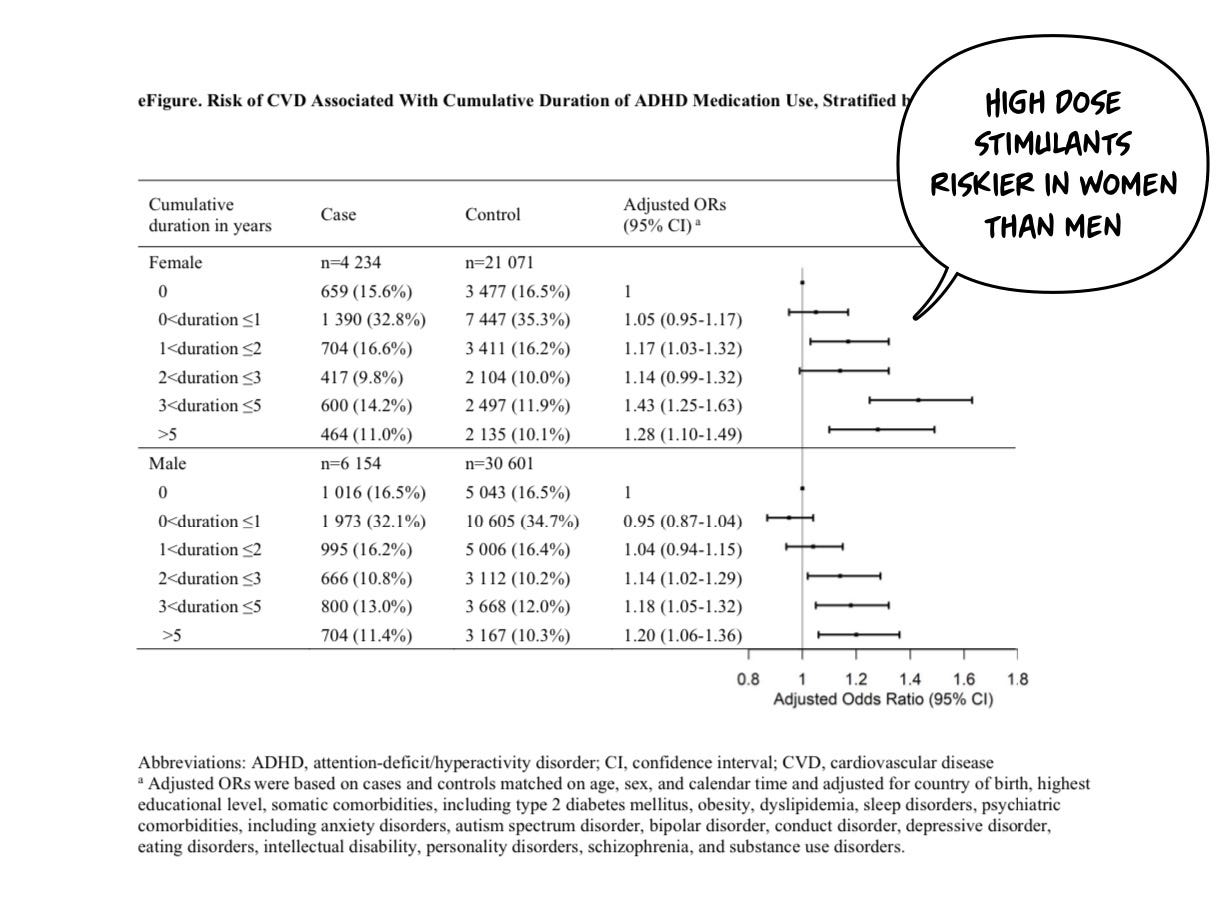

Higher risk was seen in women at longer exposure time frames:

