This is a narrative medicine piece, about the how and why of the stories we tell ourselves, no matter how implausible. Given the recent positive trial of transcranial magnetic stimulation for post-stroke rehab published in Neurology, this classic article seemed particularly fitting to re-share with my audience, much larger now than it was when this was first published.

New York’s Center for Hospital Care, or NYCHC, is a fictitious hospital. Medical school in America takes four years. The fourth year is a strange one. In the first and second year, in most schools, in keeping with the Flexner Report from over 100 years ago— which continues to circumscribe modern medical education—you learn basic science. There is a lot of basic science to learn. You spend some time in outpatient medical offices with primary care doctors. It’s there you get exposure to real patients and practicing doctor stuff. You don’t have any actual responsibility. It’s supposed to feel like responsibility, but somebody else always has their hand on the wheel.

The third year of medical school is also kabuki theater. You act as if you have responsibility. Every once in a while, by accident, you may be responsible for something. But the first time you get really close to actual serious responsibility, the kind of responsibility that you’ll have in your first year of residency training, referred to as internship, is in the fourth year. This is when young medical students, or old medical students, as was the case with me, audition.

Sub-internships, or Sub-Is for short, are month long rotations where you pretend to be an intern. And you might be given some responsibility. You will definitely be judged.

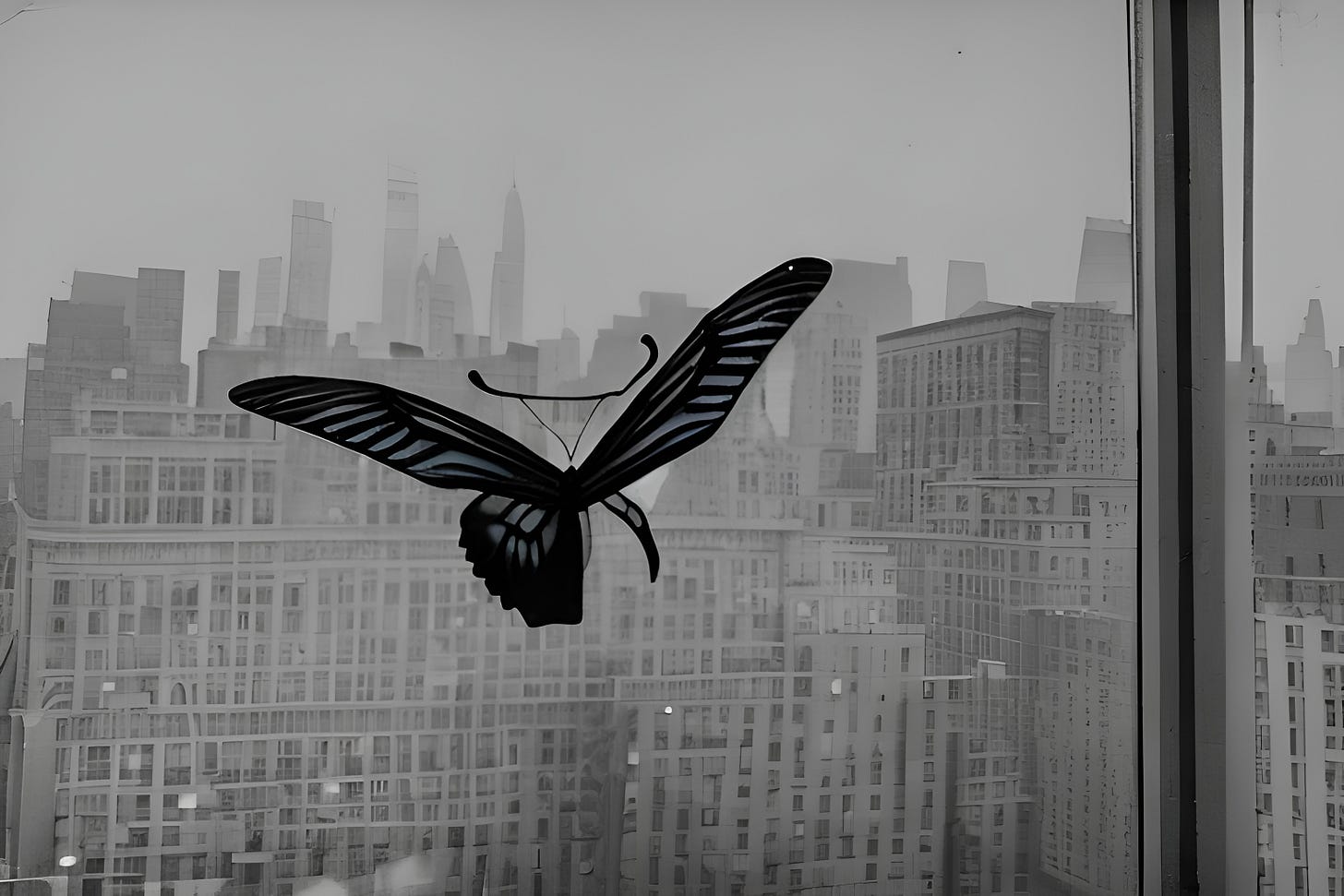

One of the issues in the US healthcare system is that the number of residency training spots, without which you can’t practice as a doctor, are fixed in number by the federal government. Since 1997. They are funded by Medicare. Residents are physicians. They generate billing for hospitals. They are a butterfly that’s only halfway out of the chrysalis, and you can imagine how awkward that would be for a butterfly. No crawling around like a caterpillar, and no flying around like a butterfly, just this awkward flopping escape from one thing as the metamorphosis takes its course. It’s this, but generating billable notes.

My sub-internship, my audition, it was at NYCHC.

Sometimes, in the middle of pretending, something real happens. Abraham Lincoln was shot with a real gun in the middle of a play. Alec Baldwin, tragically, accidentally shot someone on set. At NYCHC, I had a very real encounter with a very strange neurological condition.

