Mothers Of Adult Children

The vast majority of most parenting happens with adult children

It's Mother's Day. Yes, I already called my mother. Vita West Muir is my mom, and she is both a recurring character on this newsletter and podcast…and behind the scenes has helped me with some of the more ambitious pieces. Vita was a professional medical editor earlier in her life and still does some copy editing for major works of mine, Including my book: Adolescent Suicide and Self-Injury. (affiliate link).

Today, in honor of Mother’s Day, a meditation on the relationship between Mothers and their Adult Children.

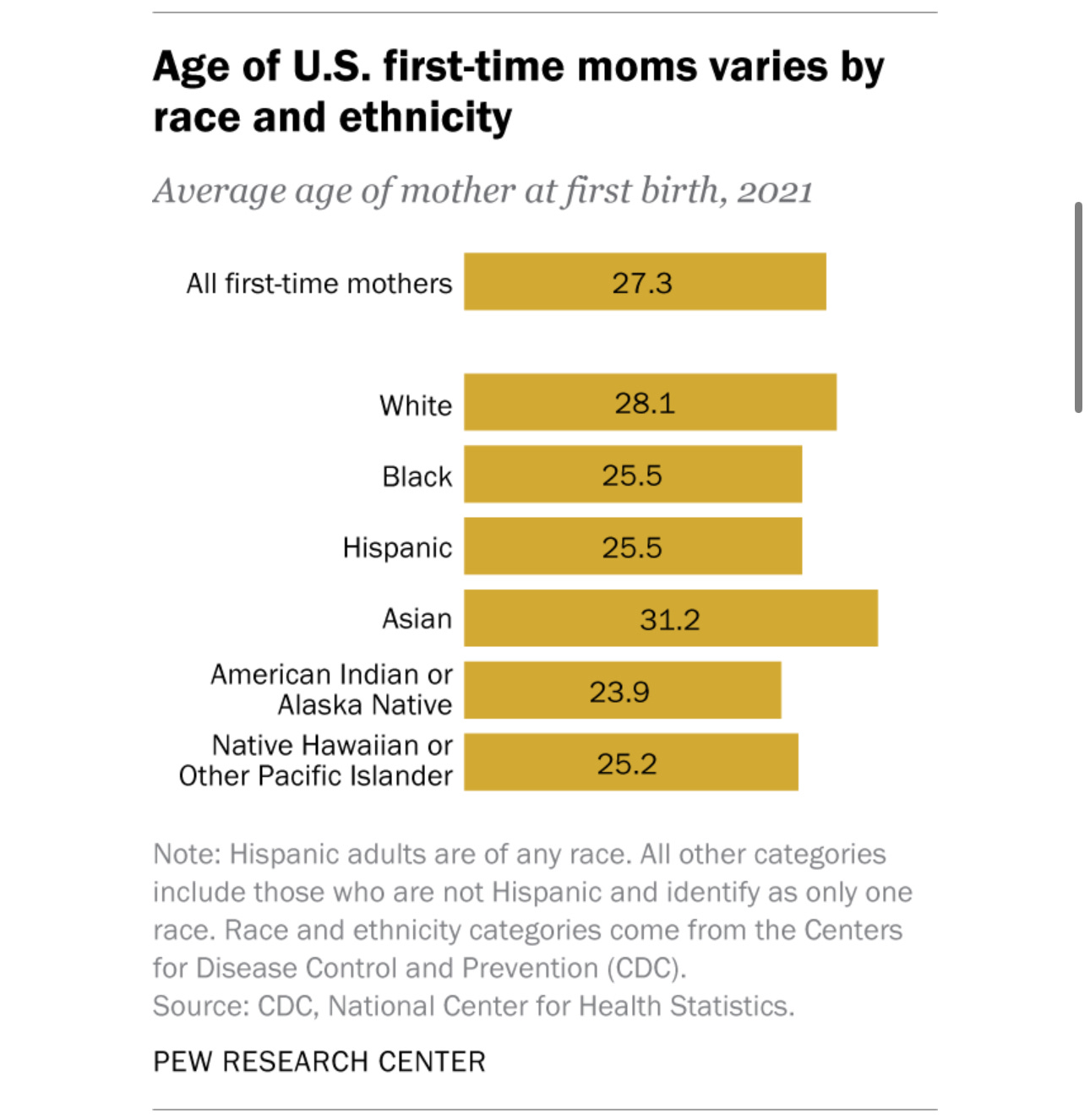

I will define adults as those 18 and over… The average age of first child in the US varies across ethnic groups, according to Pew:

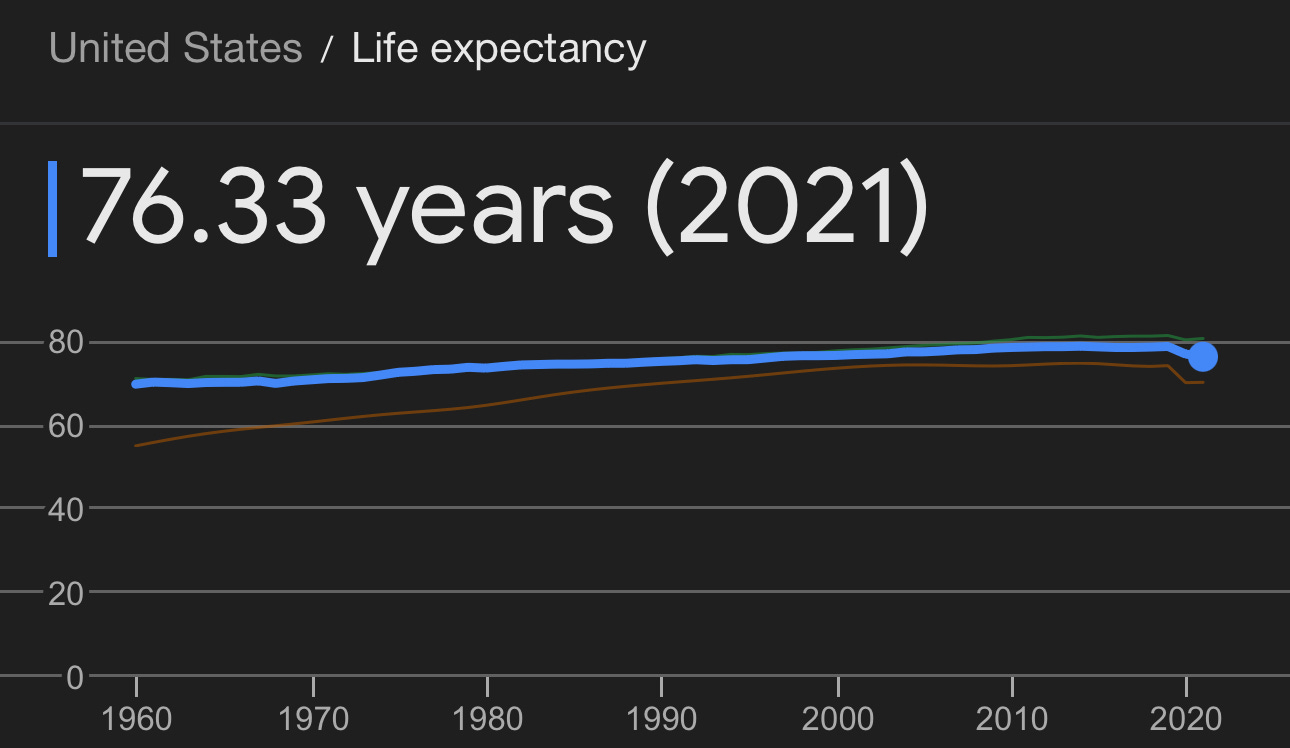

Across all moms, it is just north of 27. Add 18 years to this, and you have 45. What is the average life expectancy for women?

That leaves 31 years spent on earth as the parent of an adult child, which is just under twice as much time as mothers and children spend together before they can both vote.

The vast majority of mothering and having a mom occurs between adults. Raising children is neither easy nor fun. We spent a lot of time thinking about the role of mothers in early childhood because, of course, we do. Children are adorable, and also if you don't care for them, they can die. Parenting is a lot of drudgery and some moments of utter terror. There is joy and playfulness, but there are precious few activities that anyone would sign up for in advance that have the ratio of difficulty to satisfaction that motherhood features.

Little time is spent on how to stick the landing on the mothering relationship with adults who happen to be your children. These relationships are fraught. I will use my mother as an example because I'm familiar with some of the details. She also stands out because, as I have written, she was legally in the strange circumstance of adopting a 21-year-old child. In practicality, Alison had been her daughter since she was 12 years old. I have also written about my older sister, Alison, previously.

Being given up for adoption is one of the few moments where the distinction between being a biological mother and being a mom can be disambiguated: biological mothers’ birth children. Usually, this means you're stuck with your kid. Sometimes, mothers choose to give up a child for adoption. This is the maternal equivalent of a monarch's abdication of the throne. It is not undertaken lightly.

My sister, Alison, wasn’t given up for adoption per se—her biological mother simply didn’t care enough to bother being a mom. Vita, who had married my Art Muir, waited patiently to adopt her. I'm not trying to lionize my mother. At least, not more than she deserves. I'm trying to point out that there are choice points in some of our lives. Those moments might not exist in the lives of others. We're not asked uniformly to re-affirm our parenting status at some arbitrary point. Parenting isn't like Logan's Run, which expires at 18 unless you make a dramatic choice. The relationship between a mother and her children is a shotgun wedding—with fate as the officiant. Most people don't give up their children for adoption. Very few do. My dad was 46 when I was born. My mother was 36. Allison was 12 at the time. I was born in the vanguard of Dr. Silber’s vasectomy-reversal revolution. I was a miracle of science. My mother was married once previously, and so was my father. She had no children. My father had two, Alison among them.