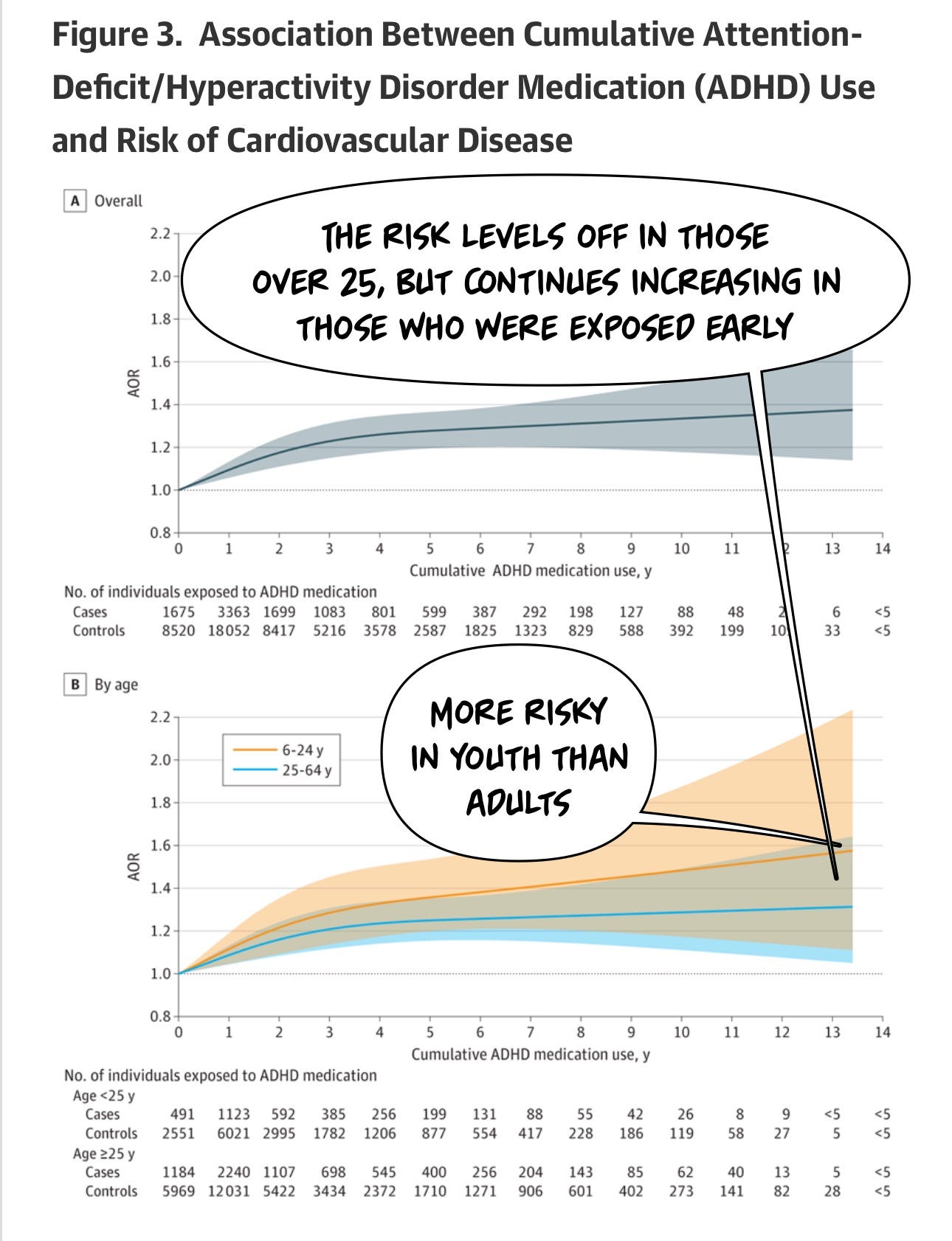

And youth evidence more risk (and more risk over time) than those over 25:

And the risk of CVD increases over time:

Across the 14-year follow-up, each 1-year increase of ADHD medication use was associated with a 4% increased risk of CVD (AOR, 1.04 [95% CI, 1.03-1.05]), with a larger increase in risk in the first 3 years of cumulative use (AOR, 1.08 [95% CI, 1.04-1.11]) and stable risk over the remaining follow-up. Similar patterns were observed in children and youth (aged <25 years) and adults (aged ≥25 years).

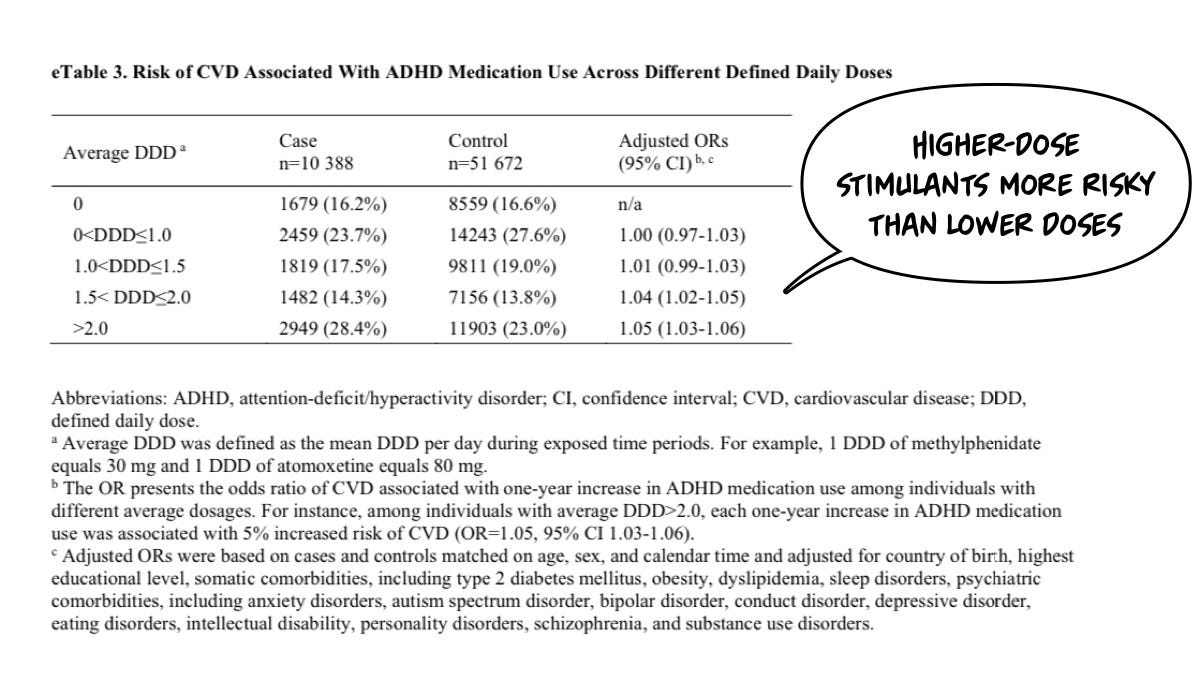

Additionally Higher risk stimulants were seen in higher doses.