The 7th floor of the hospital was being remodeled. It didn’t need to be, really. But plastic sheeting lined the halls in places, Sheetrock freshly up in others, and room 7045, with is silver-itself-got-sick colored numeric sign had a door slightly ajar. I pushed it fully open. It smelled like urine and chlorhexadine.

“I’ve been dead for some time” the gentleman said, reclining in his hospital bed, curiously casual.

There wasn’t a lot of affect in his tone. That’s the sort of thing you say if you’re learning how to do a mental status exam. The patient’s mood was whatever they said it was, but you put that in quotes. This person said “good”. So in the medical note that I was learning to write, I would write mood: “good.” Affect is how the person looks like they feel, it’s an observation. It’s supposed to be objective.

And, objectively, the person in front of me didn’t look upset.

The man just said he’s been dead for some time. I would expect that statement, from most people, to come with some distress, or confusion, or something.

Actually, no one would expect that to be said all. Axiomatically, dead people don’t say that. So it’s only the not dead who can say that they are dead, because dead men don’t talk.

Affect: congruent with stated mood. Stable. Euthymic.

“Hi there, I’m working with the consultation, liaison psychiatry service, my name is Owen Muir, and I’m not a doctor yet, I’m a medical student.”

I said, like they train us, the fact that I’m not a doctor. With 10 years of distance, it wasn’t really his confusion about my role on the team that was to be worried about. He thought he was dead. That’s a real problem. You know, in your brain.

“It’s nice to meet you.” he said, pleasantly.

“I’m a little confused, how long have you been dead?” I asked in an open ended way.

“Oh well now. A while. It must be a while.” The gentleman replied, with hestitation.

Two hours later, in a cramped hallway, which had a couple of computers on wheels, which had been recrhristened workstations on wheels, because someone was offended at one point in one hospital when somebody asks where the COW was. Computer on wheels. COW. And a patient got offended. So workstation on wheels or WOW, that is a solution to the problem of people with bad hearing and medical trauma. I was on the WOW. And I was looking up the Cotard delusion.

This vague response that I had heard earlier, and the rest of the conversation that followed, they fit in quite nicely with what I was reading. This was weird.