My parents desperately wanted to have children together. This biological drive is potent. But being a mom, the kind of people we celebrate on Mother's Day, that's a choice. You can be a biological mother and be given the option, even at the moment of the birth of your child, to abdicate your role. Mother's Day is not about biology—it celebrates a fraught role.

My parents chose to undergo experimental surgery on my dad to make your author possible. But they made another choice, together, to raise to adulthood—and love— Alison. A child they did not create together. And yet, my mom chose to be a mother.

Alison would have many years of very serious health problems, some of which involved addiction. She went to work for Les Wexner, the former CEO of Victoria's Secret, and, reportedly, one of the individuals involved with the activities of Jeffrey Epstein. Yes, the dead pedophile pimp (from the Columbus Dispatch):

Their relationship was so tight that Wexner granted Epstein power of attorney that gave Epstein wide latitude to act on Wexner's behalf, and, at one point, Wexner was Epstein's only known client.

I don't know if Les was an Epstein client in the pedophile sense, but I do know that he was, per my sister’s report, a pretty awful boss. She told me about getting a job as a personal chef for a wealthy person. This turned into catering massive meals for 75 - 200 diners— alone. Being a chef is physically demanding, and trying to cook meals for dozens to hundreds of people requires a lot of time on your feet. My sister developed a degenerative disc disease and ended up getting spinal surgery. She remained on opiate pain medication for the rest of her life. She tried to get off. She could not.

For a mother, watching her child struggle with addiction and pain was torture. It turns out that it doesn't matter whether that pain and suffering is about your biological child. It's about whether you're the mother of that child. The age doesn't matter. Being a mother, in the sense of Mother's Day, the day when we celebrate moms, is like signing up for the military—you are agreeing to tremendous heartbreak, even if that's not the first thing that comes to mind.

I have friends who served in the military, and the rate of death by suicide is extremely high. Close relationships—people you would die for—this is what you build as a member of the military with your brothers, and it's what almost every mother feels for their children. It doesn't end when your children turn 18.

Alison struggled. I remember more than one holiday ended with a trip to the emergency room to discover what the hell had happened. There was the time she burned down her apartment by leaving a shoe on the stove. There was a time when her cognitive exam—in the hospital— was so poor that we thought she might have early dementia. We often got phone calls, as I sat next to my mother, in the car, or at the kitchen table, where she had to answer “Yes, Alison Muir is my daughter…we will be right there.”

Your adult children are the difference between living a life of joy and living a life of constant, grinding, nagging sorrow. No matter how successful you are? Your adult child, who is suffering, struggling, and even slowly dying? Your joy will be drained. Suffering by your adult children is the anchor heavier than the ship.

We often think of mothers as protecting their young, and they do. When they're young. In humans, your ability to protect your children expires long before your desire to keep them protected. It is the most fiendish of mothers, who are indifferent to the suffering of their children, and the most reprehensible who hurt their children. Even being indifferent to the suffering of your child? That's a new story. We vilify mothers who get this part wrong. And, to their credit, most of them don't. Most mothers behave in a way that is, in the context of the military, grounds for the metal of freedom. This is considered par for the course in motherhood.

My mom took care of Alison to the best of her ability until the end of her life and, honestly, a little bit after that. She made difficult choices, gracious choices.

What is striking about my mom's journey as a mother with Alison? There was a choice. She didn't have to become Alison's mother. You don't need to adopt a 21-year-old—who's got at least one parent, Dad, to whom you happened to be married. She could've remained “Vita.” You know, Dad's new wife. She made a different choice. This choice meant the world to Alison.

Most mothers don't have this choice point thrust upon them. It doesn't make their behavior towards their children, particularly in adulthood, any less virtuous. Endless mothers spend the childhood of their children, biological or adopted, sacrificing their time, love, energy, and work for the betterment of those children. And then, in adulthood, they look on, hoping, praying, advocating, sometimes helicoptering! Mothers are assigned to this unimaginably heavy role—mom. Mother is often the most important person in your life. I'm a dad. I am not the most important parent to my children. I wouldn't even wish I was—it’s a lot of weight. My daughter tells me this all the time. She's 8, and she loves Princess Mommy. Fathers are crucial, but we don't have the same central role in most children's lives.

Mother may be the most important person in the world to your child. In exchange, moms play blackjack with their happiness and satisfaction while risking endless heartbreak. Mothers who accept this mantle deserve to be celebrated.

Acknowledgment: I'd like to thank Vita West Muir for helping edit this piece of writing.