Now, we should parse what we actually mean by “cardiovascular disease!” It’s not evenly distributed:

The actual rate of serious cardiovascular disease (heart failure, stroke, heart attack, arrhythmia) isn’t reliably higher. Arterial disease and hypertension did increase…by a little bit—in those exposed to stimulants for > 5 years up to 1.8x the risk of hypertension. However, hypertension alone doesn’t kill you. Strokes do. Heart attacks and Myocardial Infarctions do—and those aren’t reliably higher risk in this cohort.

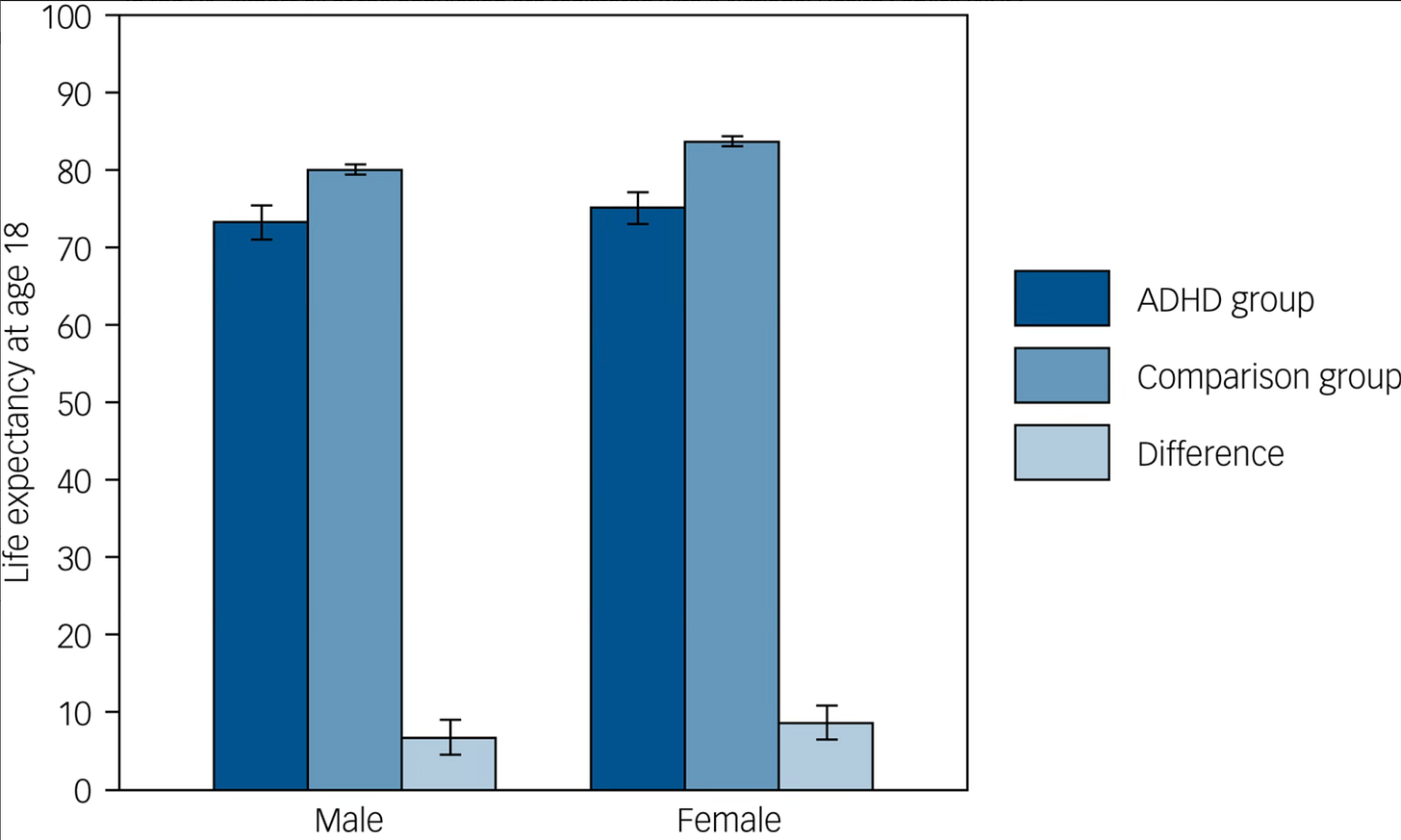

Many of the same authors examined the overall risk of death in ADHD in those treated vs. untreated in a subsequent paper…and found, despite the increased cardiovascular risk, the overall risk of death was…lower2!

RESULTS Of 148,578 individuals with ADHD (61 356 females [41.3%]), 84 204 (56.7%) initiated ADHD medication. The median age at diagnosis was 17.4 years (IQR, 11.6-29.1 years). The 2-year mortality risk was lower in the initiation treatment strategy group (39.1 per 10 000 individuals) than in the noninitiation treatment strategy group (48.1 per 10 000 individuals), with a risk difference of −8.9 per 10 000 individuals (95% CI, −17.3 to −0.6). ADHD medication initiation was associated with significantly lower rate of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 0.79; 95% CI, 0.70 to 0.88) and unnatural-cause mortality (2-year mortality risk, 25.9 per 10 000 individuals vs 33.3 per 10 000 individuals; risk difference, −7.4 per 10 000 individuals; 95% CI, −14.2 to −0.5; HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.66 to 0.86), but not natural-cause mortality (2-year mortality risk, 13.1 per 10 000 individuals vs 14.7 per 10 000 individuals; risk difference, −1.6 per 10 000 individuals; 95% CI, −6.4 to 3.2; HR, 0.86;

95% CI, 0.71 to 1.05).