In what I consider to be a historical mistake, despite the joint status of the American Board of psychiatry and neurology, we decided to make those different medical specialties. Jules Cotard (1840-1889) was a neurologist, and Psychiatrist, when those professions were the same thing.

Dr. Cotard referred to "The Delirium of Negation" as a mental illness of varied severity.

Walking corpse syndrome, it’s other name, is a rare mental disorder in which the affected person holds the delusional belief that they are dead, do not exist, are putrefying, or have lost their blood or internal organs. Statistical analysis of a hundred-patient cohort indicated that denial of self-existence is present in 45% of the cases of Cotard's syndrome; the other 55% of the patients presented with delusions of immortality.

This didn’t make it into the DSM-5. So it’s not one of the first things you learn about. But it’s really specific, and it’s really uncommon, and it’s really weird, and the gentleman I just met proved me it’s definitely a thing.

It’s almost always the case that a person with the Cotard delusion has had an injury in the brain. That injury is usually a stroke. A stroke is when a blood clot gets lodged in a blood vessel, and that causes part of the brain to die, because blood can’t get to it. The brain needs blood. It needs the oxygen. It is really bad to have the brain be deprived of blood. We referred to this deprivation of oxygenated blood as an infarction. It’s the same infarction that we talk about in myocardial infarctions, or heart attacks, a more general term. In the brain, we call this a stroke. Medicine can be confusing.

But thinking you’re dead, insisting you’re dead, nothing being able to convince you that you’re not dead, that’s pretty confusing as well. It kind of doesn’t matter what you call it.

“How can you be dead? You don’t know you’re talking to me?”

“Yes, of course I’m talking to you”

“And dead people don’t generally have conversations with medical students?”

“That is true”

“Then how are you talking to me?”

“By answering your questions” he said.

“Dead people don’t get up and talk, usually”

“Well, there was that one guy, what’s his name?”

“Do you mean …Jesus?”

“Yeah, Jesus, he rose from the dead. It’s happened before.”

Socioculturally, my patient with the Cotard Delusion had a point.

He also had a series of small strokes throughout a deep region of his brain. These are called lacunar infarcts. There’s that infarction word again. A lot of really important brain occupies a very small area of space. The deeper you get in the brain, and the further back in the skull towards the neck, the closer to the brainstem, the more ancient the brain structures, and the more crucial they are to hold our shit together.

When these structures go, because they are cut off from blood, they die very quickly, and if the cortex is still there, it’s the storytelling stuff. It’s the part of our brain that puts things together. And it has to make sense of what’s happening, but not in a way that actually makes any sense. It just has to tell a story. The cortex, it’s tasked with “ higher order” issues than quotidian breathing or making sure our eyes track together. That “higher order” task is storytelling.

We are our own audience. The story, it don’t have to make sense. The secret sauce, the reason our brains are so believable to themselves, is that we automatically believe the stories we tell ourselves.

There wasn’t any reasoning, I was going to do with this gentleman, who had a brain that, on a brain scan, showed four or five small areas of dead brain, thanks to strokes that had happened both in the past and some more recently.

He had a heart condition. His heart condition is called atrial fibrillation. He also had a hole in his heart. We’re all born with a hole in our heart. A few have that hole stay open. This man had a shortcut from one side of the heart to the other. Through that shortcut passed the clot that formed when his heart didn’t contract like it was supposed to.

The heart muscle of the top of the heart, the atrium, it was basically wiggling, not contracting in an organized way. That led to blood sitting there for a little longer than it was supposed to. A clot formed in this static blood. Some of that clot flew through this hole. This foramen became a wormhole that let a clot bypass from one side of the heart to the other.

This little hole in his heart, it led to a hole in his brain. And that tiny hole in his brain, along with the other small holes in his brain, caused by prior clots, killing this area or that, it all lead to our strange conversation between the living and the not quite dead.

It led to a hole in his reality. He was dead. That was the story his cortex was telling him. It was utterly unbelievable. He couldn’t tell himself otherwise. He couldn’t tell a medical student otherwise. And he wasn’t alone in having this problem.