My readers are well aware there is a youth mental health crisis. The rate of suicidal behavior in young people in 2023 was 13% for high school girls and 7% for high school-age boys. We've been at a loss for data that supports effective interventions, and this has led to a tremendous amount of fretting, hand waving, thumb twiddling, and talking about how mental health is so important. What's more important than talking about how important something is is having an intervention to meaningfully modify the bad outcome in a direction that is favorable.

Oral medications for depression? Although there is no good evidence that they increase the rate of death by suicide, poor data led to a black box warning from the FDA on increased suicidal behavior in youth across all oral medicines.

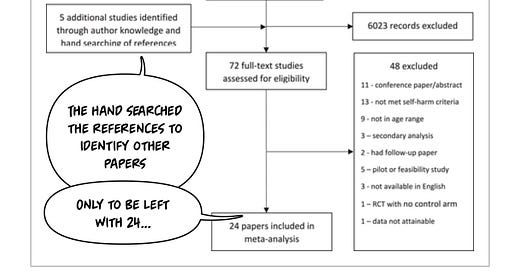

Similarly, I've written a great length about psychiatric hospitalization, which physicians often use to ensure “safety.” It doesn't work. I've looked, long and hard, to find any data that supports the use …