Although ADHD treaments are associated with increased cardiovascular risk, they are at the same time associated with just south of 9 fewer deaths per 100,000 people than leaving ADHD untreated:

Individuals with ADHD are at risk of early death. The cardiovascular risks come later, and are not life threatening, over all.

In Summary: Cardiovascular Disease Risk?

Yes, your ADHD medication “might kill your kid” over the time scale of many, many years. But, it’s more likely your ADHD will kill your kid earlier on its own if left untreated. The deaths happen early, and the risks happen late.

If only there were non-medicaition treatments that worked and had lower risks? Oh, wait, there are…like the Monarch eTNS device we are thrilled to offer in my practice, Fermata.

Next, we will address…

Does ADHD increase All Cause Early Mortality?

—not just cardiovascular risk from a drug.

We have another extremely recent study…and this isn’t about the drugs, it’s just about ADHD itself.

Some of my most popular articles are about ADHD. This disorder has a storied history and has had several monikers over the years. In the earlier 20th century, we referred to it as minimal brain dysfunction. Subsequently, we had attention deficit disorder. Then, most recently, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder was added. This, in turn, has three identified subtypes: inattentive, hyperactive, and combined, where you have both hyperactivity and inattentive symptoms.

It's even gotten so popular that we have “made-up” diagnoses—essentially, individuals advocating for new diagnostic entities that are not yet in the pantheon of the International Classification of Disease (ICD) or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR); it's kind of like the farm leagues for diagnosis? But we have conceptualizations like “rejection sensitivity dysphoria” or RSD, as a maybe an ADHD subtype. We've got endless TikTok videos. We've got ads where people misspell things on purpose to lure in those with ADHD for some kind of scam.

A pedantic point: RESPONCE is not how you spell the word RESPONSE. My hunch is this is part of a scam sales funnel that selects for individuals who are paying no attention to the details. To be clear, is the claim that “hypersexuality is not infidelity [but instead part of ADHD]” factual? This is not a thing—except, perhaps, as clickbait.

While that is true about the medicines themselves, today’s publication in the British Medical Journal is an epidemiological study, following millions of people over about 20 years, evaluating the rate of early death in individuals diagnosed with ADHD.

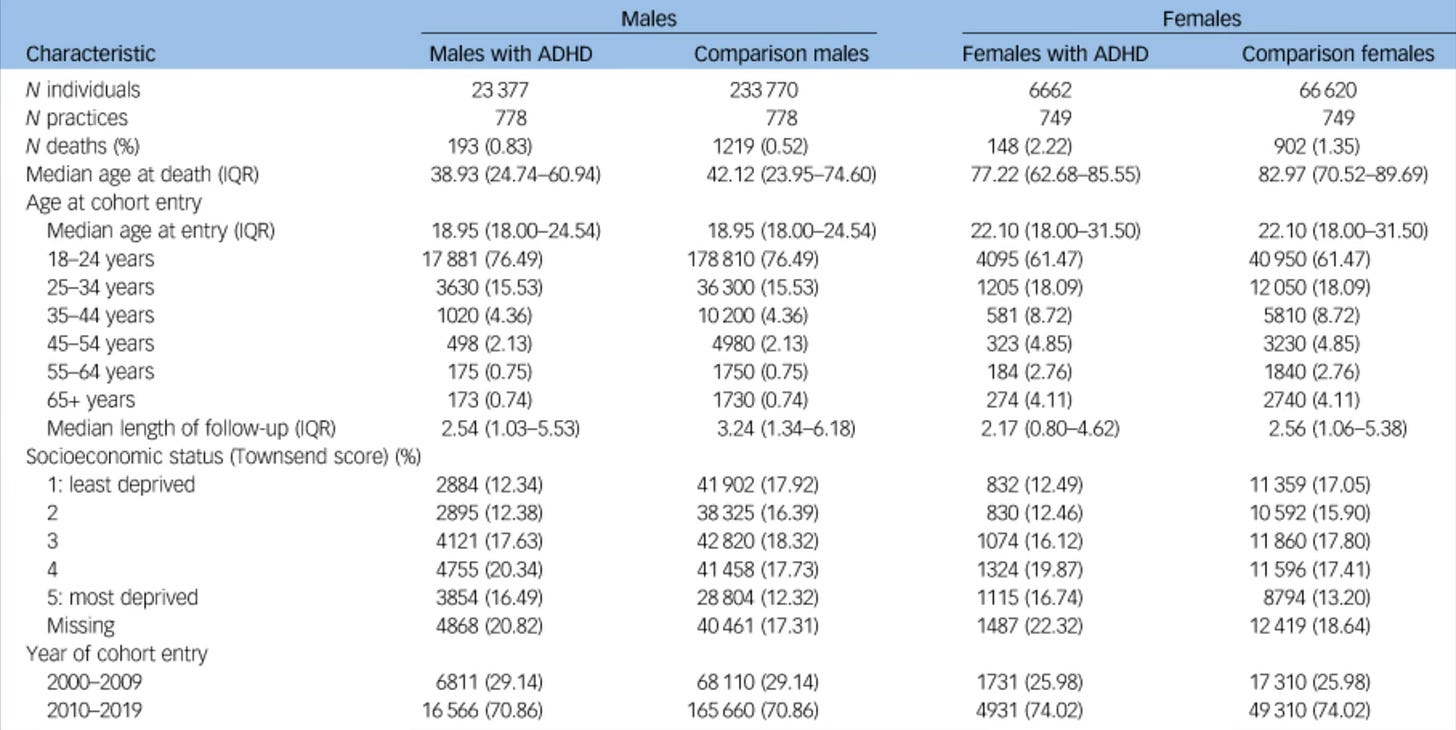

With any study, my first question is “Who is in the sample.” As I frequently joke, this newsletter could be renamed. “The Table One Star-Ledger.” The first table in an academic research paper in biomedical science, Table One, reviews the question of who is in the sample. Here, we find the following:

A matched cohort study using prospectively collected primary care data (792 general practices, 9 561 450 people contributing eligible person-time from 2000–2019). We identified 30 039 people aged 18+ with diagnosed ADHD, plus a comparison group of 300 390 participants matched (1:10) by age, sex, and primary care practice. We used Poisson regression to estimate age-specific mortality rates, and life tables to estimate life expectancy for people aged 18+ with diagnosed ADHD.1

If we dig in further, readers may ask, is there more we could understand? So glad you asked.

They matched 30,000 ADHD-diagnosed individuals with 300,000 participants who didn't have ADHD. The authors review, retrospectively, what occurred as time elapsed. My erudite review of cohort and case-control studies is available here. Allow me to save you heartache—this study design won’t tell us why people died early.

You will quickly see that the percentage of death was higher in the ADHD groups for both men and women —and quite a bit higher for women with ADHD.

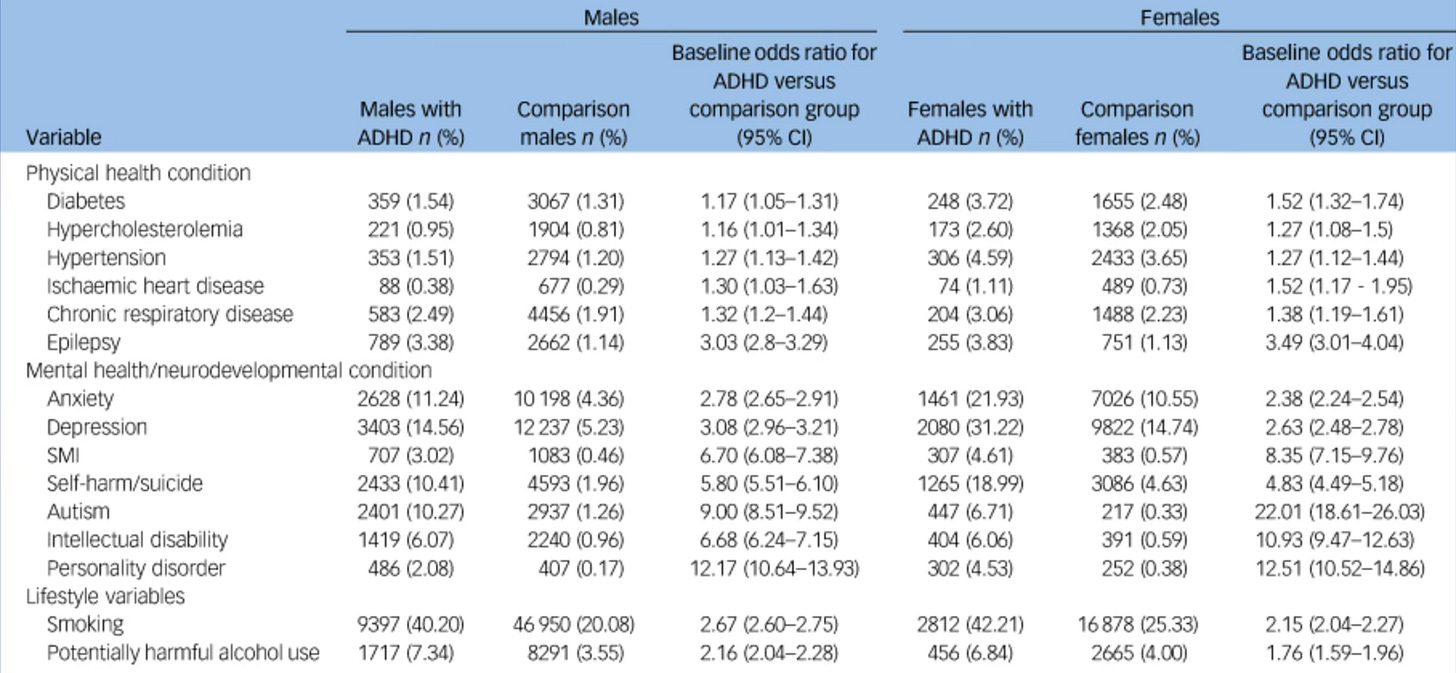

They then examined the rates of disorders that co-occurred with ADHD versus the matched population in over the time period in question:

We will notice in individuals with ADHD there are some significant differences in other problems they have. Smoking rates are vastly higher. Alcohol abuse is vastly higher, and there are significantly higher rates of suicide attempts by a factor of 10 times, and even personality disorders are orders of magnitude more prominent. It seems that people with ADHD have other problems. It's not hypercholesterolemia; although it is a bit more prominent, we have some real drivers of badness for a less long, healthy life.

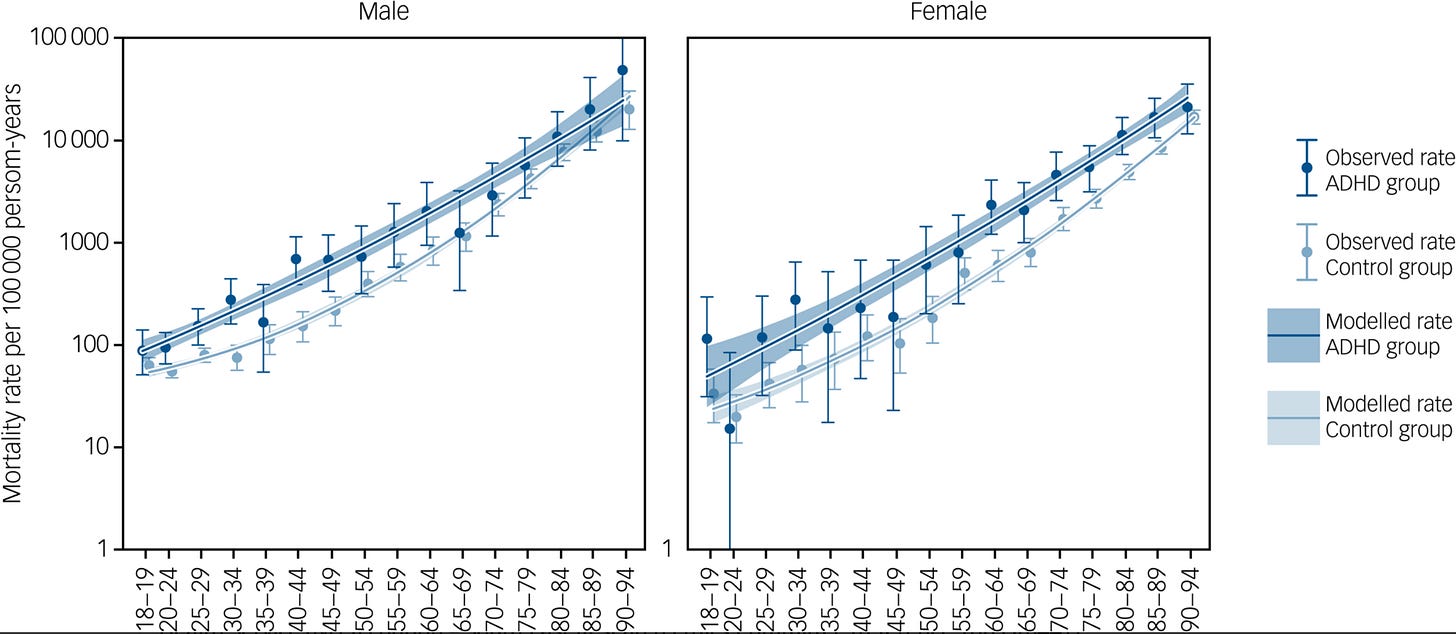

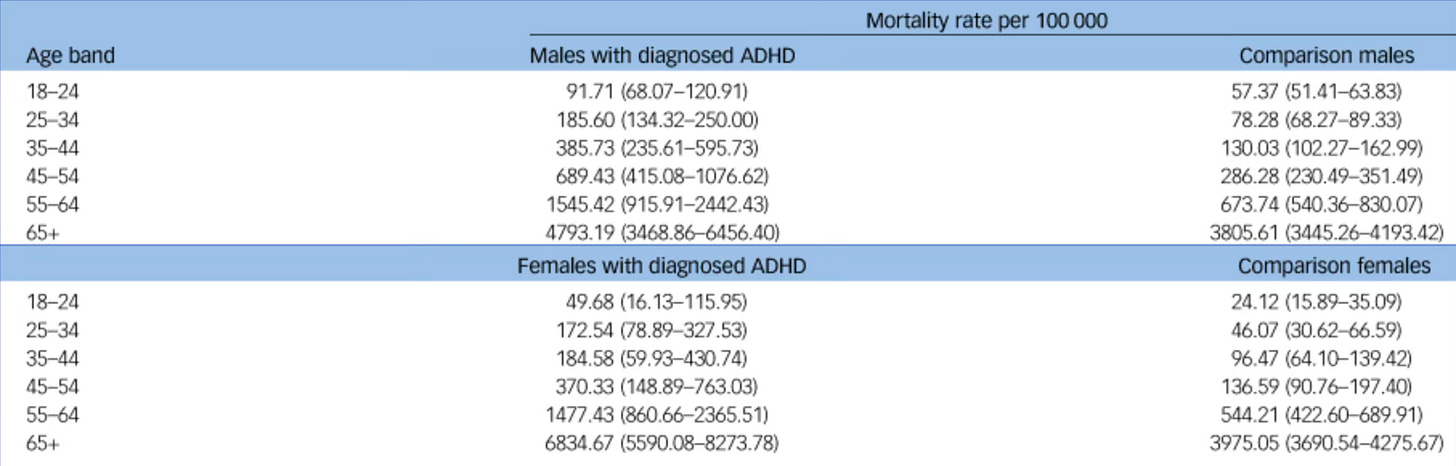

Thus, at almost every age group for men and at every age group for women, humans with ADHD are more likely to die and more likely to die younger:

ADHD predicted early death, among both men and women.

The apparent reduction in life expectancy for adults with diagnosed ADHD relative to the general population was 6.78 years (95% CI: 4.50 to 9.11) for males, and 8.64 years (95% CI: 6.55 to 10.91) for females.

These findings don’t tell us WHY people with ADHD are dying earlier. Cohort studies can’t demonstrate causality. They are hypothesis generating, only. However, the data make it clear that ADHD is a threat not only to quality of life, but to life itself, over a long enough time scale.

This is serious, impacts women more, and thus should be an area of ongoing and robust inquiry and public health focus. Let’s not let people die earlier than they need to—they have lives and families. We need to keep ADHDers around, healthy, and happy. I say this both as a physician and as someone who has ADHD that, I now know, predicts my early death. For my family too, I beg my colleagues—let’s focus on reducing the risks while ensuring long, healthy lives for all of us.

Given we are not sure why these early deaths occurred, perhaps we encourage ADHD sufferers to get all the close follow up to which they are other wise entitled. Get serious about alcohol use disorder, smoking cessation, and other preventable causes of death.

What to do with that grim data on Mortality?

You are planning on taking good care of your kid anyway? You are having this conversation with me right now? Well, you have to keep doing that, and encourage the good “taking care of yourself” habits in your kid no matter what. Cause they have a problem that leads to early death—at 68, not 76—if people don’t take care of themselves. But those causes of early death are all preventable. So lean in on prevention for your child. You child is not a “child in the aggregate.” You can change the course of events by being a good parent.

What About That Monarch Thing You Mentioned?

We have had shortages of controlled substances, and it's made it difficult for people with ADHD to get their medicine. With all due apology to “as seen on TV products” to open jars:

If only there were a better way!

At least for ADHD, we have one answer. Stimulant medications are remarkably effective for treating some attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity. Limited data exist to support the benefit in executive function. Other medicines are less effective and have different side effect profiles. If only there were another way?!? What if I told you that it is FDA-cleared right now? What if I were to tell you it was not a controlled substance?

What if it wasn't a drug at all?

Well, would you pay 29.99? I’m just kidding; this is Healthcare. It will be more—around $1000-2000 for the device, and then about $250ish a month, but less than my Taltz medication.

Let me tell you about transcutaneous neural stimulation!

Remember TENS units? They create an electrical current, it tingles on your skin, and if you turn it up enough, it makes muscles contract. It was introduced as a massage tool and exercise adjunct on TV for your abdominal area for decades. At much lower power, it stimulates sensory nerves and does not cause facial contractions.

The Monarch eTNS Device!

The Monarch eTNS (external Trigeminal Nerve Stimulation) device is an innovative, non-invasive medical device that has been FDA-approved for the treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in children aged 7 to 12 years who are not currently on medication for the condition.

That is right—Monotherapy approval…instead of drugs. It’s by prescription only.

Developed by NeuroSigma, Inc., this technology aims to provide a safe and effective alternative to traditional pharmacological treatments for ADHD.

The Monarch eTNS system works by delivering mild electrical stimulation to the trigeminal nerve (Division V1), which is sensory innervation for the forehead. The device comprises a small, portable stimulator connected to a patch that sticks on your forehead. The electrical signals are transmitted through the patch, stimulating the trigeminal nerve. The device is worn in your sleep, and it’s an at-home treatment. I try mine tonight.

The device has an FDA clearance. The clinical trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of the Monarch eTNS device in reducing ADHD symptoms, such as inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. It has minimal side effects that are generally mild and short-lived, including skin irritation and mild headaches.

This should be a first-line treatment. If it works well for any individual child, it works better than any medication for any condition in all of psychiatry. It’s not a drug. It has very limited side effects. It is a revolution in ADHD for kids and another example of the Neuro-modulated future of our field. Kids deserve access to a more effective and safe treatment first.

The device, made by Neurosigma, looks like this when you wear it on your head:

It’s like a fancy TENS units you remember from 70s ads for nonsense abdominal fitness products. However, it’s way lower power—it creates an electrical current via sticky conductive pads on your forehead. You don’t turn it up much—just barely enough to feel a tingle.

The device pulses in a pattern which, via cranial nerve V division 1, resets your brain networks to be able to pay more attention.

YES, I KNOW.

IT IS SCIENCE! I am excited too.

How effective is Monarch eTNS?

In half of kids, it's twice as good as stimulant medications4.

If physicians prescribe this medical device, which is not a controlled substance, they may avoid stimulants in many cases.

The potency of the treatment’s description will allow me to use the Muir-Skee Low Emotionally Corrective Equation (M-SLo EQE). This allows us to convert an effect size of treatment into “difference in height” for easy and intuitive understanding.

The Monarch eTNS Device works exceptionally well in about half of kids. In the other half, it’s so-so. In the “super responders,” the effect size is 1.6. Stimulants are 0.8-0.9. This means if the device made you “a little bit taller,” using the M-SLo EQE, it would make you 4 inches taller. In the “average” case, it’s “only” 0.5 SMD effect size (about 1.25 inches). This is as potent as SSRIs in the first episode of depression.

More prescribing the Monarch eTNS device, pharmacists everywhere can be imagined to yell! It is possible to reduce hassle for ADHD treatment. Given stimulant shortages, the only real answer I can see is getting more effective treatments to more people—that don't require going through the DEA and supply chain constraints. This brain stimulator is the best treatment I've seen able to offer that at scale, and it’s available now.5 Move past stimulants? Onward to non-invasive brain stimulation!

Stimulants are a huge pain in the ass. Medical devices like Monarch are safer for ADHD. In the case of Monarch, it is “minimal risk!” One sleeps with a little pad on your head and the stimulator beside you. It is like a more comfortable CPAP device—for your attention.

What we prescribe first matters—because people stick with what works. Stimulant medications work. They also create a lot of extra work for physicians and stress for families! Every stimulant prescription—these days—means there will be a subsequent game of “find the pharmacy” to fill the script. Families are stalking pharmacies that legally can’t say what will be in stock, thanks to a settlement in the opioid lawsuits!

What does it cost?

The monarch device costs about $1000-2000 (the range is because there is an old version and a new version). The refills of the pads are the other expense— which is about $45/7 days. For kids 7-12, this can be covered with your insurance or a coupon for your insurance —if it's commercial. For adults, it's out of pocket.

For comparison, Mydayis (triphasic amphetamine) is around $400/month as its list price.

This is how we solve the ADHD treatment crisis—with better treatments!

I don't think we solve ADHD at scale by doing things that aren't scalable. At this point, there's a hard limit on stimulant medications, and there's a hard limit on the amount of frustration anybody is going to put up with to prescribe them.

Let’s prescribe the best treatment first—especially if it relieves hassle for health professionals and patients. And yes, I’d prescribe it for my kids too.

I enjoy a good conflict of interest disclosure, but I suspect conceptual and ideological disclosures matter a lot more when it comes to bias.

Efficacy and tolerability were first described in an 8-week, open-label, pilot study of eTNS treatment of 24 children diagnosed with ADHD aged 7-14 years1

Participants were assessed weekly with parent-and physician-completed measures of ADHD symptoms and executive functioning, treatment compliance, adverse events, and side effects.

After four weeks of nightly use, 64% of the study group were rated as “improved” or “improved very much” on the Clinical Global Impression–Improvement (CGI-I) scale.

After eight weeks, 71% had achieved that rating.

ADHD Rating Scale-IV (ADHD-RS-IV) scores showed a 47% decrease, compliance was 100%, and no child withdrew from the study due to adverse events

Wrapping It All Up

Your kids gonna be OK. That's the most likely outcome. I don't actually have a crystal ball, but I do have tens of thousands of hours of experience working with kids with exactly this kind of problem. We have the best treatments for the problem that you're telling me your kid has. These treatments are the most effective of any treatments we have in all psychiatry, there are risks to be managed, but that would be true whether your kid had this problem, or any other problem. We know what this problem is, and your kid has the problem that is the easiest to treat problem. That is the most responsive to treatment problem. It's like winning the problem lottery. Your kids probably gonna be OK. It's gonna be OK if they have to take a stimulant. That stimulant is probably gonna work. You may need to adjust the dose. They may need to go up, they may need to go down, they may need to switch the formula, they may need to combine it with another medicine, but eventually, when you get that dialed in, it's gonna be really helpful. Being a child Psychiatrist is a delight because I get to see kids do extremely well on treatment for ADHD, and that is a blessing for families.

And it makes me seem like a wizard, even though I'm just doing the most basic stuff that the large scale evidence suggests. It's very satisfying.

Your kid's gonna be OK, the treatment is highly likely to help, and if you stick with it, you're gonna be really happy that you did so.

And…so will your kid.

Thank you for reading, I hope it was helpful.

Phenomenal review, @Owen. It would be great if you could focus on the role of telehealth in the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD of children and adults, especially the latter. The recent CDC Report published in MMWR (before the MAHA folks shut it down) revealed that 46 percent of adults with ADHD used telehealth.services. We need to ensure that telehealth for diagnosing and treating ADHD in adults is here to stay. The restrictive DEA proposed Rules for telehealth prescribing of controlled substances, along with the MAHA Commission position on ADHD and psychiatric medications, would effectively shut down telehealth to treat ADHD. This would effectively deny millions of Americans with ADHD and related disorders from receiving the treatment they need.

By way of disclosure I’m a Stanford-trained Child & Adolescent Psychiatrist who is Chief Medical Officer of ADHDOnline/ Mentavi Health, a national telehealth company that offer both diagnostic and treatment services to people with a broad array of mental health conditions, including ADHD and related disorders. I’m also co-founder of Thynk, Inc. that has developed a brain-to-computer interface-driven video game, Skylar’s Run, to improve focus and attention.

I’ll say a few things about both companies. At Mentavi, we just completed a real world observational study to demonstrate that our asynchronous online diagnostic assessment is both valid and reliable in diagnosing ADHD in adults when compared to the current gold standard for diagnosing ADHD (which you point out), the clinical interview. The results of the study were published in a recent press release by Mentavi (Mentavi.com) which we are pretty damn proud of. This will hopefully move the field forward for both telehealth and diagnosis of ADHD in adults. We’re presenting the data at the upcoming World ADHD Congress in Prague in May. Co-authors include Steve Faraone, Jeff Newcorn and Andy Cutler. We will also publish the study in a peer-review journal. Folks can read the press release on our website.

Thynk, Inc’s Skylar’s Run video game has been in development for more than a decade. We have a slew of clinical data, especially studying Skylar’s Run for the treatment of ADHD in school-age children. Those studies showed consistent improvement in the core symptoms of ADHD as measured by the ADHD-RS. At one time we were going to seek FDA clearance, but we saw what happened to other companies that pursued this route, eg, AKILI’s EndeavorRx, and decided to commercialize our product for a broader range of health and wellness benefits. Recently we have been conducting small pilots at a large school district and a local YMCA and have demonstrated significant improvements in academic performance in many kids who play Skylar’s Run as measured pre and post by the subtests of both verbal and math fluency on the Woodcock-Johnson Test. This is obviously early data which we have replicated but blows us away to be able to demonstrate far transfer to improved academic achievement in as little as 5 weeks time. Neuroplasticity!! We’re also piloting Skylar’s Run with an adult population. We are currently manufacturing our first 1000 EEG headsets, so we are finally having a soft commercial launch! Folks can learn more about Thynk and Skylar’s Run at Thynk.com.

Lots of excitement in the ADHD space for both children and adults. As you indicated, ADHD can be effectively treated. We need more options, including non-pharmacological ones. I am really excited about the future and innovation in this space.

Great overview here. I didn't know about the Monarch device, excited to read more about it.